National and Pacific City Lines and their suppliers entered into various oral and written agreements where the operating companies for the transit systems, National and Pacific, purchased preferred stock from the supplier defendants at prices in excess of the prevailing market prices, amounting to over US$9 million. The money received from the sale by National and Pacific of such stock was used to acquire control of, or a substantial financial interest in, various local transportation companies throughout the entire United States. The respective supplier defendants then entered into separate 10‐year contracts with National and Pacific, under which all of the buses, tires, tubes, and petroleum product requirements of the National and Pacific operating companies were purchased from the supplier defendants, with an agreement not to buy any of these products from any party competing with the supplier defendants. Existing purchase contracts of all the operating companies with competitive suppliers were terminated at their earliest possible time, and the operating companies began equipping all their units with defendant supplier products, including buses, to the exclusion of any products competitive with them. National and Pacific also agreed that they would not renew or enter into any new contracts with other competitors of such products, or change any then existing equipment or purchase any new equipment using any fuel or means of propulsion other than gasoline.

National City Lines had been organized in 1936 as a holding company to acquire and operate local transit companies. Pacific City Lines was organized to acquire local transit companies on the Pacific coast, and began business in January 1938. There was another company, American City Lines, that was organized to acquire local transportation systems in the larger metropolitan areas in various parts of the United States in 1943, and American merged with National in 1946.

In a decision rendered by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals on January 31, 1951, upholding the previous District Court’s and jury’s conviction of the defendants on charges of monopolization, the Appellate Court found that, in 1938, National City Lines conceived the idea of purchasing transportation systems in cities where streetcars were deemed to be no longer practical, possibly due to the Depression and a trend at supplanting streetcar systems with passenger buses. National City Lines’ capital was limited, and its earlier experience in public financing showed that it could not successfully finance the purchase of an increasing number of operating companies in various parts of the United States by normal financing means. As a result, National City Lines devised the plan of procuring funds from manufacturing companies whose products National City’s operating companies were using constantly in their bus operating business.

National approached General Motors, which manufactured and delivered buses to the various sections of the United States. National also approached Firestone, whose business of manufacturing and supplying tires also extended throughout the United States. In the Midwest, where a large part of its operating subsidiaries were to be located, National City Lines solicited investment of funds from Phillips Petroleum, which operates throughout the Midwest but not on the east or west coast. Pacific City Lines undertook the procurement of funds from General Motors and Firestone, as well as from Standard Oil of California. Mack Truck Company was also solicited for funds. The Court of Appeals held that evidence was clear that, when any one of these manufacturing suppliers was approached, they appeared interested in helping finance National and Pacific under the condition that it should receive a contract for the exclusive use of its products in all of the operating companies of National and Pacific, so far as buses and tires were concerned, and, as to the oil companies, in the territory served by the respective petroleum companies.

It appears from the Appellate Court opinion that the District Court jury was justified in inferring that the proposal for financing came from National City Lines, but that the proposal of exclusive contracting was created by the suppling companies. Eventually, each supplier entered into a written contract of long duration, whereby National and Pacific City Lines, in consideration of the supplier’s help in providing financing, agreed that all of National’s and Pacific’s operating subsidiaries should use only the supplier’s products.

Based on these facts, the Court of Appeals of the Seventh Circuit upheld the conviction of the defendants on charges of monopolization. Another factor in the case was that, after National City Lines and Pacific City Lines purchased the various streetcar operating companies, they ripped up the rails in the different cities, tore down the electric lines, and dismantled and even sometimes burned the streetcars. Usually, the systems would be converted to buses within 90 days of National or Pacific’s financial involvement. The first electrified surface transportation system that was demolished and replaced by buses was in New York City.

Strangely enough, however, even though the federal government won the lawsuit against these defendants, no meaningful penalty was imposed on anyone other than small symbolic fines, such as a US$5,000 fine levied on the companies, and a US$1 fine on the individuals. Commentators have noted that it is possible that, at this time, the Truman administration decided it required the undivided assistance of General Motors in fighting the ongoing Korean War and also in pursuing the Cold War against the former Soviet Union. Maybe the government at that time, decided that the support of large corporations was a higher priority than having electric mass transit systems operating in major population areas. Thus, it appears that there may have been economic reasons for the demise of electric streetcar systems; however, in the opinion of this writer, this natural progression was greatly assisted by the “conspiracy” discussed earlier.

In the 1920s, many American cities and towns were connected by a network of electric railroads and interurban electrified trolley cars. Within the cities, electric street railways, trolleys, and elevated trains moved large numbers of people easily and inexpensively. Between 1920 and 1955, General Motors, through National City Lines and Pacific City Lines, bought up more than 100 electric mass transit systems in 45 cities, allowing them to deteriorate and then replace them with rubber‐tired, diesel‐powered buses, which some writers say are more expensive, less efficient, and much filthier than electric rail systems.

Cities where electric rail systems were eliminated and replaced through this conspiracy to monopolize included New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, St. Louis, Oakland, Salt Lake City, and Los Angeles. The only large city in California where National or Pacific did not take over the transit company was San Francisco, whose transit system was owned by the city.

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

Mary Anderson

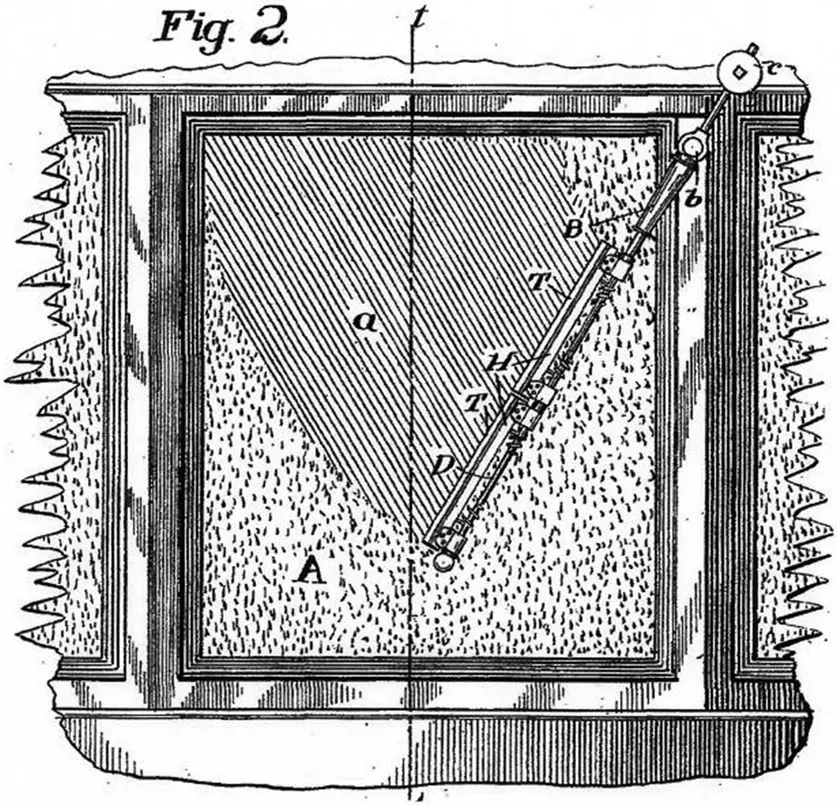

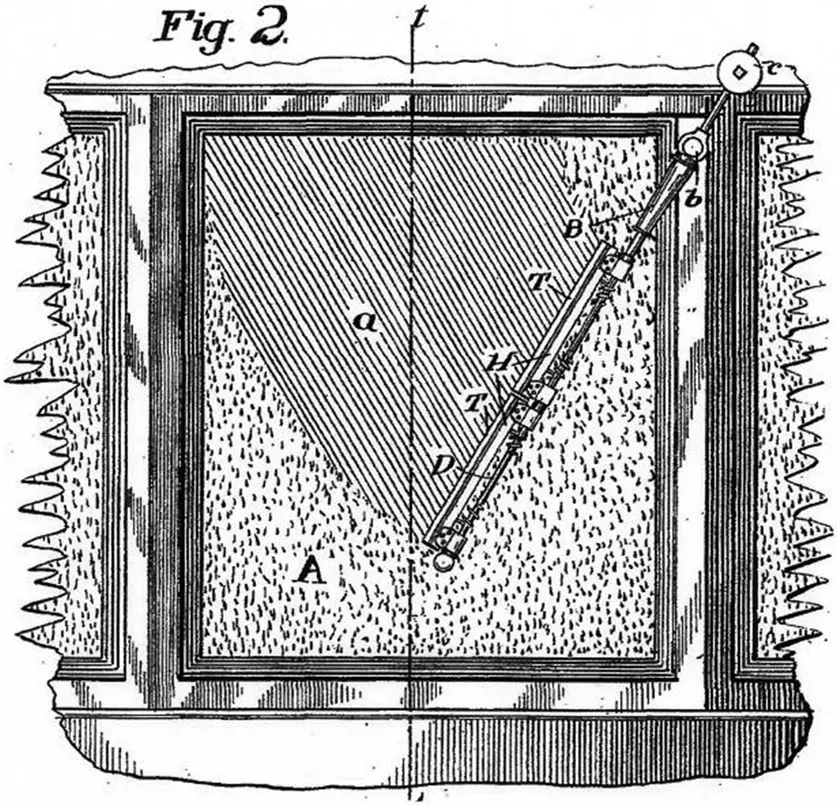

WINDSHIELD WIPER BLADE

Mary Anderson was a real estate developer, rancher, and inventor of the windshield wiper blade. She received her first patent, No. 743,801, in November 1903 for an automatic car window cleaning device that was controlled from inside the vehicle.

Mary was visiting New York City in the winter of 1902, and, while riding in a trolley car on a particularly icy day, she noticed that the motorman drove with both panes of the double‐front window open because of the difficulty in keeping the windshield clear of falling sleet. She also observed that the trolley driver often had to stop the trolley, and go outside to clear the window. The trolley’s front‐split, two‐panel window was designed for bad‐weather visibility, allowing the driver to move the panel comprising the snow or rain‐covered section out of his line of vision. However, the multi‐pane windshield system worked very poorly by exposing the driver’s uncovered face (not to mention all the passengers sitting in the front of the trolley) to the falling precipitation. Notably, the multi‐pane construction did not improve the operator’s ability to see where he or she was going.

Читать дальше