6 Crick FHC, Barnett L, Brenner S, Watts-Tobin RJ. 1961. General nature of the genetic code for proteins. Nature 192:1227–1232.

7 Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang R-Y, Algire MA, Benders GA, Montague MG, Ma L, Moodie MM, Merryman C, Vashee S, Krishnakumar R, Assad-Garcia N, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Denisova EA, Young L, Qi Z-Q, Segall-Shapiro TH, Calvey CH, Parmar PP, Hutchison CA III, Smith HO, Venter JC. 2010. Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome. Science 329:52–56.

8 Hershey AD, Chase M. 1952. Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. J Gen Physiol 36: 39–56.

9 Hug LA, et al. 2016. A new view of the tree of life. Nature Microbiol 1:16048. (Letter.) http://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.48

10 Hutchison CA III, Chuang R-Y, Noskov VN, Assad-Garcia N, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Gill J, Kannan K, Karas BJ, Ma L, Pelletier JF, Qi Z-Q, Richter RA, Strychalski EA, Sun L, Suzuki Y, Tsvetanova B, Wise KS, Smith HO, Glass JI, Merryman C, Gibs on DG, Venter JC. 2016. Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science 351: aad6253.

11 Imachi H, et al. 2020. Isolation of an archaeon at the prokaryote-eukaryote interface. Nature 577: 519–525.

12 Jacob F, Monod J. 1961. Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J Mol Biol 3:318–356.

13 Koonin EVE. 2015. Archaeal ancestors of eukaryotes: not so elusive any more. BMC Biol 13:84.

14 Lederberg J, Tatum EL. 1946. Gene recombination in Escherichia coli. Nature 158:558.

15 Leipe DD, Aravind L, Koonin EV. 1999. Did DNA replication evolve twice independently? Nucleic Acids Res 27:3389–3401.

16 Linn S, Arber W. 1968. Host specificity of DNA produced by Escherichia coli. X. In vitro restriction of phage fd replicative form. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 59:1300–1306.

17 Luria SE, Delbrück M. 1943. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 28:491–511.

18 Meselson M, Stahl FW. 1958. The replication of DNA in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 44:671–682.

19 Nirenberg MW, Matthaei JH. 1961. The dependence of cell-free protein synthesis in E. coli upon naturally occurring or synthetic polyribonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 47: 1588–1602.

20 Olby R. 1974. The Path to the Double Helix. Macmillan Press, London, United Kingdom.

21 Olsen GJ, Woese CR, Overbeek R. 1994. The winds of (evolutionary) change: breathing new life into microbiology. J Bacteriol 176:1–6.

22 Pace NR. 2009. Mapping the tree of life: progress and prospects. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:565–576.

23 Spang A, Saw JH, Jørgensen SL, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Martijn J, Lind AE, van Eijk R, Schleper C, Guy L, Ettema TJG. 2015. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature 521:173–179.

24 Schrodinger E. 1944. What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

25 Watson JD. 1968. The Double Helix. Atheneum, New York, NY.

26 Woese CR, Fox GE. 1977. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74:5088–5090.

27 Yang D, Oyaizu Y, Oyaizu H, Olsen GJ, Woese CR. 1985. Mitochondrial origins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:4443–4447.

28 Zinder ND, Lederberg J. 1952. Genetic exchange in Salmonella. J Bacteriol 64:679–699.

1 The Bacterial Chromosome: DNA Structure, Replication, and Segregation

1 DNA Structure The Deoxyribonucleotides The DNA Chain The 5′ and 3′ Ends Base Pairing Antiparallel Construction The Major and Minor Grooves

2 The Mechanism of DNA Replication Deoxyribonucleotide Precursor Synthesis Replication of the Bacterial Chromosome Replication of Double-Stranded DNA

3 Replication Errors Editing RNA Primers and Editing

4 Impediments to DNA Replication Damaged DNA and DNA Polymerase III Mechanisms To Deal with Impediments on Template DNA Strands Physical Blocks to Replication Forks

5 Replication of the Bacterial Chromosome and Cell Division Structure of Bacterial Chromosomes Replication of the Bacterial Chromosome Initiation of Chromosome Replication RNA Priming of Initiation Termination of Chromosome Replication Chromosome Segregation Coordination of Cell Division with Replication of the Chromosome Timing of Initiation of Replication

6 The Bacterial Nucleoid Supercoiling in the Nucleoid Topoisomerases

7 The Bacterial Genome

8 BOX 1.1 Structural Features of Bacterial Genomes

9 BOX 1.2 Antibiotics That Affect Replication and DNA Structure

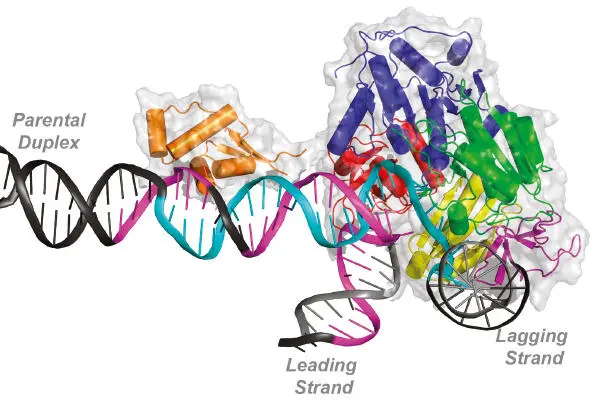

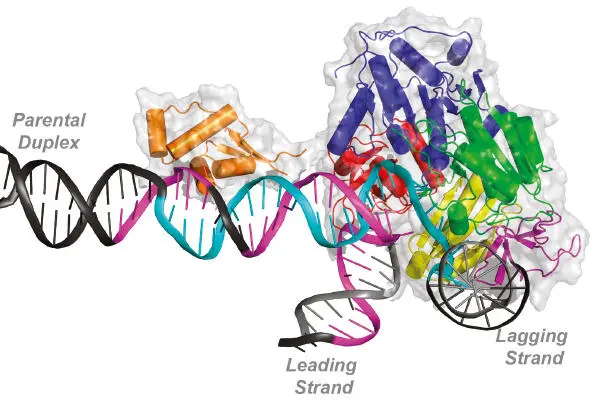

Model of the action of the PriA protein restarting a collapsed DNA replication fork. The DNA strands yet to be replicated (parental duplex) and the leading and lagging strands that have been replicated are labeled. The DNA strands shown in cyan and purple indicate regions that are believed to be bound by the PriA proteins based on biochemical experiments. The various subdomains of the PriA proteins are indicated in other colors. From Windgassen et al. (see Suggested Reading).

THE SCIENCE OF MOLECULAR GENETICS began with the determination of the structure of DNA. Experiments with bacteria and phages (i.e., viruses that infect bacteria) in the late 1940s and early 1950s, as well as the presence of DNA in chromosomes of higher organisms, had implicated this macromolecule as the hereditary material (see the introduction). In the 1930s, biochemical studies of the base composition of DNA by Erwin Chargaff established that the amount of guanine always equals the amount of cytosine and that the amount of adenine always equals the amount of thymine, independent of the total base composition of the DNA. In the early 1950s, X-ray diffraction studies by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins showed that DNA is a double helix. Finally, in 1953, Francis Crick and James Watson put together the chemical and X-ray diffraction information in their famous model of the structure of DNA. This story is one of the most dramatic in the history of science and has been the subject of many historical treatments, some of which are listed at the end of this chapter.

Figure 1.1illustrates the Watson-Crick structure of DNA, in which two strands wrap around each other to form a double helix. These strands can be extremely long, even in a simple bacterium, extending up to 1 mm—a thousand times longer than the bacterium itself. In a human cell, the strands that make up a single chromosome (which is one DNA molecule) are hundreds of millimeters, or many inches, long.

If we think of DNA strands as chains, deoxyribonucleotides form the links. Figure 1.2shows the basic structure of deoxyribonucleotides, called deoxynucleotidesfor short. Each is composed of a base, a sugar, and a phosphategroup. The DNA bases are adenine(A), cytosine(C), guanine(G), and thymine(T), which have either one or two rings, as shown in Figure 1.2. The bases with two rings (A and G) are the purines, and those with only one ring (T and C) are pyrimidines. A third pyrimidine, uracil (U), replaces thymine in RNA. The carbons and nitrogens making up the rings of the bases are numbered sequentially, as shown in the figure. All four DNA bases are attached to the five-carbon sugar deoxyribose. This sugar is identical to ribose, which is found in RNA, except that it does not have an oxygen attached to the second carbon—hence the name deoxyribose. The carbons in the sugar of a nucleotide are also numbered 1, 2, 3, and so on, but they are labeled with “primes” to distinguish them from the carbons in the bases ( Figure 1.2). The nucleotides also have one or more phosphate groups attached to a carbon of the deoxyribose sugar, as shown. The carbon to which the phosphate group is attached is indicated, although if the group is attached to the 5 ' carbon (the usual situation), the carbon to which it is attached is often not stipulated.

Читать дальше