In the modern era, that is, since the early 1900s, paper and cardboard have become extremely important packaging materials. Following the invention of plastics, the emerging industries making commercial packaging substituted plastic for paper as a primary packaging material. Many modern environmentalists hanker back to the times of the English Georgian and Victorian periods when forms of waxed paper were commonly used to wrap foods, such as cheese, butter, or meat, and pharmaceutical products, such as dried forms of poultices, pills ( comprimés ), and lozenges or oral dosage forms. A revolutionary step in packaging occurred in 1810 when Peter Durand, a British merchant, obtained a patent (UK no. 3372) for the first metal can. This can was for preservation packaging made from sheet metal to create a ‘cylindrical canister’. The actual invention of the ‘tin can’ is put down to Philippe de Girard of France, from whence the idea was taken up by Peter Durand. The idea of using hermetically sealed ‘canning’ containers, based on ab initio food preservation work in glass containers, had been proposed initially by the inventor Nicolas Appert in 1809. Appert's outstanding work, looking at increasing the nutritional and microbiological safety of foods, pioneered sterilisation technology and glass bottle preservation. Durand went on in 1812 to sell his patent to two entrepreneurs, Bryan Donkin and John Hall, who refined the process and product. Donkin and Hall established the world's first commercial canning factory in Southwark Park Road, London, UK. Unfortunately, the earliest tin cans were sealed by soldering based on a tin–lead alloy. A cumulative poisoning causing persistent ingestion did occur after a period owing to the toxic nature of the lead in the solder, which was particularly enhanced when the contents of the can were mildly acidic. As a result, a double‐seamed three‐piece can began to be used from 1900. In later times the lead‐based solder was replaced with arc welding of the sheet ‘tinplate’.

Tinplate became widely popular as it represented a stable, long‐lasting, and impenetrable means of packaging for foods. The choice of packaging used conveys information as to the value of the product. For example, since approximately 2015 (and unchanged as of 2019), and depending on the source, glass is valued at US$0.1–0.6/kg (recovered glass US$0.02/kg), aluminium is valued at US$2–4/kg, tinplate is valued at US$0.7–1.1/kg, and higher grade paperboard is valued at US$0.3–0.6/kg; these contrast with most routine polyolefins (cheaper plastics, such as polypropylene [PP] and polyethylene [PE]), which are valued at US$0.1–0.5/kg. Therefore, choosing glass, which is dense (2.5–3.4 times that of paper and plastic), with a prerequisite for a greater than 0.2 cm wall thickness for strength, in the modern era suggests a high‐value content since glass is both expensive and heavy and, therefore, has associated increased shipping costs. For many premium products the additional cost may be deflected by the large cost of the contents. For example, the cost of a can of green beans versus the cost of a bottle of champagne. In the former the can cost is approximately £0.02–0.05, whereas in the latter the bottle cost is approximately £0.50–1.00; this is because in the latter the contents cost at least 500 times more.

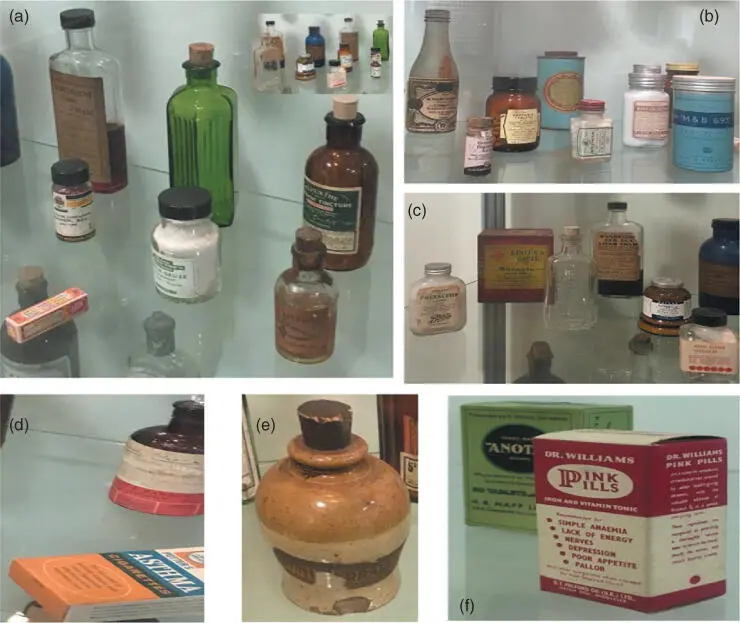

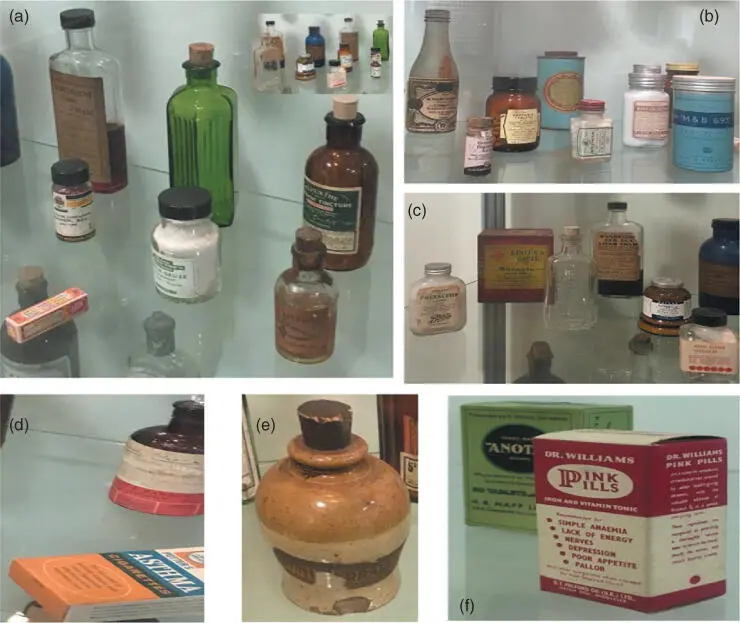

A series of different types of pharmaceutical packaging from across a 100 year period are shown in Figure 1.1. Amber glassware represents about 30% of medicine bottles. Modern medicine bottles are often fabricated from polyester tinted to mimic the old‐style amber glass bottles. A blue‐tinted bottle is shown in the insert in Figure 1.1a. Other forms of bottles, such as frosted or tinted vessels, were also used across products in the past; in modern times, these are used to aid product promotion. Figure 1.1b shows all‐aluminium screw‐top medicine cans that were used in the past but are used much less in the modern era. These have been superseded in many respects by the push‐out or ‘blister pack’ form of medicines. Figure 1.1c shows a very old cork‐topped bottle and a Victorian–Edwardian steel box for pills, which are practically never seen in the modern era, except for marketing promotions. Figure 1.1shows a range of mid‐twentieth century, Edwardian, Victorian, and earlier packaging materials used for medicines. The containers cover green chromium glass, iron oxide amber glass, flint glass, and other common forms seen more routinely today, such as paperboard cartons and aluminium closures. The ‘earthenware’ pottery vessel used in the past for medicine, milk, beer, and oil is rarely used in contemporary society but does find a place in speciality products as a marketing tool used to infer tradition and antiquity. Looking carefully at the range of packaging and comparing it with that seen customarily in pharmacies, artisanal, ‘24 hour’, and mini‐mart shops and supermarkets used mostly today there is a stark contrast and difference in Figure 1.1by virtue of the absence of plastic packaging in the period before 1950 [1].

Figure 1.1 Packaging of the past.

1.1.2 The Origins of Commercial Packaging

Andreas Bernhardt began wrapping products in paper and waxed paper for water retention stamped with his name and identification in Germany in 1551. Packaging uses and requirements have changed a lot in the modern era and most spectacularly over the last 150 or so years of purpose‐crafted commercial containment. The diversity of past packaging can be seen in Figure 1.1, with examples of flint, amber, green, and blue glass pharmaceutical sample bottles and a range of aluminium cans, paper, card, and pottery primary and secondary packaging. Some of the samples in Figure 1.1date from the 1960s and 1970s but others date back to the Victorian and Edwardian periods (1870s–1900s). The sometimes perceived as ‘modern‐era’ plastics industry actually started with John Wesley Hyatt, who invented modified cellulose in 1869, and, Leo Hendrik Baekeland, who invented resinous early plastic in 1907 in the USA. Other product examples include the ubiquitous tobacco snuff box (Mander Brothers) of the 1800s, the Beechams pills carton (UK) of the Victorian era in the 1840s, and the Lyons loose tea can (Ireland) and Laymon's aspirin tin (USA) of the Edwardian era in the 1900s. The more familiar forms of plastic containment that first appeared in the 1950s–1970s include the detergent and – the now infamous – mass‐produced carbonated drinks polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle. The tin can means of excluding air, light, and water for tea leaves is still used by many companies such as Jin Jun Mei (China), Whittard (UK), Tafelgut (Germany), and Twinings (UK), as part of a value‐adding marketing tool and for protection of delicate flavours and volatile oils. The sea‐change position of the use of tin‐plated steel (tinplate) and the tin can as a standard form of packaging will be discussed in Chapter 3.

1.1.3 Closures, Films, and Plastics

Rubber used in sealings and liddings became a mainstay of commercial packaging when, in 1849, Charles Goodyear and Thomas Hancock developed a method that destroyed the ‘tacky–sticky’ property of the material and added extra elasticity to natural rubber. In 1851 hard rubber, often referred to as ebonite, became commercially available in the Western world. A completely new revolutionary form of packaging was created in the invention of plastic. The innovative original artificial plastic was created by Alexander Parker in 1838 and was displayed at the Grand International Fair in London in 1862. This ‘parkesin’ rigid ‘resin’ was thought to be able to replace natural materials such as hardwoods and ivory. In 1892 William Painter patented the still ubiquitously used ‘crown cap’ closure (see Figure 3.3c) for bottles shaped from glass [1], which kept air (containing degrading oxygen) out and product flavours locked in. Also, in 1870 Hyatt took out a patent for ‘celluloid’ produced from cellulose in highly controlled conditions, under high pressure and temperatures. This created a polymer with low nitrate content for many different types of product wrappings. This discovery is now thought of as the first commercialised plastic and remained the only ‘plastic’ until 1907, when Baekeland produced ‘Bakelite’ (also spelt as Baekelite). Bakelite was universally used until the 1970s but was replaced by a new wave of plastics. A more exact understanding of plastics arose in 1920, when Hermann Staudinger's revolutionary idea was extolled and the notion of a plastic as a physical property rather than a chemical class came into fruition. All plastics, rubber, and cellulose are polymers or macromolecules but notably some do not show significant plasticity or deformability without brittle rupture. Staudinger's pioneering work concerning ‘polymer science’ was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1953.

Читать дальше