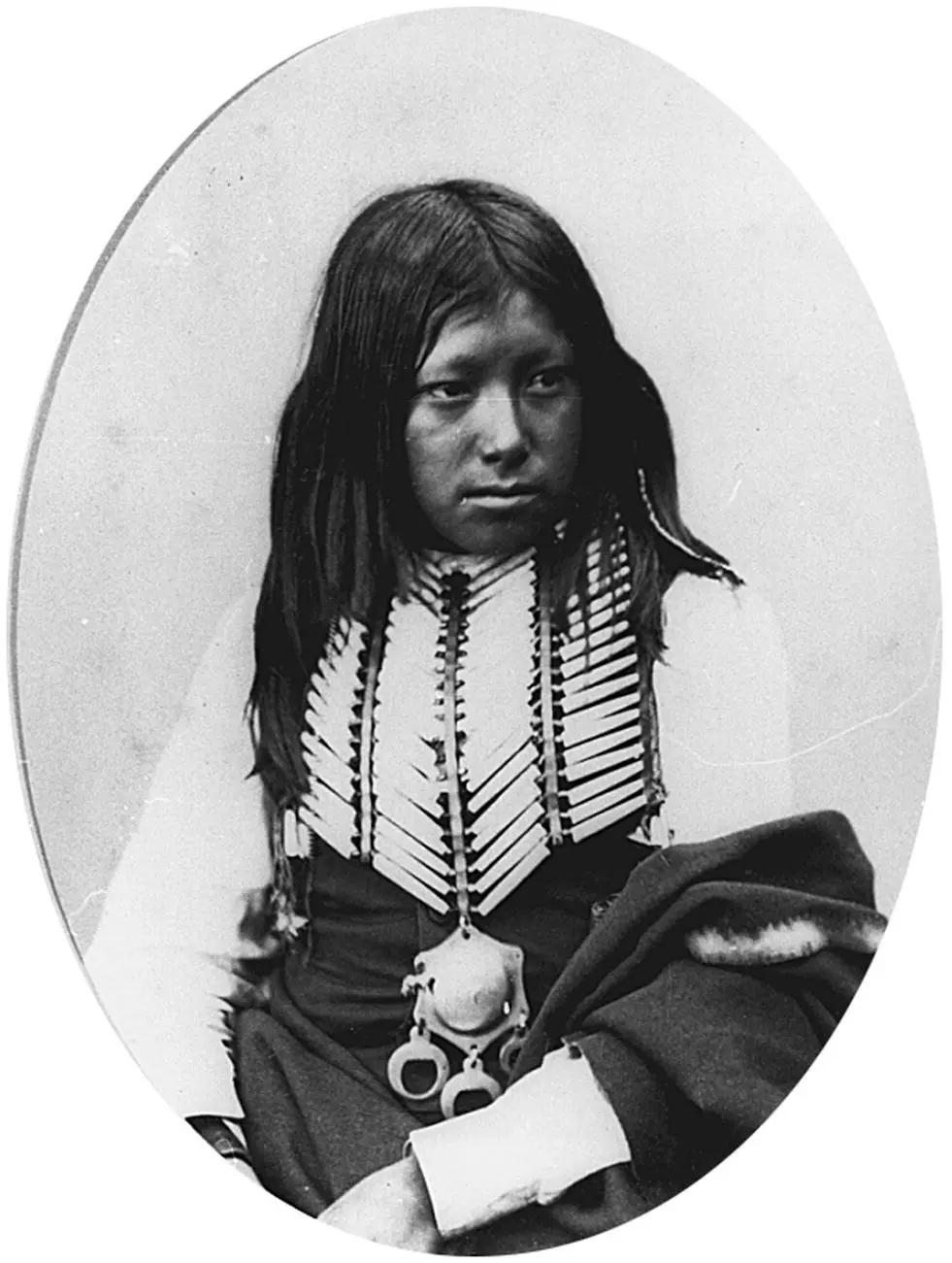

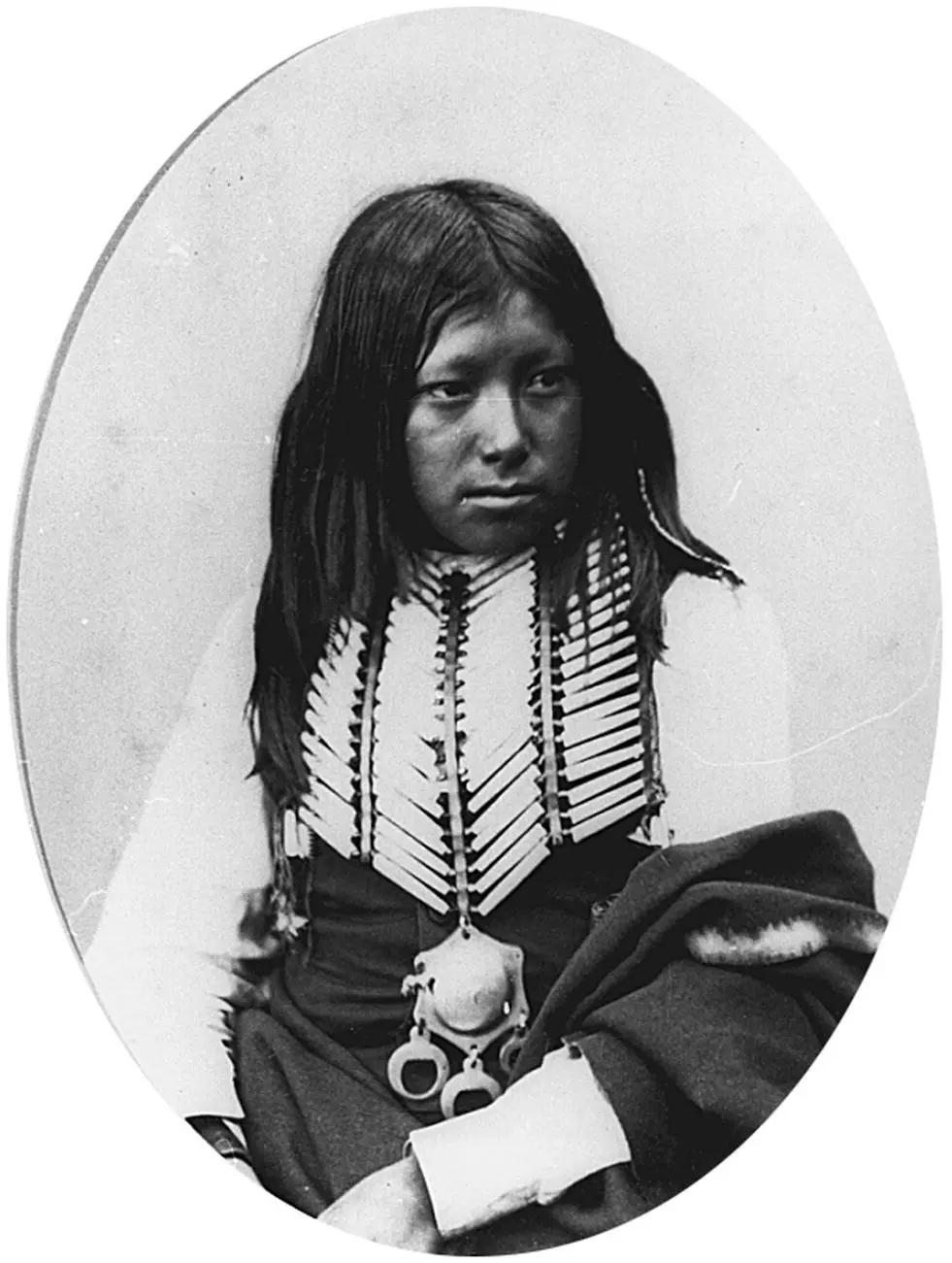

Figure 2.5 Buffalo Hump, Comanche Indian.

Source: Caldwell Papers, CN 10934, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Furthermore, in their struggle for survival, the Plains Indians during the eighteenth century escalated their reliance on women to achieve the suspension of hostilities with the Spaniards (as well as with competing Indian nations). During the 1770s and 1780s, the Comanche, Wichita, and other bands used captive Mexican women as hostages in their efforts to extract supplies and horses from the Spaniards or to propose political truces–sometimes in return for native women whom the Spaniards held hostage. The Plains Indians further utilized the time‐tested custom of having women, the traditional representatives of reconciliation, act as peace mediators in formal talks of conflict resolution. As noted, gender diplomacy anticipated kinship connections with adversaries and, subsequently, mutual commercial and defensive agreements. Given the disadvantages they faced on the hinterlands of their empire, the Spaniards readily accepted such arrangements.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, New Spain’s fear of the invasion of Texas by foreign powers diminished. The French threat to the province dissolved when, in 1762, France ceded Louisiana west of the Mississippi River to Spain during the War for the Empire, known in Britain’s New England colonies as the French and Indian War (1754–63), hoping to prevent the province from falling into British hands. Though the 5700 Frenchmen in Louisiana did not welcome the prospect of becoming Iberian subjects and sought to undermine Spanish rule by forcing their first Spanish governor to depart for Cuba in 1768, the next year, a Spanish fleet reestablished Spanish sovereignty over the new acquisition. The British settlements situated along the Atlantic Coast were too far away to cause many problems for Texas. And after 1783, even the new nation of the United States suffered from too many internal problems to pose much of a menace. It was the indios bárbaros who continued to present the pobladores and Spanish officials with the most immediate difficulty.

But dramatic changes, with potentially adverse implications for New Spain and its northern frontiers, were taking place in Spain under the new Bourbon king, Carlos III (r. 1759–88). An admirer of the Enlightenment philosophies then current throughout Europe, Carlos moved to bring about important reforms to make the Crown’s administration of the American colonies easier and to restore Spain’s diminished great‐power status. To Mexico, Carlos dispatched José de Gálvez to investigate the colony and recommend reform policy. Gálvez’s fact‐finding tour, which lasted from 1765 to 1771, produced a series of changes. The Crown replaced native Mexican lower‐level administrators (who allegedly were guilty of institutionalized graft, inefficiency, and flouting the laws) with trusted and efficient officers from Spain who would preside over intendancies, or districts, in the interest of better government. Other edicts lowered the amount of taxes but ensured their collection by an efficient corps not known for corruption, as the old tax collectors had been. Free trade was established in 1778 within most of the Spanish kingdom. Subsequent directives opened more New Spanish ports for trade and lowered custom duties to encourage intercolonial commerce. These “Bourbon” reforms brought about a fabulous development within the empire.

In the meantime, the king entrusted the Marqués de Rubí with carefully inspecting the military organization and the state of defenses of the Far Northern frontier. Rubí spent from 1766 to 1767 gathering information for his report, touring the frontier from the Gulf of California to East Texas. In the process, he entered Texas from San Juan Bautista, on the Rio Grande, first inspecting the fledgling presidio complex at San Sabá. From there, his party headed for San Antonio, then to Los Adaes, the designated capital of the province, and to other stations in East Texas, thence to La Bahía, and from there back to San Juan Bautista. After this 700‐mile swing, Rubí submitted his recommendations for presidial system reform.

Rubí’s recommendations laid the groundwork for the New Regulations of Presidios of 1772. In consideration of the post‐1762 conditions, in which Spanish‐owned Louisiana now shielded Texas from European enemies, the new regulations directed several maneuvers: pulling back the military and missionary presence in East Texas; the relocation of the settlers of East Texas to San Antonio, so as to strengthen the latter city (the provincial capital would also be moved to Béxar); and the implementation of a velvet‐glove policy toward the Comanches and other northern tribes and an iron‐fist one toward the Apaches. The last suggestion derived from Rubí’s understanding of Indian affairs. The Norteño attacks upon Spanish institutions were not directed at the whites specifically; instead, the Comanches and their allies sought retaliation for the Spanish practice of coddling, through missionization, their common Apache enemy. Rubí reasoned that peace in Texas might be achieved through an alliance with the Norteños against the Apaches, a partnership that (in addition to trade) the Norteños also desired.

Whereas the new policy against the Apaches alienated few Spanish colonists, such was not the case with the directives to uproot the people of East Texas. The East Texas pobladores living around the presidio and mission–approximately 500 persons, including Spaniards, Indians, blacks, and some French‐descent people who had transferred from Louisiana–were enjoying relative prosperity and had no wish to leave their homes. The governor of Texas, Juan María de Ripperdá, sympathized with the pobladores but had his orders to oversee the evacuation. In June 1773, the departure of 167 Los Adaes families, along with soldiers and friars, began. The group reached San Antonio after three months of suffering en route due to illness, floods, poor equipment, and few mounts. Within a few weeks after arriving in Béxar, some thirty Adaesaños had perished from the hardships they had endured on the march.

Once in San Antonio, the Adaesaños asked the governor for the right to return to their homes, which they already missed. The governor, still sympathetic to their situation, received their supplication without protest and gave them his personal approval to return as close to their former home sites as the Trinity River. Later, the viceroy approved the governor’s decision, as there now seemed to be a need to defend the East Texas region from land‐hungry British settlers pushing west.

A momentous march in the fall of 1774, led by Antonio Gil Ybarbo, who longed to return to his ranch, resulted in the founding of Bucareli on the Trinity River in September. Named after the viceroy, the little settlement increased in population (347 in 1777) but faced numerous problems, among them dismal harvests, rampant disease, and attacks by Comanches. Consequently, in the spring of 1779, some 500 people left Bucareli and pushed farther east, closer to where their homes had once been. Settling near the abandoned mission Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de los Nacogdoches, they founded a new town that they logically named Nacogdoches.

Nacogdoches survived to become the only successful civilian settlement in East Texas. Significantly, it owed its origins to actions other than those that had determined the establishment of San Antonio de Béxar and La Bahía. In violation of official settlement policy, the Tejanos had trusted their own instincts and successfully launched what is today one of the oldest municipalities in Texas history.

Читать дальше