Max Liebster - Crucible of Terror

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Max Liebster - Crucible of Terror» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Crucible of Terror

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crucible of Terror: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Crucible of Terror»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Crucible of Terror — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Crucible of Terror», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Shop signs saying “German store”

are a true blessing...

Here [a German man] can be sure that

he has not given his

hard-earned savings to the

enemy of all that is German, the Jew...

A true German will shop only in German stores!

—“Viernheim People’s Daily,” December 10, 1934

Most of the townspeople received their pay on Saturday. So they would often ask us to come by on Sunday to pick up a small payment toward their bill. The Oppenheimers extended credit without charging interest, but a few customers even exploited that generous arrangement by not paying their bills at all. Bookkeeping kept us busy in the evenings and on Sundays. I took pride in my work, even in little jobs like winding up the smallest bits of string, flattening boxes, and folding wrapping paper. The two brothers ran an efficient and orderly business, and they appreciated my diligence.

❖❖❖

Life with the Oppenheimers also introduced me to an entirely different way of Jewish life. There was hardly any evidence in the Oppenheimer home that its occupants were Jewish. To my surprise their mother did not light the two Sabbath candles on Friday evening, nor did pictures of Moses or Aaron hang on the wall. They didn’t have two sets of dishes—one for meat and one for dairy. Back at home, when a kitchen knife belonging to the meat set came in contact with dairy products, Father buried the defiled blade in the ground for seven days to purify it. The Oppenheimers may have eaten kosher food at home, but when we drove through the Odenwald Mountains, we would sometimes eat in restaurants where the smell of smoked ham was unmistakable and the patrons dined on platters of meat drenched in milk gravy.

The Oppenheimer store even stayed open on the Sabbath. After all, Saturday was payday—the best day for business. Besides, like every other business in town, the store had to close for all the Catholic holidays. How could they also afford to close for Jewish holidays like Rosh-Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) as well? Of course, they observed Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). But what a difference from the way we had celebrated it at home!

At my boyhood home, on this most holy of days, my family would fast from evening to evening and attend the special synagogue services, including the Kol Nidrei, the haunting melodic prayer annulling any rash vows made during the past year. Before asking forgiveness from God, we would ask forgiveness from one another. My family made extensive preparations before Yom Kippur. Father took a chicken by its legs, its wings beating the air. He swung it over his head and mine (since I was the only male child) and spoke some Hebrew words. Then he turned the bird over for the ritual slaughter. Yom Kippur begins in the evening. We all took a complete bath, which was quite an ordeal because we had to heat the water on the stove. Only then would we attend synagogue.

A few days after Yom Kippur comes the festival of Succoth, or booths. We would sit together in a booth that Father had erected in our garden. There we prayed and took our meals. In the evenings we could see the stars through the leafy branches overlaying the top of the booth. Grapes and fruit adorned its walls, an expression of thanksgiving for the year’s harvest. The frail covering of the booth reminded us of the tents in which our ancestors dwelt in the Sinai desert.

At the Oppenheimers’ there were no booths, no thanksgiving prayers, only business. Succoth was seldom mentioned, and Hanukkah never. Unlike some Jewish families in Viernheim who burned candles at their windows, the Oppenheimers’ windows remained dark.

I had at least expected to take part in the cleansing ritual for Pesach, the Passover, packing and carrying away all the khometz kitchenware—dishes, forks, and spoons that had had any contact with leaven. When I lived with my family, I used to heat the stove until it glowed red and chase after the smallest crumb of leavened bread. Only then could we bring the special Pesach utensils into the kitchen to be used during the week of unleavened bread. But the Oppenheimers never ritually cleansed their kitchen.

I missed my family and the festive Pesach atmosphere, with the decorated table glowing in the light of the menorah. But even more, I missed the seder, the Passover meal. Each of us would be seated at the table with his own Hagadah, the special Passover prayer book. Being the youngest male, I would ask the Four Questions, starting with, “What makes this night different from all other nights?” Father chanted the story from the Hagadah, explaining the liberation from bondage in Egypt. Upon the table were the Haroseth symbols: grated apples with cinnamon, its brownish color representing the clay the Israelites used to make their bricks, and ground horseradish, which made us all shed tears.

Next to the table, Mother prepared the seder bed. She spread a fine linen cover over the couch and placed a silk pillow at the head. We wrapped up some matzoh and filled a glass with red wine, just in case the Messiah arrived and wanted to partake of the meal. We left the wine and matzoh out during the whole week of unleavened bread. Thereafter, the matzoh would end up behind the picture of Moses. As a little boy, I would reach behind the picture and secretly nibble on the Messiah’s meal.

Unlike my parents, the Oppenheimers gave no thought to the coming of the Messiah. Their empty Pesach consisted only of unleavened bread and a token appearance at the synagogue. Even at Pesach the business had first place. Hugo and Julius claimed that honesty and hard work were worth just as much as the observance of religious tradition. By their fairness, they helped people weather the economic depression—surely this was a mitzvah, a good deed. As time passed, I began to share their zeal for the business.

❖❖❖

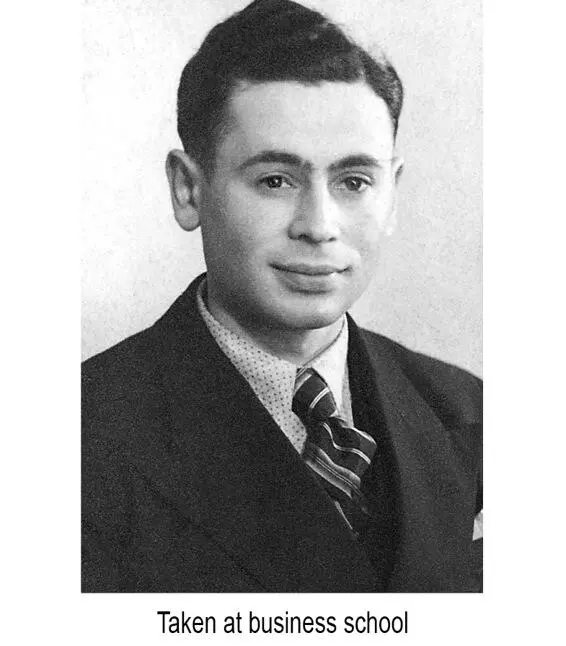

In 1929 just when I started to attend business school, the economy showed some signs of revival. It proved to be an illusion. The tidal wave that started with the crash on Wall Street swept mercilessly over Germany, plunging people into desperation. Julius even complained that I had become too expensive for them. The unemployed lined up restlessly each day to get their work certificates stamped so that they would be counted as needy.

By the time I finished my three years of schooling, the air was tense with fear and frustration. I could see it in our customers. In the streets, marching hordes followed behind their party flags shouting slogans. The workers and unemployed together vented their anger. When factions clashed, it was wise to get out of the way. Riots flared up all over the land.

It seemed ironic to me to see the very same people who clashed in the streets come together on Catholic holidays. They walked behind a cross held aloft by the priest. Arrayed in ceremonial garments, he led the procession out of town and into the fields, where he bestowed his blessing. The sight of carved images evoked in me a deep-seated repugnance. The Torah stated clearly: “You must not make for yourselves a carved image.” Truly I dwelt in an alien land!

On Easter night Catholic youth would set fire to

a pile of wood on the church square, and

after receiving the priest’s blessing

and being sprinkled with holy water,

they proceeded to march up to Jewish properties

with burning torches, yelling: “The Jew is dead!”

—Recollections of Viernheim resident Alfred Kaufmann

To my great surprise, when I graduated from business school, the Oppenheimers asked me to stay on as an employee—quite a respectable opportunity for a 17-year-old. It did not take long for the customers to ask to be served by “Mäx’che.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Crucible of Terror»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Crucible of Terror» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Crucible of Terror» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.