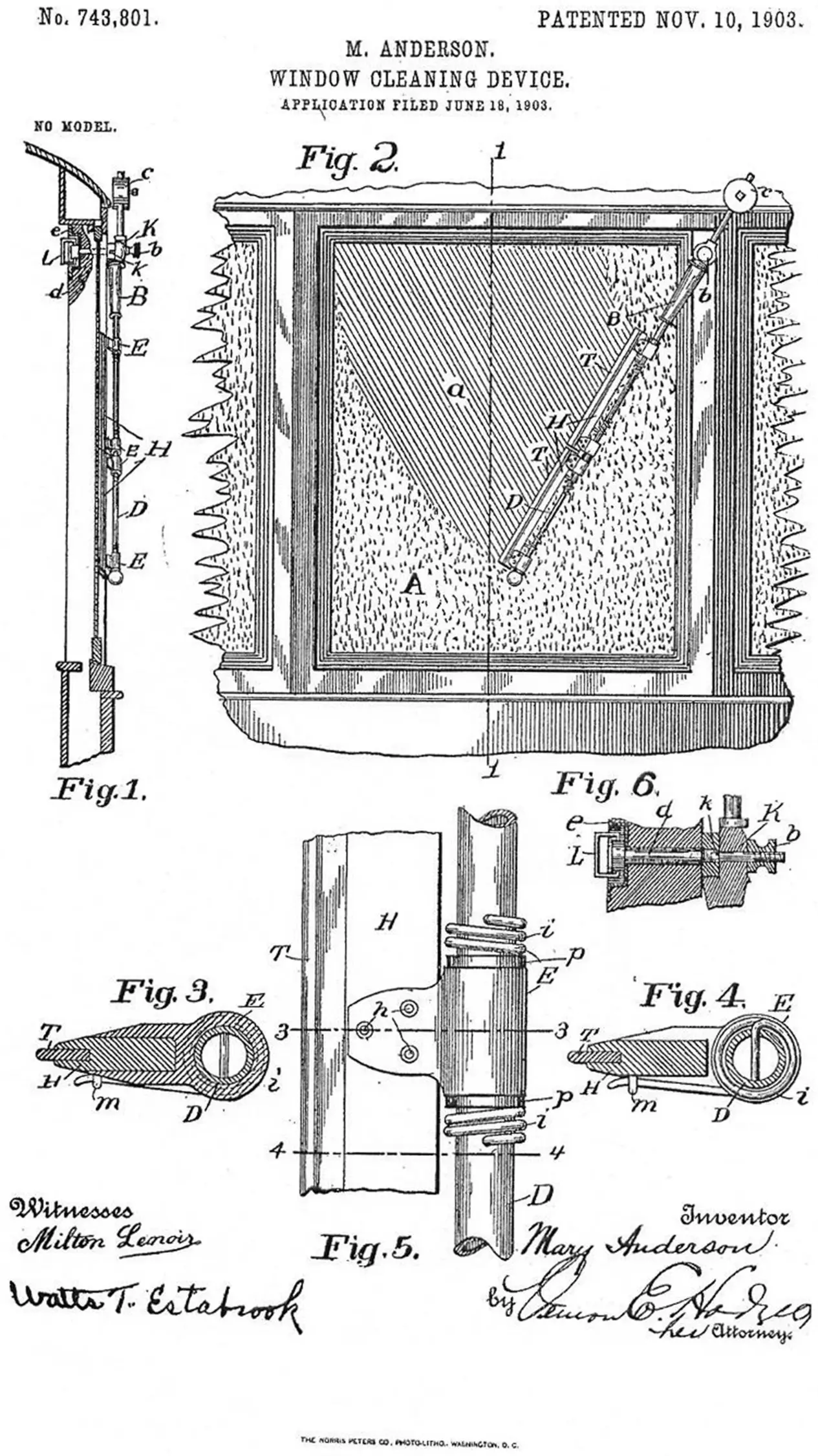

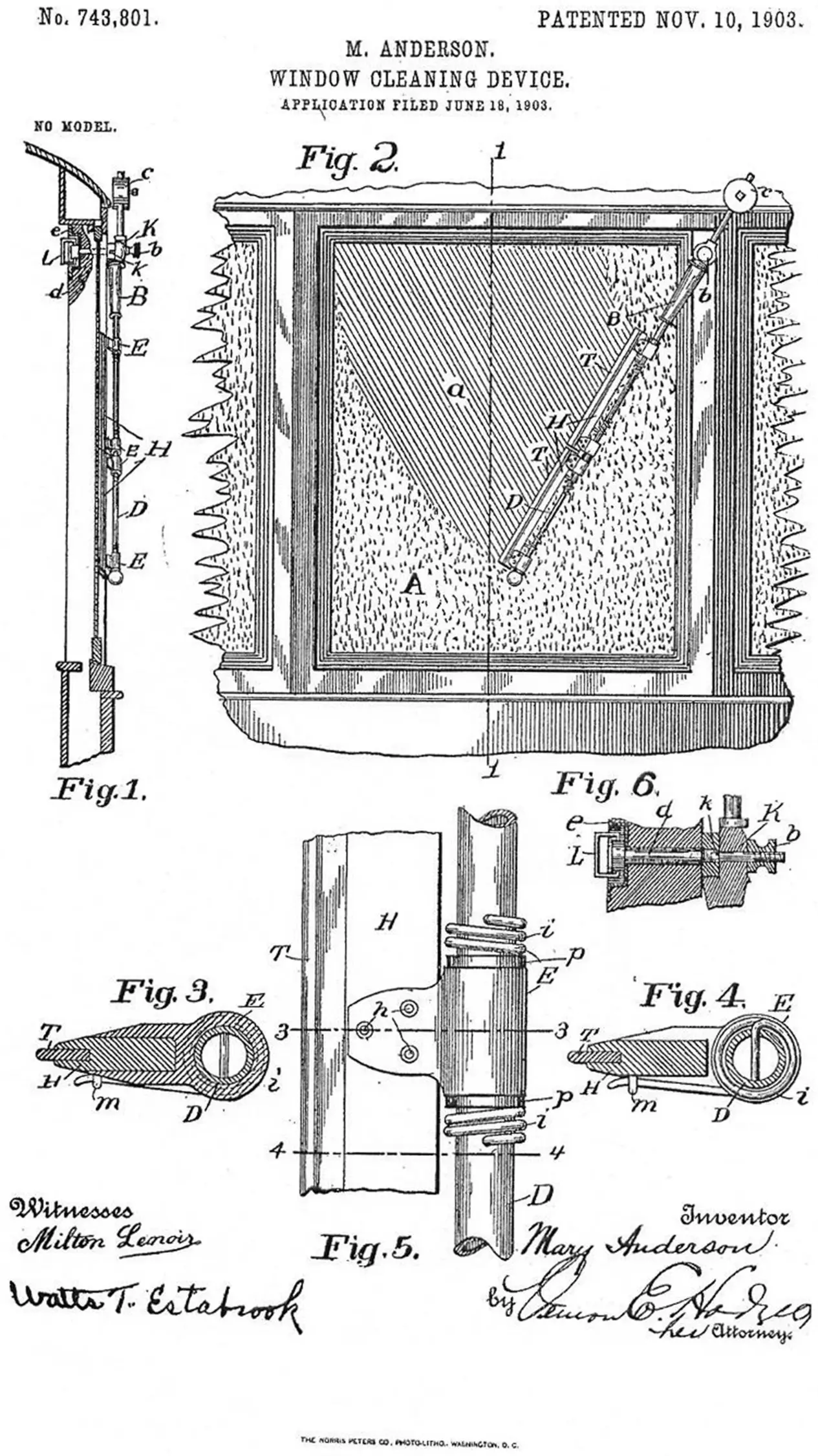

Mary Anderson began to sketch her wiper device right there on the trolley car. She then returned to Alabama, and hired a designer to sketch a manually operated device to keep a windshield clear. She then had a local company produce a working prototype, consisting of a set of wiper arms made of rubber and wood that could be controlled and operated by a lever within the trolley operator’s reach. She applied for, and in 1903 was granted, a patent for the windshield wiper, which was directed to a lever inside the vehicle, which controlled the rubber blade on the outside of the windshield. The lever was accessible to the operator, and, when the lever was pivoted, the spring‐loaded arm and the wiper blade moved reciprocally across the outside of the windshield, clearing rain, ice, sleet, mist, snow, and other unwanted materials from the windshield surface while the operator remained wholly inside the trolley. A counterweight maintained contact between the wiper blade and the windshield surface. Mary Anderson’s patented device also included a feature where the wiper assembly was removable in fair weather. Similar devices had been made earlier, but Anderson’s was the first to work effectively.

Detractors argued that her wiper would be a dangerous distraction to vehicle operators. Also, during the first decade of the twentieth century, many cars did not go fast enough to require windshields. Even though windshield wipers became standard equipment by 1916, her patent expired before she obtained any royalties for her invention.

In 1905, Anderson tried to sell the rights to her invention through a noted Canadian firm, but they rejected her, saying “We do not consider it to be of such commercial value as would warrant our undertaking its sale.” Her patent expired in 1920, just as the automobile manufacturing industry was beginning to grow. In 1922, Cadillac became the first car manufacturer to adopt Mary Anderson’s windshield wiper blade as standard equipment.

2 Brief Overview of the Law

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Throughout the rest of this text, we will be discussing how intellectual property rights are created and enforced under various statutes passed by legislative bodies, and how these rights are interpreted and enforced by the various courts of the United States and other judicial systems. Hence, before we delve into these topics, I thought it helpful if a brief overview was provided of how the systems of law emerged, and how the U.S. legal system, by way of example, is structured. This should make it easier to comprehend how the statutory laws and judge‐made laws are woven together to provide the tapestry that we know as Intellectual Property Law.

2.2 DEVELOPMENT OF THE LAW AND LEGAL PRINCIPLES

The laws of nature, or the natural laws such as the law of gravity, are universal laws, and cannot be changed by human‐made laws. Such laws would exist even if legislative acts were passed against them. A state legislature once tried to set the value of Pi as 3.000 to make calculations involving the diameter and circumference of a circle more convenient. Obviously, this did not work.

The study of law concerns human‐made laws governing relationships between people. The law refers to a set of rules and principles set up by society to restrict the conduct, and protect the rights, of its members. Each individual must control his or her behavior in such a manner that the rights of others are protected. As the urban societies of the globe grow, people interact with and depend on others to a higher degree, which requires more laws and restrictions of greater complexity to govern our behavior in a civil manner.

Laws began centuries ago as social customs and norms where it was proper for each member of the society to behave in a certain manner under particular circumstances. Tribal chiefs and, later, priests developed and enforced the laws, the latter based on laws of Divine origin.

Two codes of Divine laws are worthy of note.

The first is the Code of Hammurabi, created around 1750 BC, and it was based on the principle of an eye‐for‐an‐eye and a tooth‐for‐a‐tooth, based on one’s position in society. The early U.S. justice system was sometimes not far removed from this concept.

The Code of Hammurabi is one of several codifications of laws during ancient times. Hammurabi, the sixth Babylonian king, enacted the code, partial copies of which are engraved on a 7.5‐foot stone stele, as well as on various clay tablets discovered by modern archaeologists in 1901. The code consists of 282 laws, with variable punishments based on one’s position in society, and free man versus slave. The subjects covered in this early code include matters of contract, the terms of a transaction, the liability of a builder when a house collapses, damage to the property of another, inheritance, divorce, paternity, sexual behavior, and military service.

The preamble of the code states its purpose as:

“… to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil‐doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak; so that I should … enlighten the land, to further the well‐being of mankind.”

The code has been cast as an early fundamental law, regulating a government in the manner of an early constitution. For example, it is one of the earliest statements of the presumption of innocence, and of the rule allowing both the accused and the accuser the opportunity to present evidence on their behalves. The most repeated law from Hammurabi’s Code is the “eye‐for‐an‐eye” provision, which states as follows:

“Ex. Law No. 196. If a man destroy the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye. If one break a man’s bone, they shall break his bone. If one destroy the eye of a freeman or break the bone of a freeman, he shall pay one gold mina. If one destroy the eye of a man’s slave or break a bone of a man’s slave he shall pay one‐half his price.”

The second noteworthy set of Divine laws are the Ten Commandments, which are short and simple, and presumed to be known by every person. Knowledge of law is a presumption that has to be made. If not, anyone can plead ignorance of law and thereby avoid the operation of law. Today, most people can recall the Ten Commandments, or most of them; however, it would be impossible to know all of the laws which govern our lives today. However, there is a presumption under American law that every citizen is held to the knowledge of every law. Ignorance of the law is no defense to unlawful behavior in a nation which is governed by the rule of law.

2.4 THE FOUR TYPES OF LAW

2.4.1 Constitutional Law

Constitutional Law, or Basic Law, creates the operation of a government, defining its powers, and also establishes the limits on the government’s exercise of its powers over its people. A constitution sets forth the fundamental principles and the relationships between the state and the citizens of that state. In the United States, citizens have rights both under individual state and federal Constitutions. A purpose of the U.S. Constitution is to protect the rights of minorities against the fiats of the majority.

A statute is a law enacted by a legislative body, stating the express declarations of the will of the legislature on a given subject. A state law prohibiting gambling is an example of statutory law. Federal laws such as the Interstate Commerce Act, and municipal laws or ordinances regulating traffic, are also examples of statutes. Treaties and administrative regulations also have the same force and effect as statutes passed by the legislatures.

Читать дальше