Other types of animals in these studies, including guinea pigs, were not found to be susceptible. The investigators credited the director of the Commission, Henry Beeuwkes, with obtaining animals for experimentation from areas of the world away from West Africa. A tragic note was found at the head of the report that the lead author, Adrian Stokes, “fell victim to yellow fever.” It was suspected that the infection was acquired in the laboratory. Yellow fever surely took its revenge on those seeking to unlock its secrets, including Jesse W. Lazear, of the Commission led by Walter Reed, and Hideyo Noguchi.

While the report by Stokes et al. on the susceptibility of rhesus monkeys to yellow fever ushered in a laboratory model for study, monkeys were expensive and complex to manage. In 1930, Max Theiler, the investigator who was later to receive the Nobel Prize for developing the yellow fever vaccine, 17D, demonstrated the susceptibility of white mice after intracerebral inoculation ( 60, 61, 62). This model allowed the development of the mouse protection assay, which, in turn, facilitated large-scale epidemiological studies of viral prevalence ( 53).

Isolation in monkeys, and particularly in mice, was exceptionally productive in the 1930s for filterable viruses that caused epidemics of encephalitis. These viruses were transmitted by mosquitoes and came to be called “arthropod-borne” ( 25), later shortened to “arbovirus.” The first of these agents was St. Louis encephalitis virus, named after the city in which an epidemic occurred in 1933. Virus was isolated in monkeys by R. S. Muckenfuss et al. ( 43) and in mice by L. T. Webster and G. L. Fite ( 66). Another epidemic encephalitis, which had blanketed a large portion of the globe and put millions of people at risk, was noted in Japan as early as the 1870s. It was originally called Japanese B encephalitis to distinguish it from encephalitis lethargica, the first recognized epidemic encephalitis. A number of laboratories reported isolation of Japanese B virus in the 1930s, including that of R. Kawamura, which isolated the virus in monkeys and mice ( 29). Subsequently, several other epidemic arboviral encephalitides were recognized in the 1930s, and their etiological filterable viruses were also isolated in the same hosts ( 3a).

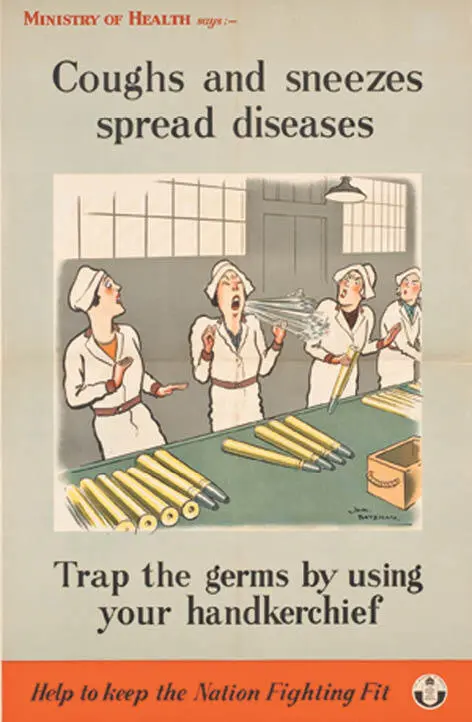

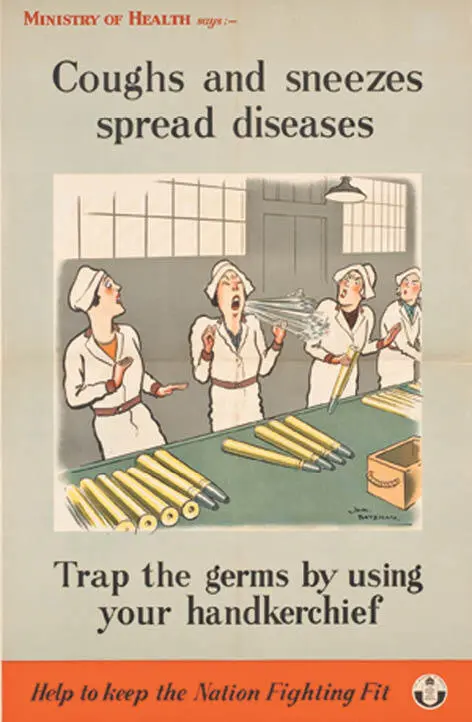

The influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 is one of the greatest natural disasters of recorded history. First recorded at an Army Camp in Kansas in 1918 toward the conclusion of World War I, influenza killed more people worldwide than did that conflict. The exact number will never be known because of incomplete global health records, inaccurate records of death, and censorship associated with the war. One analysis estimated that between 24.7 and 39.3 million lives were lost to the pandemic worldwide ( 46). The war facilitated the pandemic in concentrating and moving troops and disrupting the civilian populations. Reciprocally, conduct of the conflict was hampered on both sides by disabled troops ( Fig. 5). Rail travel and transoceanic steamships took the pandemic to all but a few remote locations. In other influenza epidemics, it has been the very young and the elderly who have suffered the brunt of the mortality. However, the unique feature of the 1918–1919 pandemic of influenza was the predilection for killing previously healthy young adults. It now seems likely that such mortality resulted from an overexuberant host response, with the body’s own defenses turning against the body in an attempt to ward off infection.

Figure 5“Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases,” a slogan and poster campaign that was designed to cut down on the spread of respiratory diseases in the United Kingdom in World War II. Disease was portrayed as hampering the war effort at home. No doubt lurking in the minds of the Ministry of Health officials were the devastating effects of the 1919 influenza pandemic. (Courtesy of Yale University, Harvey Cushing/John Whitney Medical Library.)

doi:10.1128/9781555818586.ch2.f5

The effects on society and on individuals are poignantly described in Katherine Anne Porter’s story Pale Horse, Pale Rider ( 49). The medical historian Alfred W. Crosby said of Porter’s story, “It is the most accurate depiction of American society in the fall of 1918 in literature” ( 10). Porter was herself desperately ill and lost her lover, an Army lieutenant, to influenza. In the fictionalized account in Pale Horse, Pale Rider , the lover of the protagonist, Miranda, describes the effects of the disease on the city: “‘It’s as bad as anything can be,’ said Adam, ‘all the theaters and nearly all the shops and restaurants are closed, and the streets have been full of funerals all day and ambulances all night. . . .’” Miranda is taken to the hospital while Adam is out getting them ice cream and hot coffee. She never sees him again, for he was not allowed to visit her. Tragically, she learned of Adam’s death in an army camp hospital upon her recovery. Crosby reports that Porter said of the effect of the pandemic on her life, “It just simply divided my life, cut across it like that.” ( 10). It was true, commented Crosby, for many of her generation. He dedicated his account of the pandemic, America’s Forgotten Pandemic , “To Katherine Anne Porter, who survived” ( 10).

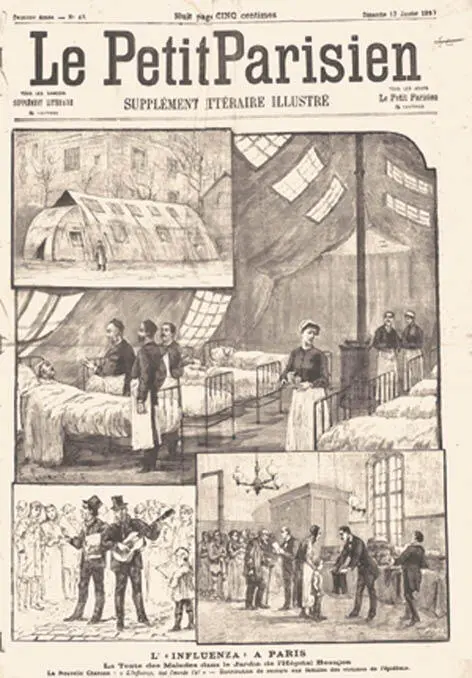

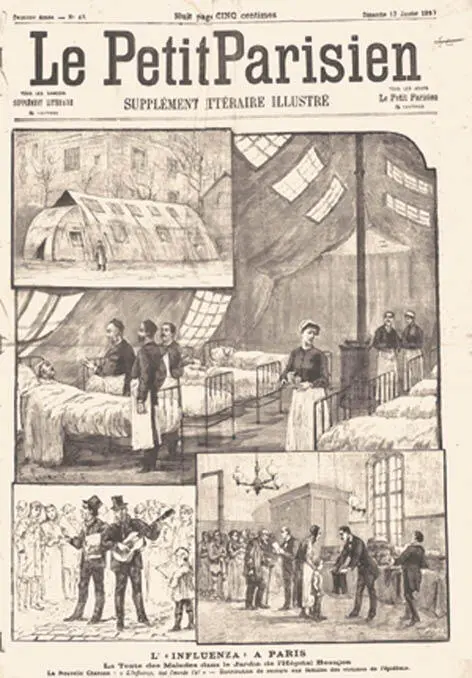

Although the pandemic of 1918–1919 was shattering on a global scale, “The first pandemic of influenza in the bacteriological era,” according to Richard Shope, “was that of 1889–1890” ( 56) ( Fig. 6). During that epidemic, R. Pfeiffer isolated the bacillus Haemophilus influenzae ( 48). Pfeiffer held that the bacillus was present in cases associated with influenza but not in other individuals. John R. Mote reviewed the literature disputing this view but nonetheless assented that “. . . Pfeiffer’s bacillus was for years considered by many workers to be the cause of epidemic influenza” ( 42). As Patrick Playfair Laidlaw described in his Linacre lecture, H. influenzae “. . . had held an almost undisputed position since the end of the pandemic 1899–1890” ( 31).

Figure 6L’influenza à Paris. This cover is from a Parisian weekly in 1890 during the influenza pandemic of 1889–1890. Originating in Russia and spreading westward, influenza became known as “Russian flu.” The cover depicts four scenes relating to the epidemic in Paris (clockwise from top left): a tent set up in a hospital courtyard, the interior of tent ward for the sick, the distribution of clothes to families of victims, and two men singing a new song, “ L’influenza, tout l’monde l’a! ” (“Influenza, Everyone Has It!”). (Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.)

doi:10.1128/9781555818586.ch2.f6

The accepted ethical norms of disease investigation in humans seemed to be suspended when the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 came toward the end of World War I. Historically, wartime overthrew many usual constraints on the study of illness. As the science writer Gina Kolata put it, “But in 1918, such ethical arguments were rarely considered. Instead, the justification for a risky study with human beings was that it was better to subject a few to a great danger in order to save the many” ( 30). Negative studies with sailors in Boston, MA, and San Francisco, CA, were recounted by Kolata: intense exposure of presumed susceptible subjects to infected persons and their mucus, blood, exhalations, and coughs failed to induce the disease. While other groups of investigators appeared to have some success, the results were not consistent enough to reach a conclusion. As expressed by Laidlaw, one of the investigators who successfully transmitted influenza to ferrets, “One can never be sure that the experimental subject is susceptible and therefore negative results can be discounted; while positive results, though perhaps more significant, are always open to the suspicion that infection was picked up in some accidental manner” ( 31).

Читать дальше