The sympathy Tejanos displayed for the limited independence movement brought destruction to the province, for civil war did not end following the defeat of Las Casas. One Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, from Nuevo Santander, assumed Hidalgo’s revolutionary mantle. Apparently encouraged by US officials wanting to develop an appropriate foreign policy toward New Spain once that country had achieved its independence, Gutiérrez de Lara worked to wrest Texas from royalist control, rejecting like other liberals in New Spain, the Bourbon belief in the divine right of kings. He encouraged Tejanos, in documents he and his supporters introduced into Texas in early summer 1812, to discard the royal authority under which they had long lived and through revolution, create a political world granting sovereignty to the mass of people (or in the Spanish tradition, to the ayuntamiento). Accompanied by Augustus W. Magee, a former US Army officer at Natchitoches, Louisiana, whose design and those of 130 volunteers was on Texas land, Gutiérrez forded the Sabine River in August 1812 at the head of the Republican Army of the North and captured Nacogdoches. Soon, the expedition exceeded 700 in number, attracting recruits from among Anglo volunteers in Louisiana and members of the local militia. From East Texas, the expedition marched toward Central Texas, captured La Bahía and San Antonio, and proclaimed Texas as an independent state in the spring of 1813. But in August, a royalist force led by José Joaquín Arredondo crushed the rebels (sans Gutiérrez de Lara, who by then had lost favor among the republicans and had been replaced as commander) south of San Antonio at the Battle of the Medina River. It was the bloodiest battle ever fought on Texas soil, with some 1300 rebel soldiers killed. Soon thereafter, the royalists shot 327 suspected rebel sympathizers in San Antonio, and Nacogdoches became the scene of another bloody purge committed by one of Arredondo’s lieutenants. The royalists now ravaged the ranchos, compelling many Tejanos to flee across the Sabine River into Louisiana. For the next several years, these agents of peninsular and criollo power dominated the region, living off the land and harassing the frontier people, most of whom sympathized with the insurgents. By 1821, Spanish rule ended when New Spain achieved its independence. Nacogdoches, with much of its populace having fled, faced extinction as a community.

Throughout the colonial era, the number of people who lived in Texas fluctuated, reaching the aforementioned figure of about 4000 early in the nineteenth century, then dwindling to 2240 (excluding soldiers) by 1821. Remarkably, these few thousand pobladores succeeded in transporting traits of their heritage into the next era. Numbers by themselves, therefore, are deceptive: they do not testify to enduring aspects of the Tejanos, among them a unique character as a people of the frontier. As already indicated, the central government of Spain did not strictly dictate life in the Far North. Relative isolation had always guaranteed a modicum of independence and honed the development of attitudes and skills necessary for survival in an unforgiving environment. Even the governor and other royal officials pursued a compromise with viceregal rule, adhering to the old dictum of obedezco pero no cumplo (I obey but do not comply). Military officials behaved no differently. And the Church, burdened as it was with debt and commitments to missionary work, could hardly have acted as an arm of the state.

The atmosphere in colonial Texas, therefore, encouraged informal community building. Tejanos sought their own economic ends by selecting the most convenient and profitable markets for their livestock; this meant turning to Louisiana and even to the United States to engage in contraband trade. The ayuntamiento at times acted as a legitimizing agent when local necessities clashed with imperial dictates. Such adjustments to circumstances at hand permitted Tejanos to survive quite well as a community after the end of Spain’s presence in their land.

The Far North also produced traits of ruggedness that traversed cultures and nationhoods. Spaniards in the hinterlands carried the task of establishing roots and the responsibility of perpetuating their civilization hundreds of miles from previous settlements. On the range, settlers had to perfect their skills in handling horses to exact a livelihood from a predominantly ranching culture. The “Norteño” variety of Mexican culture, some historians hypothesize, resulted from these experiences. The north fostered egalitarianism, the will to work, an implied strength and prowess, as well as determination and courage in the face of danger.

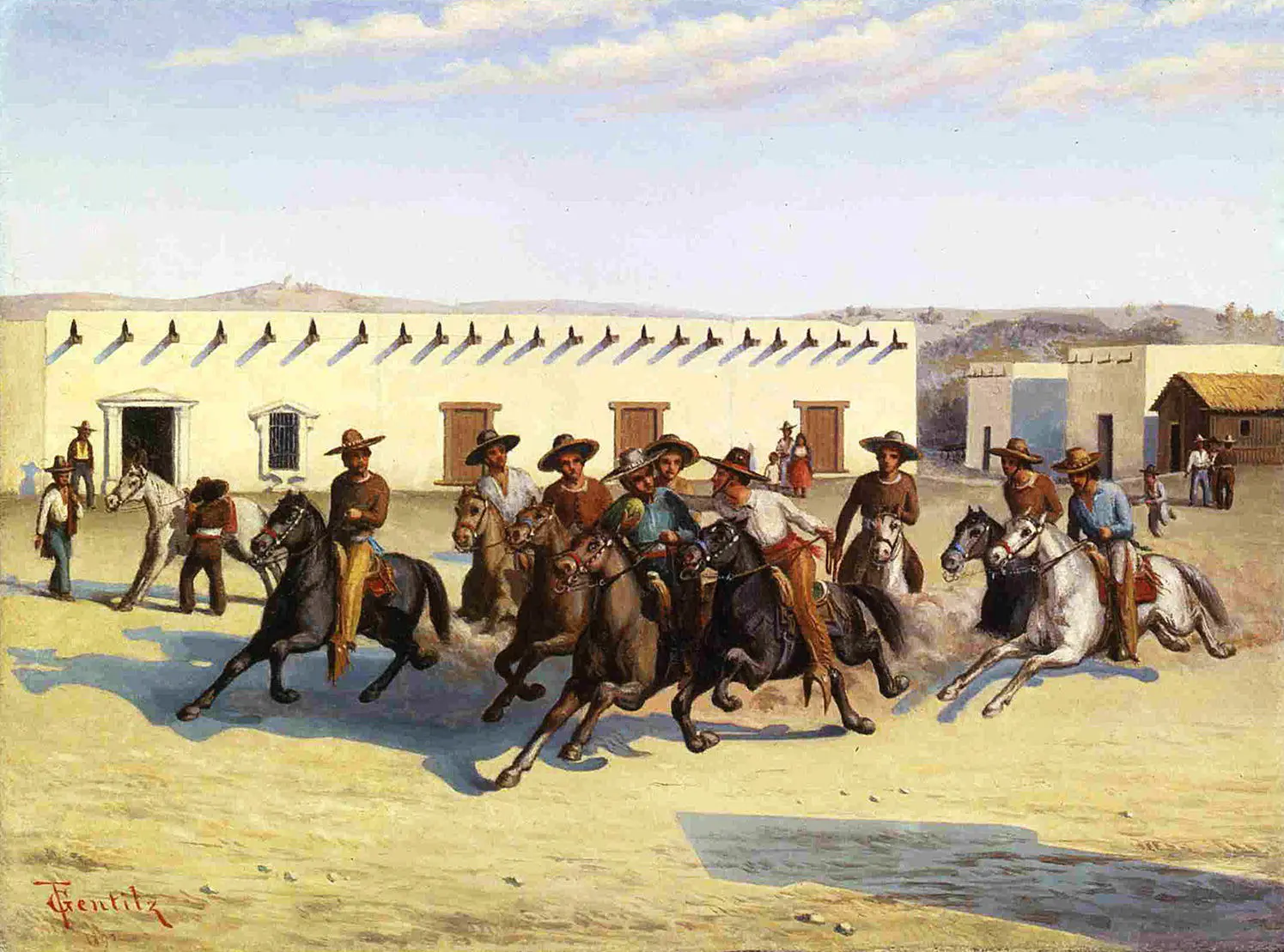

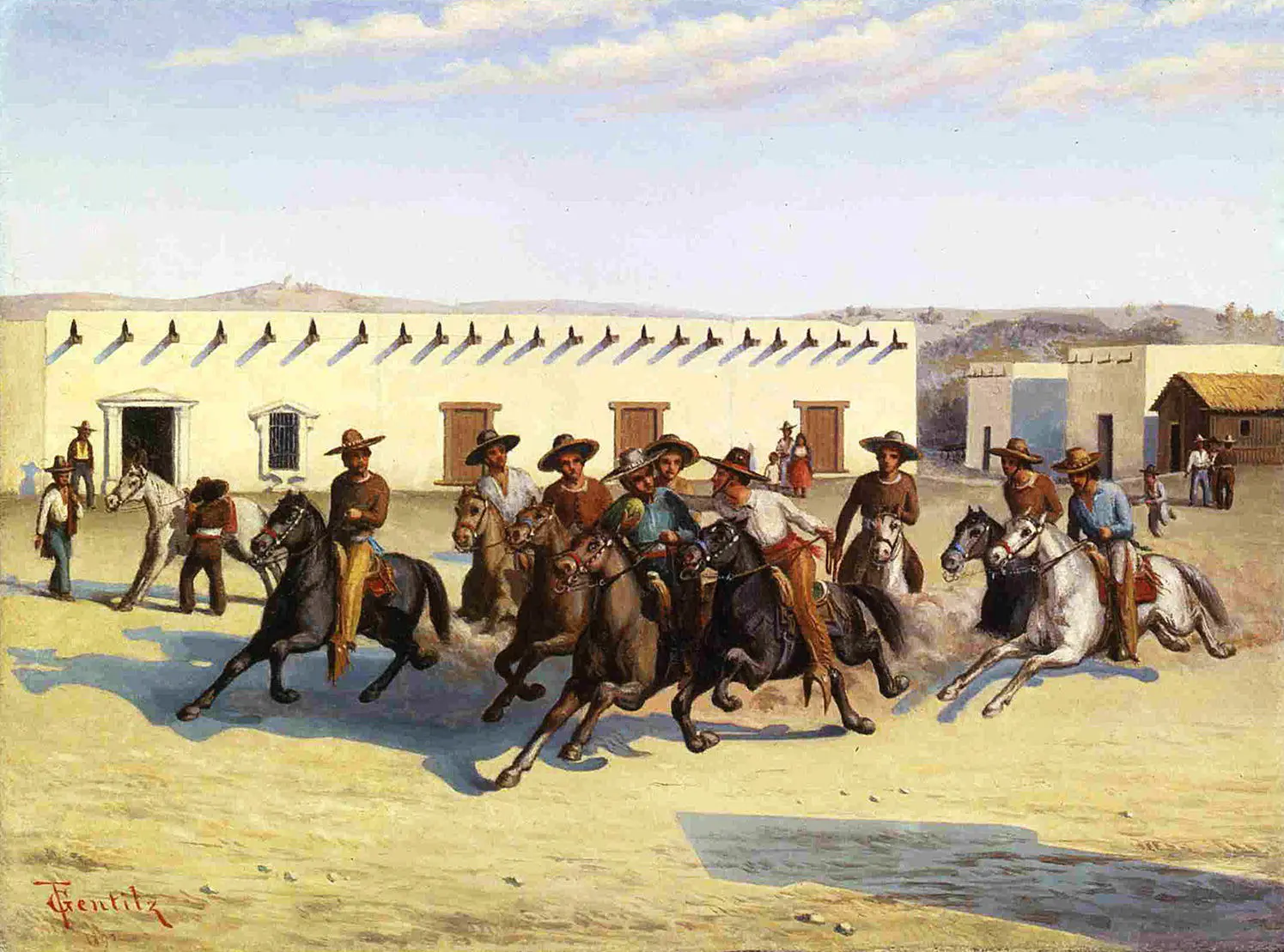

At the end of its war for independence, which ended in 1821, New Spain effectively preserved traditions with origins in the Iberian Peninsula, which Tejanos transmitted past 1821. Some customs applied to the ranching economic order. Spanish‐Mexican terminology, riding gear, and methods of working the range became etched into Anglo American culture. Among familiar ranch terms are “buckaroo” from vaquero , “cinch” from cincha , “chaps” from chaparejos , “hoosegow” from juzgado , and “lasso” from lazo . The rodeo, a semiannual roundup of livestock to determine the ownership of free‐ranging animals, evolved into a highly competitive sport in the Anglo period ( Figure 2.7).

Also perpetuated were legal practices that had derived from Spanish precedent. Iberian laws, revised for application to frontier situations, allowed outsiders to become part of a family unit. Long‐standing rules applicable to community property also lingered: couples shared jointly any assets they had accumulated while married; a woman could keep half of all financial gains the couple earned; and a husband could not dispose of the family’s holdings without his wife’s consent. Women also retained the right to negotiate contracts and manage their own financial affairs.

Furthermore, the Spanish tradition protecting debtors prevailed. Over the centuries, neither field animals nor agricultural implements could be confiscated by creditors, and in the subsequent era, this safeguard applied to a debtor’s home, work equipment, and animals, and even his or her land.

The legacy of Spain to the Texas experience thus makes for an extensive list that runs the gamut from the esoteric, such as legal influences concerning water laws, to the prosaic. Among the latter are contributions to a bilingual society in various sections of the modern State of Texas, Spanish loan words (for example, mesquite and arroyo ), delectable Spanish‐Mexican foods, styles of dress, geographical nomenclature (every major river in Texas bears a Spanish name, for example), and architecture. Empires might wane, but their cultures endure.

Figure 2.7 Corrida de la Sandía (Watermelon Race) by Theodore Gentilz. Part of the Celebration of the Día de San Juan.

Source: Yanaguana Society Collection, Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library.

Although Spain’s rule over Texas left a lasting imprint on the outpost, few Tejanos mourned its replacement in 1821 by an independent Mexico. Communities had valued their relative autonomy on the hinterland, but they had wanted better administration and military protection. Simultaneously, Tejanos resented the bureaucratic restrictions they believed discouraged profit making in ranching, farming, and other forms of commerce. Spain had not convinced many people to relocate into the wilderness region; a hard enough task given the fact that frontiers hold out few migrational pull factors, nor did sufficient population pressures exist in the interior to push Mexicans northward. Yet some Tejanos saw the solution to their myriad problems–among them Indian depredations and economic underdevelopment–in the arrival of new settlers, in the spread of urban settlements, and in the growth of the pastoral industries. Thus, although Spain retained sovereignty over Texas for 300 years and Hispanic culture endured there well past 1821, Spain had left a community of people still groping to devise their own survival strategies, political and otherwise. Therefore, in the era of Mexican rule in Texas, 1821–36, the pobladores would continue to pursue political solutions more appropriate to their local conditions and less relevant to the political aims of their national government.

Читать дальше