Notwithstanding the tribulations on the eastern, northern, and western frontiers, the three civilian settlements in south‐central Texas that traced their origins to the 1710s remained in place as the nineteenth century dawned. San Antonio, now the provincial capital, had a population of 2500 near its chain of five missions and in the town of Béxar. Some 700 persons lived in Goliad’s surroundings, and about 800 lived in Nacogdoches. A few more pobladores populated two new towns established to counter the threat of Anglo American aggression from the United States: Salcedo, founded in 1806, was situated on the Trinity River, near the old outpost of Bucareli; and San Marcos de Neve, founded in 1808, was located north of today’s city of Gonzales. Neither community thrived. Salcedo’s population was listed as ninety‐two inhabitants in 1809, but no one lived there by 1813. San Marcos de Neve had a population of sixty‐one in 1808, but a flood in June of that year, followed by Indian attacks, persuaded the luckless settlers in 1812 to relocate.

Trade with other frontier areas remained brisk, giving a needed boost to the province’s fledgling market economy. Residents of Nacogdoches continued to violate government trade regulations, swayed by the demand for their goods east of the Sabine River; indeed, contraband trade seemed a necessary mode of survival for the isolated community. Natchitoches, Louisiana, was scarcely one hundred miles away, which seduced men like Antonio Gil Ybarbo, who carried on such a lucrative extralegal business that the government ultimately investigated and arrested him. Military troops dispatched to Nacogdoches in the mid‐1790s hardly discouraged the contraband ventures. Neither were commandants able to prevent foreigners from migrating into the area. Soon after its founding, Nacogdoches had a population composed of various ethnic groups engaged as merchants, Indian traders, and ranchers, many of whom took Spanish wives and acclimated themselves to Spanish‐Mexican culture. It was there that the only American trading company in Spanish territory functioned. With the endorsement of the royal government, the enterprise of Barr and Davenport, having commercial connections to close‐by New Orleans, sought to pacify the neighboring Indians and supply the needs of local soldiers.

For people in the interior, economic activity remained agrarian based, with ranching persisting as the most secure means of making a living. The business of trading horses and mules picked up within the province as well as between Louisiana and Texas during the 1770s, in part due to the success of the British colonies in their struggle for independence. Texas rancheros around San Antonio and La Bahía engaged in illegal intercolonial trade by exchanging their livestock for tobacco and other finished goods that made their way into Louisiana from the newly independent United States or from European countries. A new opportunity for those on the make appeared when the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France, a move that brought Anglo American settlers to the New Orleans region. The proceeds of clandestine commerce were not equitably distributed among all segments of Texas society, however, as the large rancheros were the primary beneficiaries.

The king had ever prohibited such international trade, but during the 1770s he passed decrees regulating access to wild herds (including the levying of fees upon those rounding up mesteño stock), cattle branding, and the exportation of livestock. Then he appointed governors who proved unduly strict in enforcing these laws. Furthermore, legal restrictions upon the rancheros and the reduction of the wild herds due to slaughtering and exportation by Tejanos produced economic difficulties, further angering the ranching elite. Over the years, the pobladores of Texas had developed an identity tied more to their daily necessities than to the imperial designs that the authorities sought to implement. During the colonial era, the Tejanos had survived almost on their own, living by their wits, ignoring the king’s decrees when they conflicted with immediate concerns. They had come to appreciate their semiautonomous relationship with the heartland, and now they resented what seemed an unnecessary intrusion into their personal affairs.

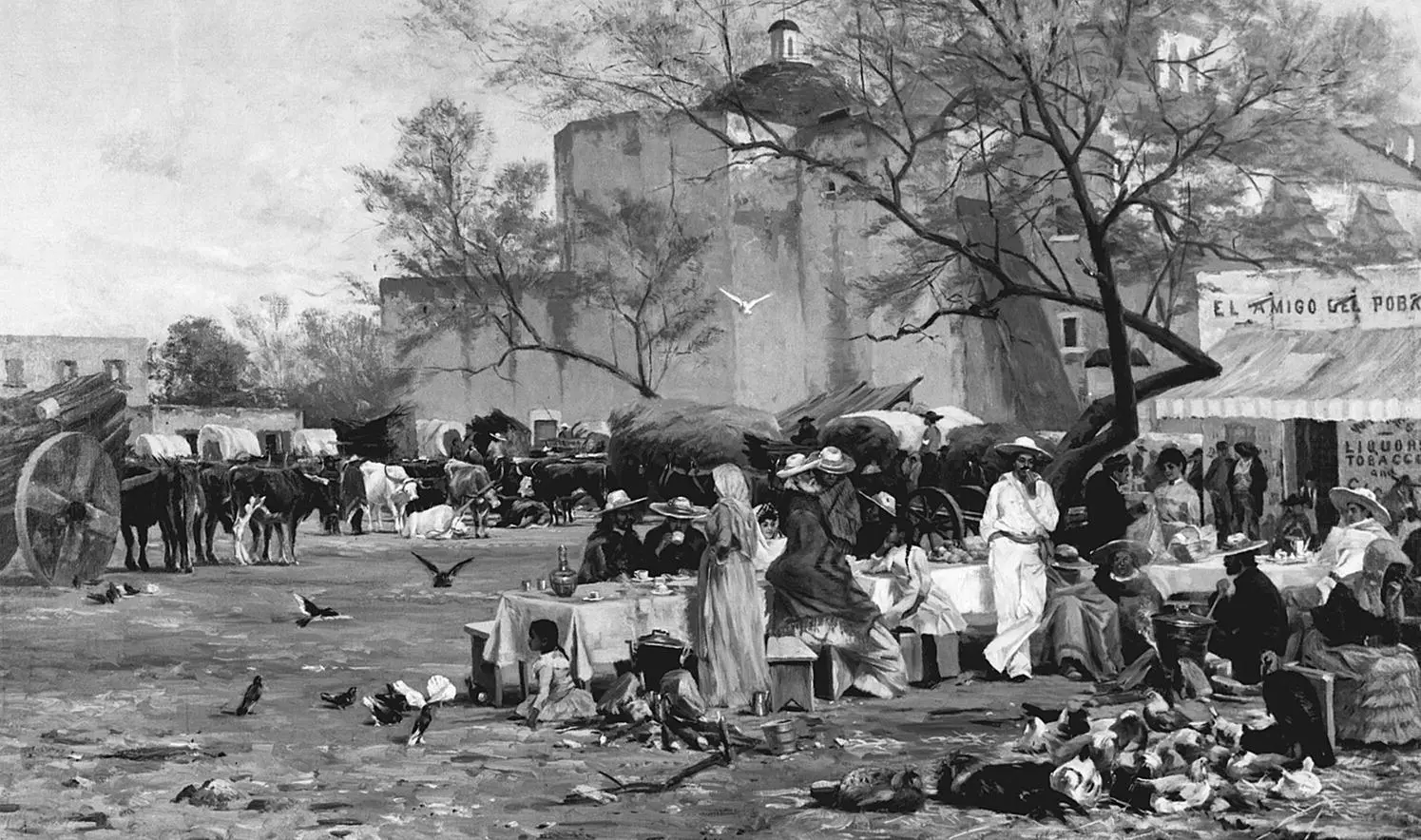

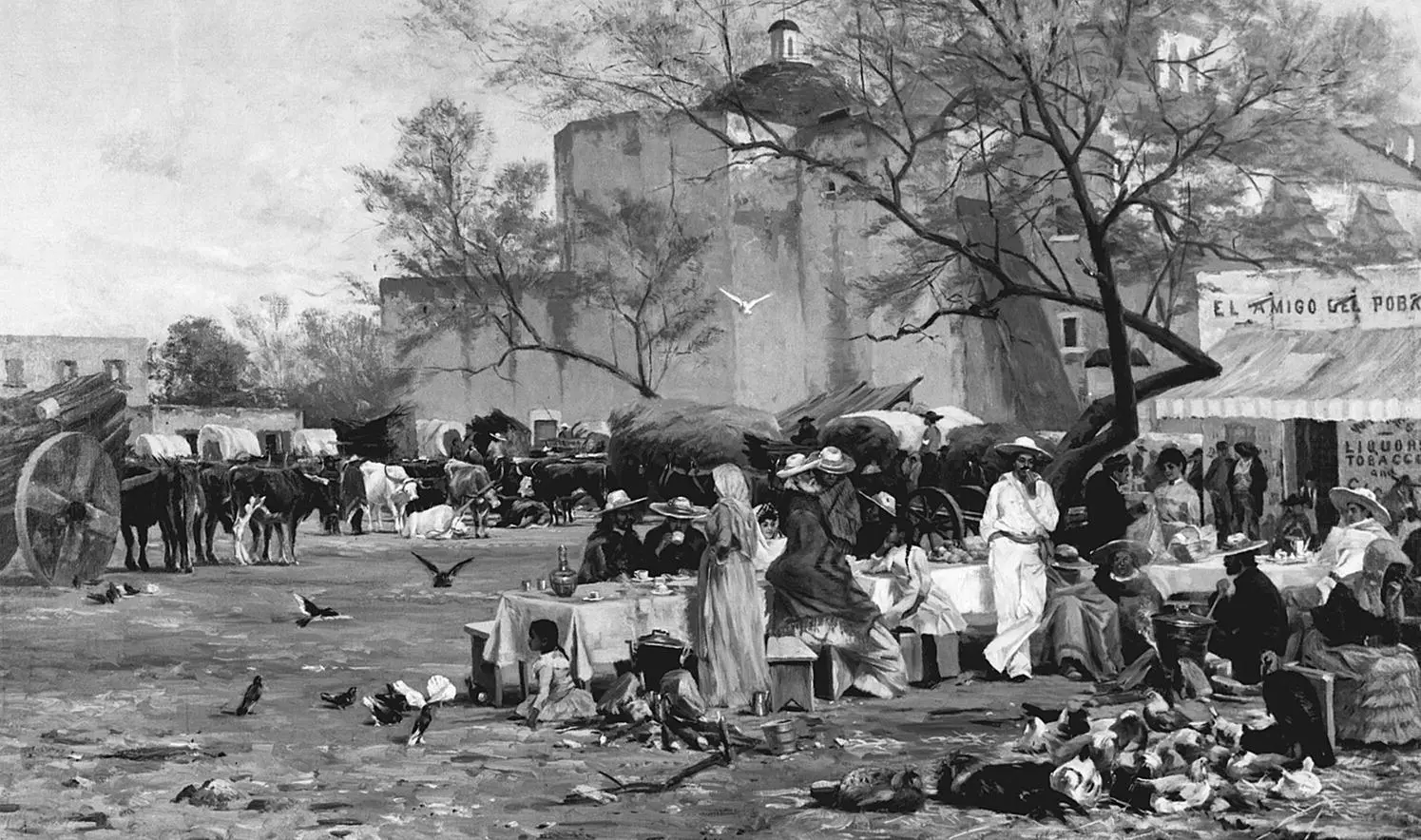

The Bourbon Reforms of the Enlightenment, which helped Spain make a remarkable recovery, produced resentment and discontent toward the mother country in New Spain. Over the centuries, Mexico had come to perceive itself as something greater than a mere colony. Thus, Mexicans resented the newly appointed peninsular administrators who practically monopolized the intendancy and tax‐collection positions enacted by the reforms. Furthermore, they disliked the arrogant attitudes of the peninsulares, who insisted upon deference and even subservience to their positions. Naturally, the people resented these developments, but vexation did not signify a wish to overthrow the system, rather a desire to replace a bad government that denied them full participation with a more democratic one ( Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 The marketplace was the center of life in frontier towns.

Source: Courtesy of the Witte Museum, San Antonio, Texas (#1936–6518 P).

It was, then, an imperial crisis that ultimately led the people of Mexico, already alienated by the Bourbon Reforms, to talk of doing something about their dependent status. Spain’s European wars after 1789 sapped the Spanish treasury, which in turn, exhausted the colonies; stepped‐up taxation and other forced contributions to the Crown produced financial distress throughout Spain’s New World holdings. Mexicans denounced the injustices but continued to pay homage to the king.

The drive for Mexican autonomy mounted following Napoleon’s conquest of Spain in 1808. Spaniards resisted the French occupation on May 2 ( Dos de Mayo ), then organized a Cortes (parliament) to hold the land while the deposed King Ferdinand VII remained in exile. Copying the Iberian example, the Latin American colonies established juntas (committees) to protect the New World empire until Ferdinand could reassume the throne.

In New Spain, criollos in Querétaro (in the state of Querétaro) established a similar junta. Most colonists had felt the pinch of Spain’s money‐raising measures during the era of the Napoleonic wars, among them a priest from Dolores, Guanajuato, named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. Suddenly exposed as a plotter to overthrow the peninsular officials who had been running Mexico since Napoleon’s invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, Hidalgo opted for a war against bad government. Skirmishes broke out in Hidalgo’s parish at Dolores on September 16, 1810 ( Diez y Seis de Septiembre ) and developed into the unexpected: a social revolution between the colony’s elite and the downtrodden lower classes, many of the former being the criollos who themselves had planned to gain their independence from the peninsulares.

The revolt rippled into far‐off Texas. Despite the distance between the core government and the frontier, the province was never so isolated that political winds blowing in the interior did not earn the notice of Tejanos. In Texas, one Juan Bautista de las Casas, a military veteran, took up Hidalgo’s grito (cry, or yell) for independence, garnering the support of some of the soldiers in the Béxar presidio, members of the lower class in the city, and local rancheros who had been alienated by recent Crown policies. On January 22, 1811, Las Casas displaced the few official representatives of royalist government still living in Béxar. From the capital, the insurrection widened to other parts of the province. But Las Casas’s rebellion had not gained the support of all Béxareños, and it soon encountered opposition from proroyalist forces in the city who ousted Las Casas on March 2, 1811. Given a trial in Coahuila, Las Casas received a death sentence and was shot in the back for treason; to remind would‐be rebels of the penalty for challenging the status quo, royal officials sent his head to Béxar for public display. Meanwhile, Father Hidalgo, who was defeated in battle on March 21, 1811, also suffered execution.

Читать дальше