Ya Yang - Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ya Yang - Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

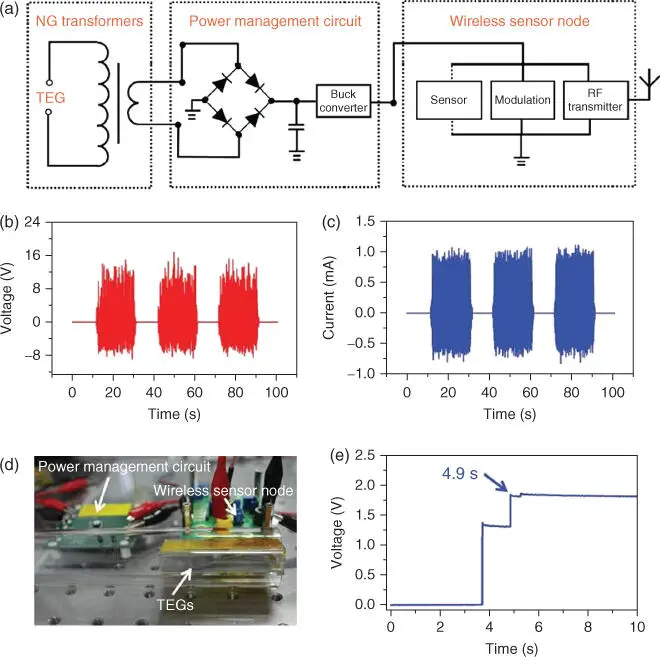

Figure 2.21The wind‐driven wireless sensor. (a) Schematic diagram of an integral powering circuit. The measured (b) regulative voltage and (c) the current at the transformer output port. (d) Photograph of the self‐powered system. (e) Output voltage of the system.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Wang et al. [33]. Copyright 2015, John Wiley and Sons.

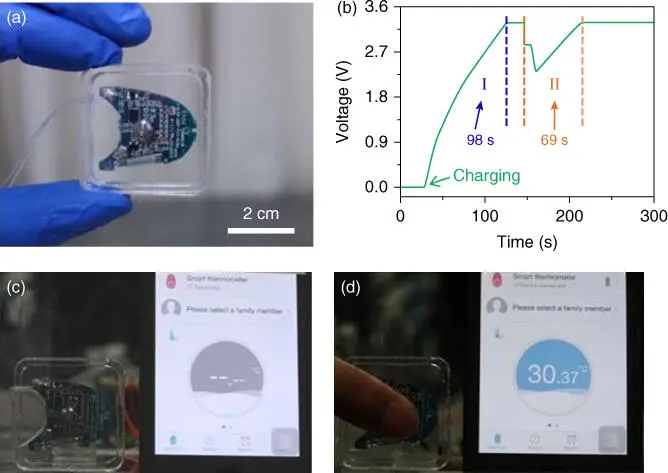

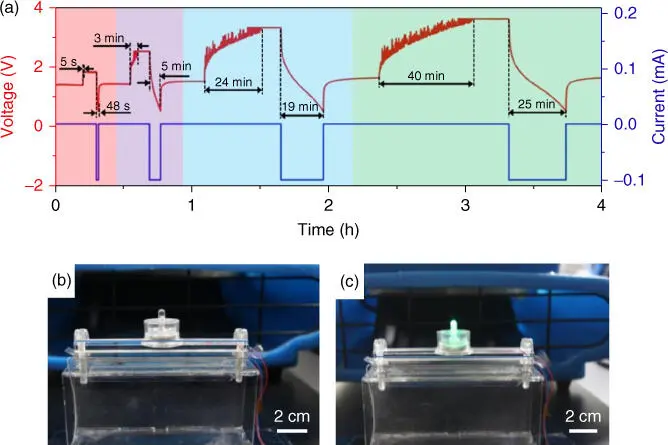

Zhao et al. fabricated a highly efficient TENG, which can harvest wind energy for sustainably powering a wireless smart temperature sensor node [61]. Figure 2.22a shows a photograph of the wireless temperature sensor. A 10 mF capacitor was used to store the energy from the nanogenerator. In the charging stage (process‐1), the capacitor can be charged from 0 to 3.3 V, as shown in Figure 2.22b. The voltage of the capacitor decreased when the sensor stood at the initial stage, and then increased due to the supplement from the nanogenerator. When the TENG was shut down, no electrical energy could be generated, resulting in no temperature data on the screen of the iPhone, as illustrated in Figure 2.22c. When the TENG was working, the temperature sensor can probe the temperature of a human finger, as shown in Figure 2.22d. Lithium ion batteries, which are most effective energy storage devices, have been widely used in numerous electronic devices Jiang et al. used the Li‐ion battery to store electrical energy generated by TENGs [69]. By adjusting the output voltage of the TENG via a power management circuit, the regulative electrical energy can be used to charge the Li‐ion battery, as shown in Figure 2.23a. It was found that voltages of the Li‐ion battery can be increased by increasing the charging time. The voltage of the battery was about 3.6 V, when charged by the TENG for about 40 minutes. Figure 2.23b shows a photograph of the fabricated self‐charging system, which consists of a TENG, a Li‐ion battery, and an LED. The LED can be lit up by the Li‐ion battery, which is charged by the TENG, as shown in Figure 2.23c.

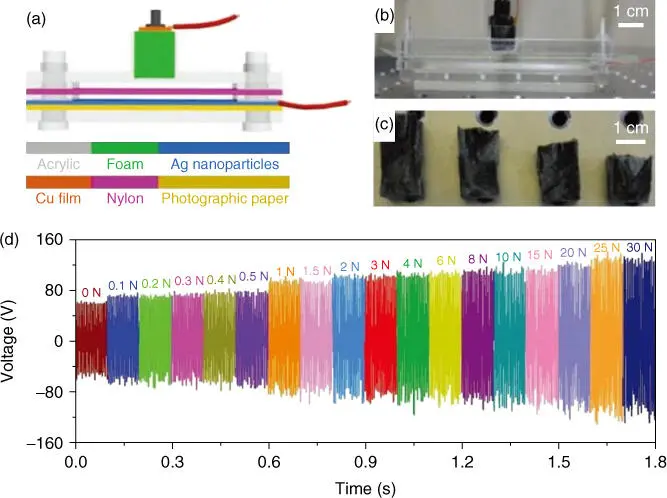

On the other hand, by integrating a WD‐TENG and a pressure‐sensitive elastic polyimide (PI)/reduced graphene oxide (rGO) foam, Zhao et al. fabricated a self‐powered pressure sensor [77]. Figure 2.24a shows a schematic diagram of the self‐powered pressure system. The TENG can generate output voltage signals by harvesting the wind energy. Figure 2.24b shows photographs of the self‐powered pressure system. Figure 2.24c presents four foams with different heights. The resistances of the elastic foam that was connected to the TENG can be changed with the diversification of the external forces, resulting in changes in the measured voltage, as shown in Figure 2.24d.

Figure 2.22The wind‐driven self‐powered wireless smart temperature sensor. (a) Photographs of the temperature sensor. (b) Charging curve of a capacitor by using the TENG with a PMC. Photographs of the temperature sensor before (c) and after (d) being powered by the TENG.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Zhao et al. [61]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society.

Figure 2.23The wind‐driven self‐charging Li‐ion battery. (a) Charging and discharging curves of the Li‐ion battery via the TENG. (b) Photograph of the self‐charging system. (c) Photographs of lighting up a green LED via the Li‐ion battery charged by the TENG.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Jiang et al. [69]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Figure 2.24The wind‐driven self‐powered pressure sensor. (a) Schematic diagram of the as‐fabricated self‐powered pressure sensor. (b) Photograph of the prepared pressure sensor. (c) Photograph of foams with heights. (d) The output voltage of the foam connected to the TENG.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Zhao et al. [77]. Copyright 2019, John Wiley and Sons.

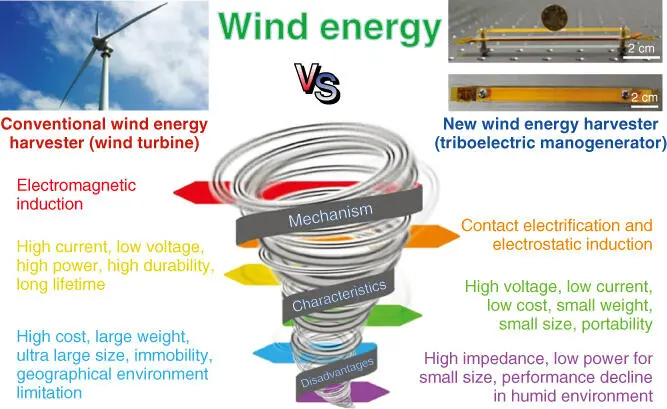

2.4 Comparison

With the fast development of modern industry, energy shortage has become an important problem that restricts the further development of the human society. Conventional wind harvesters based on the electromagnetic effect have been created as one of the most important ways for harvesting wind energy. Recently, TENGs based on the cooperation of the triboelectric effect and the electrostatic induction have been used to harvest wind energy. Figure 2.25shows the comparison between two wind harvesters, focusing on the mechanism, characteristics, and disadvantages [78]. Compared to conventional wind harvesters, TENGs can be considered as current sources with a large internal resistance, leading to characteristics of high voltage and low current. In addition, WD‐TENGs possess many advantages such as low cost, high efficiency, and easy fabrication, providing them the potential to be utilized as self‐powered electronics.

Figure 2.25The comparison between conventional wind harvester and new wind harvester based on a triboelectric nanogenerator.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Chen et al. [78]. Copyright 2018, John Wiley and Sons.

2.5 Conclusion

With the development of wearable electronics and wireless sensors, WD‐TENG, which can convert wind energy to electrical energy, are researched not only to enhance output performance but also to improve compatibility with other electrical devices. It has become a new trend in the further development of self‐powered devices that harvest energy from surrounding environment.

The theoretical models and working mechanisms of current WD‐TENGs have been described in this chapter. The output performances of the TENGs can be improved by optimizing advanced structures and materials. Among the several structures, vibrating plate‐based structure, elasto‐aerodynamics‐based structure, and rotary‐driven mechanical structure are three popular structures. Some advanced materials, such as cellulose, superhydrophobic surfaces, and nanowires, have been used. Lastly, soma smart self‐powered devices based on WD‐TENGs are introduced to present wide application prospects.

References

1 1 Wiser, R., Jenni, K., Seel, J. et al. (2016). Expert elicitation survey on future wind energy costs. Nat. Energy 1: 16135.

2 2 Mertens, S. (2003). The energy yield of roof mounted wind turbines. Wind Eng. 27: 507.

3 3 Grant, A., Johnstone, C., and Kelly, N. (2008). Urban wind energy conversion: the potential of ducted turbines. Renewable Energy 33: 1157.

4 4 Hameed, Z., Hong, Y., Cho, Y. et al. (2009). Condition monitoring and fault detection of wind turbines and related algorithms: a review. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 13 (1): 1.

5 5 Islam, M., Mekhilef, S., and Saidur, R. (2013). Progress and recent trends of wind energy technology. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 21: 456–468.

6 6 Henriques, J., Da Silva, F.M., Estanqueiro, A., and Gato, L. (2009). Design of a new urban wind turbine airfoil using a pressure‐load inverse method. Renewable Energy 34: 2728.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hybridized and Coupled Nanogenerators» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.