Max Liebster - Crucible of Terror

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Max Liebster - Crucible of Terror» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Crucible of Terror

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crucible of Terror: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Crucible of Terror»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Crucible of Terror — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Crucible of Terror», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The big day arrived. I felt nervous and excited at the same time. The rabbi came to our little synagogue. He gave a heartfelt welcome, stepped down from the platform, and sat among the men in the audience. My mother and sisters sat in the balcony, the place for the women. My heart pounded as I climbed the two steps and opened the little door of the engraved wooden barrier separating the Jewish congregation from the platform. Here in this special place, the holy writings were usually kept in a sculpted wooden closet, hidden from the view of the audience by a burgundy curtain. Awaiting me on a pulpit in the middle of the stage lay the Torah scroll, unrolled to reveal the portion of Scripture I would read. The holy scroll was bathed in the light of a candelabra with seven branches.

For days I had been dreading the sacred reading. Now my stomach was in knots, and my mouth felt like cotton. Behind me, I could feel the presence of the whole community. Like me, they either wore hats or yarmulkes, and some bore on their shoulders the Tallith, a blue-and-white-striped prayer shawl with silver seams and fringes. Some men would take the fringes, touch their personal prayer books, and kiss them each time God’s holy name appeared in the text. I learned that as sinful men, we should not pronounce the most sacred name, written in the four Hebrew letters called the Tetragrammaton. It had to be replaced by Adonai, which means “Lord,” or by Adoshem, which means the “Lord of the Name.” Never should the holy name cross our sinful lips. I used a silver pointer to trace the words from right to left upon the scroll. My reading became confident and fluent. I stepped down to be congratulated by all. I was now a man.

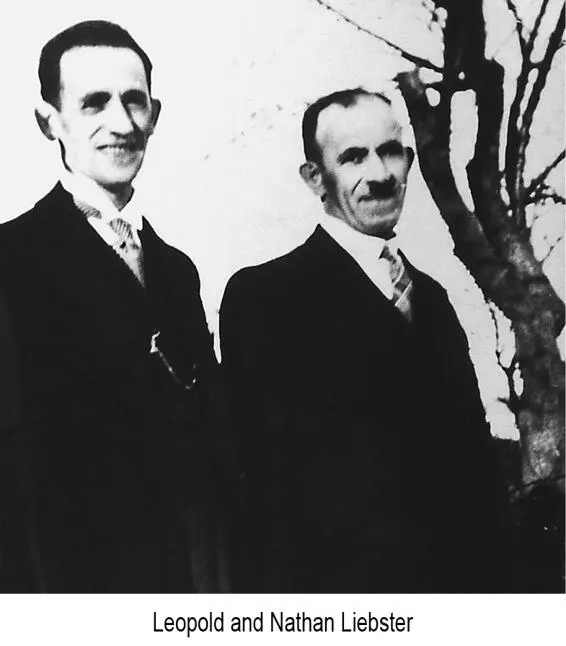

After the ceremony, the rabbi came to our home. As was traditional, we should have had a feast in honor of our special guest and to commemorate my Bar Mitzvah. Instead, the meal was very plain, and the guest list small. Father’s younger brother, Nathan Liebster, a cobbler like him, lived in Aschaffenburg. Nathan and his family were the only ones present for our celebration. Mother’s brother, Adolf Oppenheimer, couldn’t come. He lived in Heilbronn and had a hard time doing the daily chores in his men’s clothing shop. He was sickly; he just could not afford to make the trip. Father’s third brother, Leopold Liebster, a tailor who lived in faraway Stuttgart, had not been invited at all. More than distance separated my father and my uncle. Leopold had married out of our faith. His Catholic wife refused to have her children raised in the Jewish religion. Leopold did not want his children to become Catholics, so they raised the children as Protestants.

My Bar Mitzvah pleased my father, who was a devout man of prayer. My bed stood in the corner of his workshop, among piles of leather skins and shoes. From there, in the early mornings, I watched my father say his prayers. He stood at the foot of his bed, the prayer shawl upon his shoulders, the prayer book in hand, and the Tefillin (passages from the Torah written on parchment and placed in leather coverings) wrapped around his left arm and hand. Leather straps held the little Scripture case that hung on his forehead between his eyes. He chanted parts of the prayer while rocking back and forth. Each time he took the prayer shawl from his shoulder to pull it over his head, I knew that he had encountered God’s holy name. Before Dad started his day, he would daven (pray) for one hour. Even when he had to leave for the city at 4:00 a.m., he never failed to rise an hour earlier to say his prayers.

I would have loved to become a hazzan (cantor) like Grandfather. The villagers always told me that I was the exact image of Grandfather Bär Oppenheimer.

Though I looked like my grandfather, we differed in one respect. I had always been weak around blood. I remembered when I had fainted at the baby’s circumcision so many years ago. My parents may have hoped that I would follow in Grandfather Bär’s footsteps and become a shohet, but I was not suited for it. I happened to be at the kosher butcher’s one day when a cow was brought in for slaughtering. Several men surrounded the pitiable animal. They tied its legs together and flipped the animal onto its back. They held the cow’s head firmly so that it could not move. Then the shohet wielded his razor-sharp knife with a single stroke. In a split second, blood spurted from the cow’s throat. After the animal was bled, the shohet examined the contents of its stomach and looked at the liver to determine if something the cow had eaten, such as a nail, might have rendered the meat unclean. If nothing in its entrails had defiled the cow, the butchering could begin. Tradition or no tradition, the bloody sight left me feeling sick.

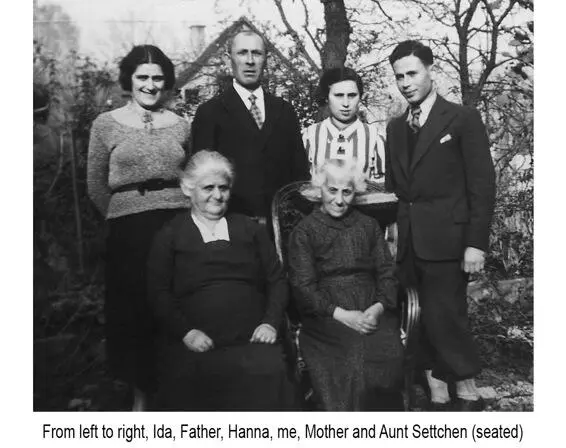

The year of my Bar Mitzvah, Hanna, my beautiful 17-year-old sister, finished her secretarial training at the paper mill. She had black velvet eyes, and wavy ebony hair, along with intelligence, determination, and good work habits. Her employer asked her to stay on at the mill, to the great relief of my parents. Our financial crisis deepened as Father’s clients took longer and longer to pay off the credit my father patiently extended. The Jewish communities knew about our dire situation. They thought of Father whenever they needed a man for the Kaddish minyan and would be very generous in covering his travel expenses. If the funeral was in a large city, Father would spend all the money he received on leather skins, much to Mother’s disappointment.

❖❖❖

When I finished school in 1929, my parents decided to accept the Oppenheimers’ offer to give me a job in their store. Since I was determined to work hard and to be self-supporting, I bade farewell to my family and to my carefree childhood days. I was a penniless, 14-year-old country boy setting off for a free education and a new opportunity in the big town of Viernheim. The Oppenheimers would give me room and board in exchange for the housework I would do for Hugo and Julius” elderly mother. I would also have to take care of my own little room in the Oppenheimers’ attic. A whole room for myself! At home I only had a bed of my own.

I didn’t realize how difficult it would be for me to trade the Lauter Valley for Viernheim. Viernheim, with its 20,000 inhabitants, was only 25 kilometers away from home. But it might as well have been on a different continent.

Viernheim was situated in a wide open land where thriving asparagus and tobacco fields sprawled under an endless sky. For centuries the fertile flood plain of the Rhine River had nourished the soil and brought prosperity to the region. Without the protection of the mountains, the land lay exposed to the four winds. I felt vulnerable in the windy flatland.

Viernheim supplied laborers for the Mercedes-Benz plant and other factories in the nearby industrial cities of Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. Thus, the population was a mix of factory workers and farmers. In the center of town were the City Hall, the Catholic church, assorted small shops, and Gebrüder Oppenheimer, with its four display windows. The well-kept homes of the rich clustered tightly around the Catholic church. A little farther away was the business school and, a few blocks behind that, the synagogue.

Our work schedule started at dawn and finished long after the store closed. Early in the morning before opening time, I had to clean the store. New merchandise had to be unpacked and the shelves stocked. Then once a week, all four shop windows had to be washed, and I had to redo the window display using no money but all my ingenuity. All day long, all week long, I climbed up and down the ladder to get items for the customers, straightened the piles of goods, waited on Julius, Hugo, and their mother, and even worked on the cars. And there was still more to do. The Oppenheimers had out-of-town customers to whom I brought samples and deliveries. My employers trusted me to drive the Citroën, even though I was only 16. Despite the extra cushion on the seat, I could hardly see over the dashboard, and to other drivers and pedestrians, it looked as if the car had no driver. I would chuckle when people panicked, thinking they were seeing a runaway car.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Crucible of Terror»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Crucible of Terror» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Crucible of Terror» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.