1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...22 Often your feelings are simply due to a thought or memory that you may not even be totally aware of having had. Other times they can be symptoms of another disorder such as depression or anxiety problems (see Chapter 9for information about anxiety disorders and Chapter 12for more on depression). Some of the feelings you experience on waking are left over from dreams that you may or may not remember. As a rule of thumb, it pays to be somewhat sceptical about the validity of your feelings in the first instance. Your feelings can be misleading.

When you spot emotional reasoning taking over your thoughts, take a step back and try the following:

1 Take notice of your thoughts.Take notice of thoughts such as ‘I’m feeling nervous; something must be wrong’ and ‘I’m so angry, and that really shows how badly you’ve behaved’ and recognise that feelings are not always the best measure of reality, especially if you’re not in the best emotional shape at the moment.

2 Ask yourself how you’d view the situation if you were feeling calmer.Look to see if there is any concrete evidence to support your interpretation of your feelings. For example, is there really any evidence that something bad is going to happen?

3 Give yourself time to allow your feelings to subside.When you’re feeling calmer, review your conclusions and remember that it is quite possible that your feelings are the consequence of your present emotional state (or even just fatigue) rather than reliable indicators of the state of reality.

4 If you can’t find any obvious and immediate source of your unpleasant feelings – overlook them.Get into the shower despite your sense of dread, for example. If a concrete reason to be anxious does exist, it won’t get dissolved in the shower. If your anxiety is all smoke and mirrors, you may well find it washes down the drain.

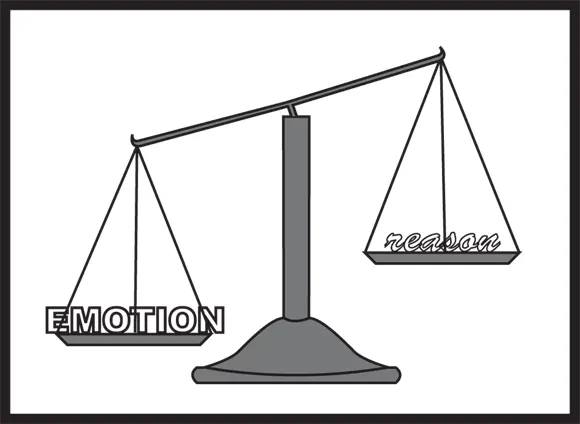

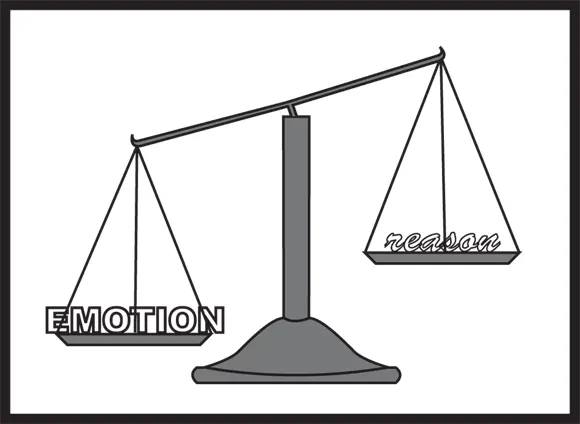

The problem with viewing your feelings as factual is that you stop looking for contradictory information – or for any additional information at all. Balance your emotional reasoning with a little more looking at the facts that support and contradict your views, as we show in Figure 2-5.

The problem with viewing your feelings as factual is that you stop looking for contradictory information – or for any additional information at all. Balance your emotional reasoning with a little more looking at the facts that support and contradict your views, as we show in Figure 2-5.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-5:Emotional reasoning.

Overgeneralising: Avoiding the Part/Whole Error

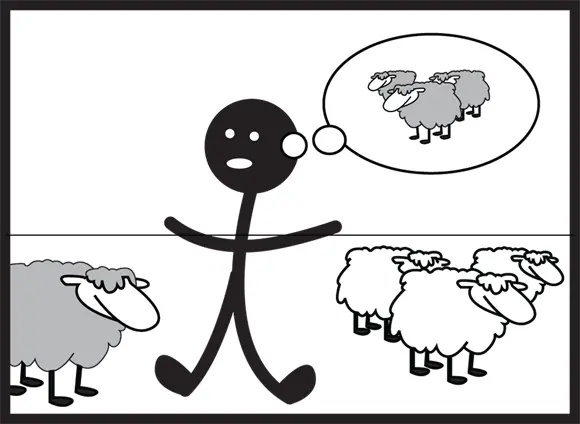

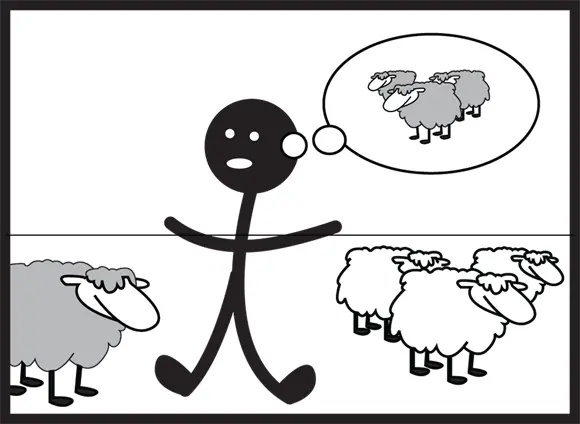

Overgeneralising is the error of drawing global conclusions from one or more events. When you find yourself thinking ‘always’, ‘never’, ‘people are …’ or ‘the world’s …’, you may well be overgeneralising. Take a look at Figure 2-6. Here, our stick man sees one sheep in a flock and instantly assumes the whole flock of sheep is black. However, his overgeneralisation is inaccurate because the rest of the flock are white sheep.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-6:Overgeneralising.

You might recognise overgeneralising in the following examples:

You feel down. When you get into your car to go to work, it doesn’t start. You think to yourself, ‘Things like this are always happening to me. Nothing ever goes right’, which makes you feel even more gloomy.

You become angry easily. Travelling to see a friend, you’re delayed by a fellow passenger who cannot find the money to pay her train fare. You think, ‘This is typical! Other people are just so stupid’, and you become tense and angry.

You tend to feel guilty easily. You yell at your child for not understanding his homework and then decide that you’re a thoroughly rotten parent.

Situations are rarely so stark or extreme that they merit terms like ‘always’ and ‘never’. Rather than overgeneralising, consider the following:

Get a little perspective. How true is the thought that nothing ever goes right for you? How many other people in the world may be having car trouble at this precise moment?

Suspend judgement. When you judge all people as stupid, including the poor creature waiting in line for the train, you make yourself more outraged and are less able to deal effectively with a relatively minor hiccup.

Be specific. Would you be a totally rotten parent for losing patience with your child? Can you legitimately conclude that one incident of poor parenting cancels out all the good things you do for your little one? Perhaps your impatience is simply an area you need to target for improvement.

Shouting at your child in a moment of stress no more makes you a rotten parent than singing him a favourite lullaby makes you a perfect parent. Condemning yourself on the basis of making a mistake does nothing to solve the problem, so be specific and steer clear of global conclusions. Change what you think you can and need to but also forgive yourself (and others) for singular errors or misdeeds.

Shouting at your child in a moment of stress no more makes you a rotten parent than singing him a favourite lullaby makes you a perfect parent. Condemning yourself on the basis of making a mistake does nothing to solve the problem, so be specific and steer clear of global conclusions. Change what you think you can and need to but also forgive yourself (and others) for singular errors or misdeeds.

Labelling: Giving Up the Rating Game

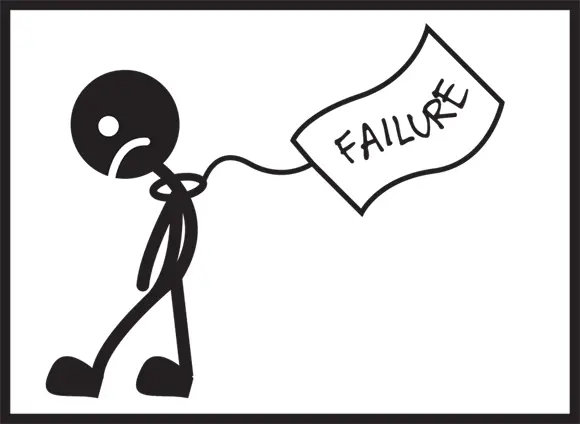

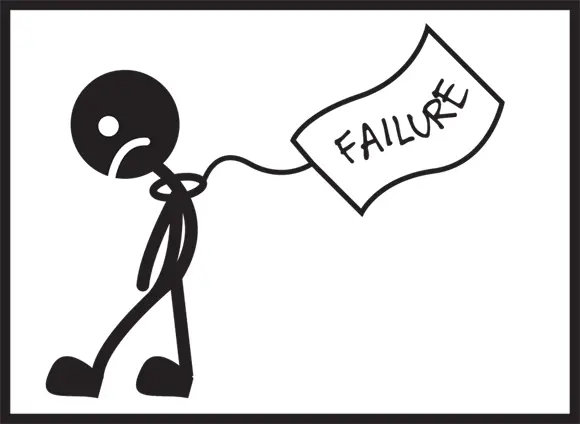

Labels, and the process of labelling people and events, are everywhere. For example, people who have low self-esteem may label themselves as ‘worthless’, ‘inferior’ or ‘inadequate’ (see Figure 2-7).

If you label other people as ‘no good’ or ‘useless’, you’re likely to become angry with them. Or perhaps you label the world as ‘unsafe’ or ‘totally unfair’? The error here is that you’re globally rating things that are too complex for a definitive label. The following are examples of labelling:

You read a distressing article in the newspaper about a rise in crime in your city. The article activates your belief that you live in a thoroughly dangerous place, which contributes to you feeling anxious about going out.

You receive a poor mark for an essay. You start to feel low and label yourself as a failure.

You become angry when someone cuts in front of you in a traffic queue. You label the other driver as a total loser for his bad driving.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-7:Labelling.

Strive to avoid labelling yourself, other people and the world around you. Accept that they’re complex and ever-changing (see Chapter 14for more on this). Recognise evidence that doesn’t fit your labels, in order to help you weaken your conviction in your global rating. For example,

Allow for varying degrees. Think about it: The world isn’t a dangerous place but rather a place that has many different aspects with varying degrees of safety and risk.

Celebrate complexities. All human beings – you included – are unique, multifaceted and ever-changing. To label yourself as a failure on the strength of one failing is an extreme form of overgeneralising. Likewise, other people are just as complex and unique as you. One bad action doesn’t equal a bad person.

When you label a person or aspect of the world in a global way, you exclude potential for change and improvement. Accepting yourself as you are is a powerful first step towards self-improvement.

When you label a person or aspect of the world in a global way, you exclude potential for change and improvement. Accepting yourself as you are is a powerful first step towards self-improvement.

Читать дальше

The problem with viewing your feelings as factual is that you stop looking for contradictory information – or for any additional information at all. Balance your emotional reasoning with a little more looking at the facts that support and contradict your views, as we show in Figure 2-5.

The problem with viewing your feelings as factual is that you stop looking for contradictory information – or for any additional information at all. Balance your emotional reasoning with a little more looking at the facts that support and contradict your views, as we show in Figure 2-5.