Which protection to be used is a business decision that must be arrived at by the owner of the invention or originator of the creative work. This decision should be made with the assistance of an attorney with experience in the intellectual property law field, and after the creator or owner has a full understanding as to the best vehicle or vehicles to be used for protection.

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

Frank J. Sprague

THE ELECTRIC STREETCAR

Frank J. Sprague, born in 1857, is known as the father of electric traction vehicles. Sprague studied at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, which offered what was, at that time, probably the best training in the country for an electrical engineer. He graduated the Naval Academy in 1878 with high honors. In 1883, Edward H. Johnson, who was a business associate of Thomas Edison, persuaded Sprague to resign his naval commission to work for Thomas Edison. One of his contributions to the Menlo Park Edison laboratory in New Jersey was the introduction of mathematical methods in the work performed at the laboratory. Before he arrived, Edison’s team conducted several costly trial‐and‐error experiments. Sprague’s approach was to use mathematics to calculate the optimum parameters, thus saving much needless tinkering. Sprague also developed a mathematical determination of electrical distribution useful in planning and balancing the distribution circuits of Edison’s central electricity plants. However, in 1884, Sprague decided that his interests in the exploitation of electricity should be directed more towards power generation elsewhere, and he left Edison to found the Sprague Electric Railway and Motor Company. By 1886, Sprague’s company perfected two important inventions. The first was a constant‐speed non‐sparking motor with fixed brushes. The second was a regenerative braking system that uses the drive motor to return power to the main supply system. His motor was the first to maintain constant speed under varying load, and was ultimately endorsed by Edison as the only practical electric motor available. His regenerative braking system was important in the development of electric trains and electric elevators.

Most importantly, Sprague’s inventions included improvements to designs for electric streetcar systems that collected electricity from overhead lines. An electric street car is a vehicle that runs on track laid in the streets, operated usually in single units and most usually driven by an electric motor. A streetcar is of lighter weight as compared to conventional trains and is designed for the transportation primarily of passengers, but occasionally can be used to carry freight. Streetcars operate within, close to, or between nearby towns and/or cities on tracks running primarily on the streets.

The first mass transportation vehicle in the United States was called an “omnibus.” Pulled by horses, it had the appearance of a stagecoach. The first omnibus operated in America up and down Broadway in New York City in 1827. The first important improvement over the omnibus was the streetcar, which was also pulled by horses. However, instead of running along a regular street, streetcars rolled along special steel rails placed in the middle of the street. On January 17, 1871, a San Francisco citizen, Andrew Smith Hallidie, patented the first cable car, which used metal ropes by which cars were drawn by an endless cable running in a slot between the rails. The cables passed over a steam driven shaft in the power house. The cable systems involved laying expensive infrastructure, and were inefficient to operate because only 18% of a cable car system’s stationary engine power was applied to moving the cars, the remainder of the energy being consumed by moving the weight of the cable.

The early streetcars also sometimes used mules for motive power. Mules were thought to provide more hours per day of useful transit service than horses, and were especially popular in southern U.S. cities such as New Orleans, Louisiana, as well as in Mexico. By the mid‐1880s, there were 415 street railway companies in the United States, operating over 6,000 miles of track, and carrying 188 million passengers per year using animal‐drawn cars. In the nineteenth century, Mexico also had streetcars in around 1,000 towns, many being animal powered. Although most animal‐drawn lines were closed in the nineteenth century, a few lasted into the twentieth century and later. Toronto’s horse‐drawn streetcar operations, for example, ended in 1891. In New York City, the regular horse‐powered service lasted until 1917, and in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, until 1923. The last regular mule‐drawn cars in the United States operated in Sulphur Rock, Arkansas, until 1926.

The obvious advantages of a system that eliminated animal drive power included doing away with the need to feed the animals, and, more importantly, cleaning up their waste after they ate. In Chicago, for example, there were an estimated 6,600 horses owned by the street railways in the 1880s, dumping a considerable amount of manure and urine on the streets. Further, many horses were killed in the Chicago Fire of 1871, and then an influenza‐like equine epizootic decimated the surviving horses the following year. In 1867, some street railway systems tried to replace horses with small steam locomotives, but the public objected to the smoke, noise and sparks that they generated.

Some early streetcars also depended on power supplied by storage batteries; however, these proved to be very expensive and inefficient. Invention of the dynamo or generator led to the application of electric power by means of overhead electrified wires, and to streetcar lines which subsequently proliferated in the United States, Europe, and the rest of the world. Prior to Sprague, there had been early experimental electric railways. Most of these were erected as electrical exhibitions at fairs and expositions as tourist attractions, and were usually dismantled after the exhibitions closed.

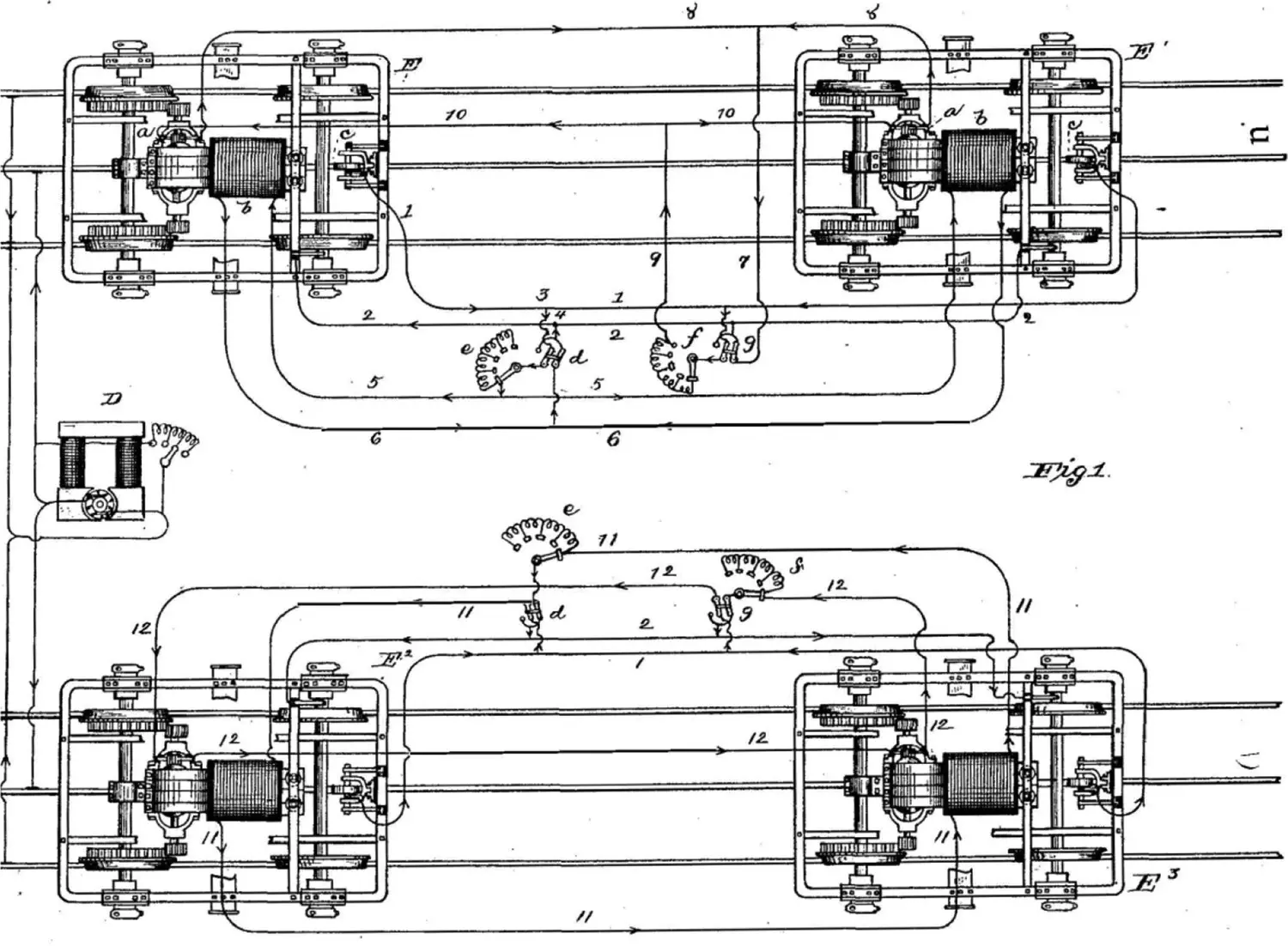

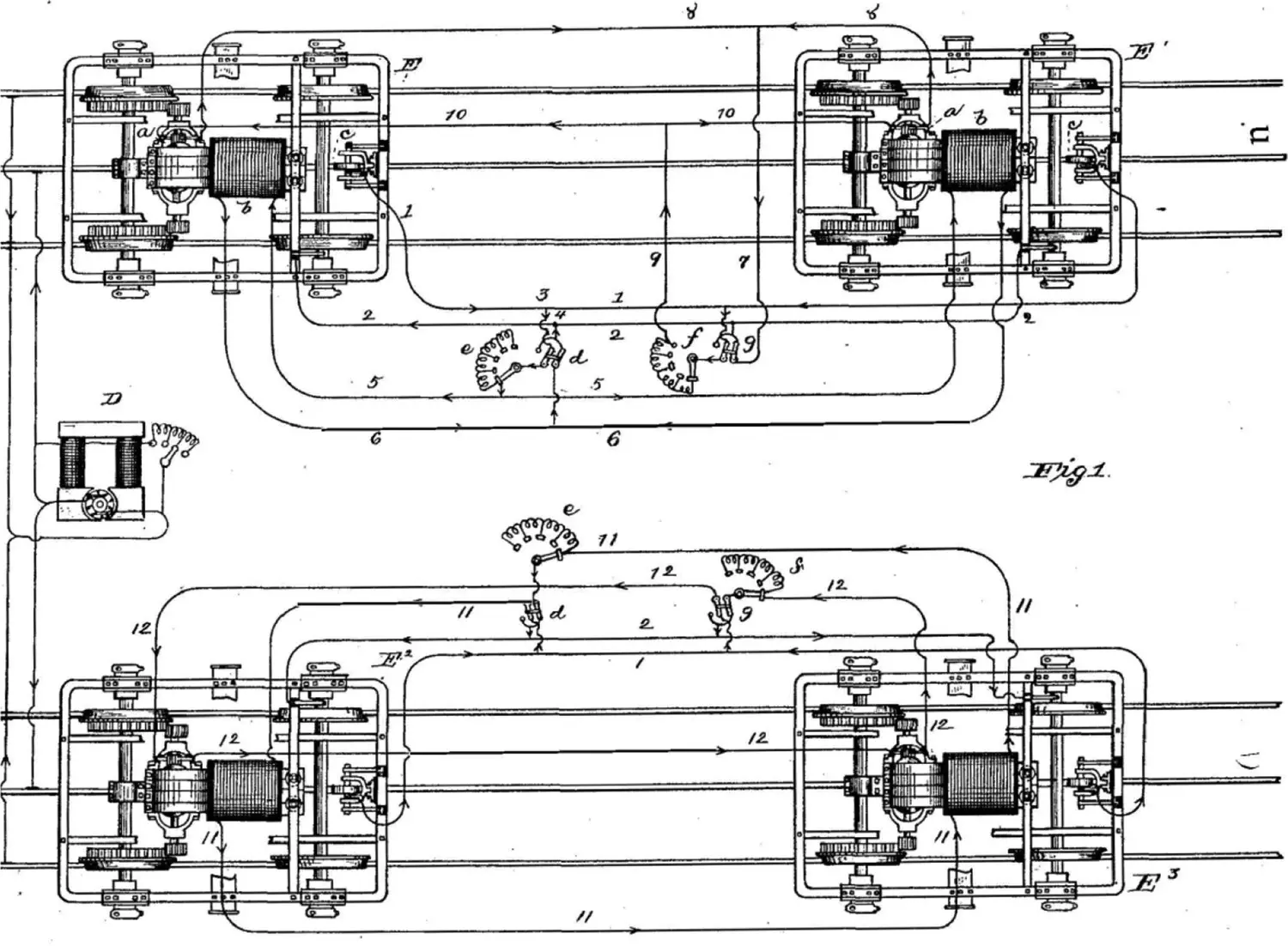

In 1888, Sprague developed streetcars that collected DC electricity from overhead wires, using a spring‐loaded trolley pole that had been invented in 1880. The trolley pole comprised a bent piece called a “bow,” or a collapsible and adjustable frame called a “pantograph,” which was used in foreign countries as compared to the single‐trolley pole in the United States. The ground return was through the iron street rails. Sprague’s trolley pole traveled along the wire above the streetcar. The Sprague system motors were mounted beneath the cars, and centered on the axles, with both motors operated by a single control switch inside the car. Variable speed of the motors was obtained by varying the resistance of the field winding of the motors traversed by the current. Power was supplied through the overhead wire and the trolley pole. Many of these features were also used on subsequent light railways. General Electric and Westinghouse adopted many streetcar features on their railroad equipment.

After testing his trolley system in 1887 and 1888, Sprague installed the first electric street railway system in Richmond, Virginia. This was the first large‐scale and successful use of electricity to operate an entire system of city streetcars. Overhead wires were installed over the Richmond city streets, and a spring‐loaded streetcar pole would contact the electric wire. Back at the power house, steam engines turned huge generators to produce the electricity required to operate the streetcars. The name “trolley cars” was soon developed for the streetcars powered by electricity. The Richmond electric streetcar system, 12 miles long and with 40 cars, was in operation by February 2, 1888, and had a significant impact upon the burgeoning electric trolley industry in the United States. Sprague’s use of a trolley pole for DC current pick‐up from a single line, with ground return via the street rails, was the pattern that was eventually adopted in many other cities. The hills of Richmond, Virginia, which included grades of over 10%, provided an excellent proving ground for acceptance of Sprague’s new technology. The Richmond electric streetcar system remained in service until November 25, 1949.

Читать дальше