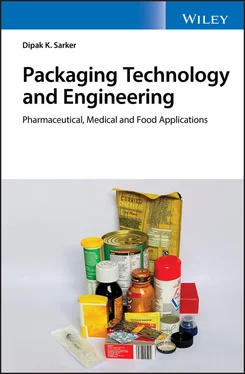

Central to the use of various types of packaging are the pivotal notions of their role (primary, secondary, and tertiary) and what type of environment might be appropriate for the packaging ( Figure 1.2). For example, plastic may be the best first choice but then, given the informing nature of the container, use of printed paperboard may present the best financial choice. The selection of packaging use is modelled against maintenance of standards, conveyance of identity, mechanical strength, product quality (both required and obtainable), and the purity required of the contained goods (particularly true of medicines). A good pack, therefore, needs to provide full information, be familiar or instantly recognisable, be based on a design for frequent or intermittent use (as required), and demonstrate suitability for its intended use. Additionally, where portioning of the product is required, such as multi‐vitamins, infant formula, dietary or meal replacements, or traditional pharmaceuticals, careful control of doses leads to medical and therapeutic compliance. Marketing and identity, aligned with matching product trends in pack volume, size, and form, are often indicators of product success. Because of the nature of the commercial sector packages need to be able to conform to high‐output manufacturing but also need some thought embedded in the design as a ‘superior’ quality product can have an associated cost. Reliable packaging universally prevents water and humidity breach and demonstrates mechanical resistance (shock, strength), chemical resistance (absorption; corrosion; air and gas exclusion; chemical, sterilant, or pH resistivity), microbial resistance, ease of handling, ease of repeated processing, and light exclusion. Regulation adherence of the materials used and framed pragmatically within the commercial goals of high‐numbered product sales must consider materials, product manufacture, and logistical cost – this usually means the pack should be lightweight, easily packed, and yet physically robust. The unit cost of the product given its manufacturing and shipping costs gives rise to the idea of lean manufacturing and cost trimming, some of which might arise from contact with a regular supplier and specific business approaches, such as just‐in‐time manufacturing.

In order to satisfy the requirements of intimate contact with the contents, all packaging should ideally be chemically inert, unreactive, non‐additive, non‐absorptive, and, therefore, does not add to or corrupt the pack contents. Additionally, the package is required by the manufacturer and customer alike to offer protection against deterioration and contamination during handling and transport. Storage and transport conditions are likely to vary considerably and will include alterations in freezer conditions, cold‐room conditions, and ambient or room temperature handling. Strict control of the physical and spatial separation of packs is needed during storage as this may encourage temperature and pressure gradients in the pack, possibly leading to weaknesses, pinholes, tears, and cracks. A regular part of the development of commercial products will, therefore, consist of inspections, history‐marking steps, label scrutiny, sampling procedures, establishment of non‐conformance or rejection criteria, record‐keeping for shipments, and product security during transportation and the distribution chain. As a ‘protector’ of the product within, the packaging has a key role in resisting physical impacts, such as is seen with perishables in the squashing, wetting, and bruising of shipped fruit. Packaging, therefore, allows for the product to reach the consumer in the most economical and ideal way possible despite the transit time and variable conditions experienced during shipment and storage. As a result of modern societal changes, including changes in family dynamics and time spent in traditional activities, such as cooking, there have been a number of changes required for commercial products, such as foods. Highly packaged goods are often preferred in modern times because people have less time to pursue ‘traditional’ preparatory activities in the household and there is a higher need for convenience but with the guarantee of safety and hygiene. Consequently, packaging consumption is higher in developed than in developing countries, the latter of which in turn consume more packaging than underdeveloped countries. This must be balanced against sociopolitical notions, such as global warming (from incineration and refining), recycling, and environmental pollution, which are more evident and higher on the political agenda in the developed world.

1.2.1 Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Packaging

Packaging type is classified into three rather subjective categories based entirely on their areas of use. Primary packaging (cf. sales packaging) is defined as the packaging that surrounds the product when sold to and received by the final consumer. In essence, it includes the packaging material substance or product that is in direct contact with the fill product and the other packaging components (i.e. lid, instructions). Secondary packaging, also referred to as group or grouping packaging, is packaging used to collate or hold together the primary packaging or units being sold and is used for ease of transportation. In modern times of global trade this can involve shipments back and forth across the globe. This process is undertaken by collecting the products together (e.g. a paperboard box holding blister trays of pharmaceutical pills or a corrugated cardboard box holding plastic laminated cartons of milk). Tertiary packaging is occasionally referred to as transport packaging and is needed to make convenient bundles of secondary packaged goods for mass transport or ultimate delivery of units or secondary packaging; it is used specifically to prevent physical damage that may occur during delivery (e.g. high‐density polyethylene [HDPE] skip or pallet). Recent studies based on damage to all transported foods, estimated at approximately 5–10% of all foods transported, demonstrate the value of primary and secondary packaging [4]. The term ‘unit load’ is often used to represent the packaging group consisting of the compounding together of more than one type of packaging for delivery processes and can be exemplified as the unit repackaged with stretch film on the palette. Consumer packaging is a term used to describe the packaging of a unit that reaches the final consumer from a retail outlet and this represents the received goods that make an impression on the consumer.

Identification of materials, such as plastics, that can be reutilised is an important part of the push for improved recycling. The three types of basic packaging – primary, secondary, and tertiary – encompass virtually all forms of containment ( Table 1.1), which often however possess different degrees of reusability. Primary packaging has a role in containing and protecting the commodity directly and is generally based on high‐purity materials; secondary packaging protects the integrity of the primary; and tertiary protects the secondary packaging and permits shipping and transportation of the primary and secondary products within the tertiary packaging. Consequently, secondary and tertiary packaging need lower levels of material purity and, therefore, may be more open to incorporation of recycled material. Occasionally, primary and secondary packaging are combined but they may also not have the same physical presence, for example shrink‐wrap (secondary) covering of a carton (primary); this is often used when the product cannot be easily corrupted by the carton. Primary packaging may be something like a sachet, a bottle, or a blister, which are often not accessible to current recycling practices. Secondary packaging is typified by a carton or a box and tertiary packaging is typified by a carton with an outer wrap. Tertiary packaging is typically a skip, drum, crate, etc. and represents containers that can make use of mixed aggregated recycled materials. The risk of primary packaging lies in its intimate contact with the product, which could be seen as a risk of product compromise and contamination. Typically this could involve the increasing loading of plasticiser or toxic materials in product contact packaging resulting from recycling. Chemical risk is less important in secondary packaging but significant risk arises from misleading information on the pack that could potentially cause injury to the recipient.

Читать дальше