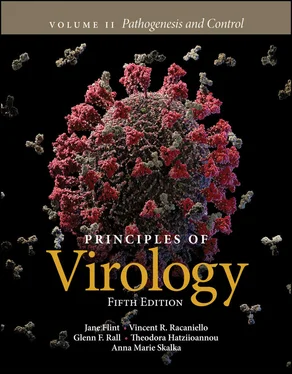

S. Jane Flint - Principles of Virology, Volume 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «S. Jane Flint - Principles of Virology, Volume 2» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Principles of Virology, Volume 2

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Principles of Virology, Volume 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Principles of Virology, Volume 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Volume I: Molecular Biology

Volume II: Pathogenesis and Control

Principles of Virology, Fifth Edition

Principles of Virology, Volume 2 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Principles of Virology, Volume 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Eyes

The epithelia that cover the exposed part of the sclera (the outer fibrocollagenous coat of the eyeball) and form the inner surfaces of the eyelids (conjunctivae) provide the route of entry for several viruses, including some adenovirus types, enterovirus 70, and herpes simplex virus. Every few seconds, the eyelid closes over the sclera, bathing it in secretions that wash away foreign particles. Like the saliva, tears that are routinely produced to keep the eye hydrated also contain small quantities of antibodies and lysozymes. Of interest, the chemical composition of tears differs, depending on whether they are “basal” tears produced constantly in the healthy eye, “psychic tears” produced in response to emotion or stress, or “reflex tears” produced in response to noxious irritants, such as tear gas or onion vapor. The concentration of antimicrobial molecules increases in reflex tears, but not psychic tears, underscoring the fact that host defenses are finely calibrated to respond to changes in the environment.

The primary function of tears is to wash away dust particles, viruses, and other microbes that land on the eye or under the eyelid. There is usually little opportunity for viral infection of the eye, unless it is injured by abrasion. Direct inoculation into the eye may occur during ophthalmologic procedures or from environmental contamination, such as improperly sanitized swimming pools and hot tubs. In most cases, viral reproduction is localized and results in inflammation of the conjunctiva, a condition called conjunctivitis or “pink eye.” Systemic spread of the virus from the eye is rare, although it does occur; paralytic illness after enterovirus 70 conjunctivitis is one ex ample. Herpesviruses, in particular herpes simplex virus type 1, can also infect the cornea, mainly at the site of a scratch or other injury, and immunocompromised individuals are at greater risk of retinal infection with cytomegalovirus. Such infections may lead to immune destruction of the cornea or the retina and eventual blindness. Inevitably, herpes simplex virus infection of the cornea is followed by spread of the virus to sensory neurons and then to neuronal cell bodies in sensory ganglia, where a latent infection is established. Injury to the eye that allows for viral entry need not be a major trauma: small dust particles or rubbing one’s eyes too aggressively may be sufficient to damage the protective layer and provide an opportunity for virus particles to access permissive cells.

While one may not normally think of eyelashes and eye brows as key components of host defenses, these well-placed patches of hair help to capture fomites that might invade the eye. An intriguing thought is that, as evolution progressed from apes to humans, dense hair was lost from all except a few parts of the body: on top of the head, in the pubic region, and around the eye. It is tempting to speculate that individuals who retained these patches of hair may have had an evolutionary advantage because they were more resistant to certain infections.

Urogenital Tract

Some viruses, including hepatitis B virus, human immunodeficiency virus type 1, and some herpesviruses, enter the urogenital tract, most typically as a result of sexual practices. Like the alimentary tract, the urogenital tract is well protected by mucus and low pH. The vagina maintains a pH that is typically between 3.4 and 4.5; when the pH increases toward neutrality (as a result of antibiotic use or natural changes in epithelial thickness during the menstrual cycle, for example), many pathogens, including bacteria and yeast, can flourish. Moreover, the vaginal mucosa is separated from the environment by a squamous epithelium that varies in thickness during the menstrual cycle, and that presents a formidable barrier to pathogens. In cases where this lining is thin, such as the zone between the endo- and ectocervix, viruses such as papilloma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 may be able to infect the epithelium and abundant CD4 +T cells beneath.

Sexual activity can result in tears or abrasions in the vaginal epithelium or the urethra, allowing virus particles to enter. Some viruses infect the epithelium and produce local lesions (for example, human papillomaviruses, which cause genital warts). Others penetrate deeper, gaining access to cells in the underlying tissues and infecting cells of the immune system (human immunodeficiency virus type 1) or the peripheral nervous system (herpes simplex virus type 2). Infection by the latter two viruses invariably spreads from the initial urogenital site to other tissues in the host, thereby establishing lifelong infections. Viral vaginitis (inflammation within the vaginal canal) can result from infection by herpes simplex virus type 2. This infection often causes painful lesions or sores, often visible on the vulva or the vagina, but occasionally found deeper in the vaginal canal. Because herpesviruses cannot be cleared from infected hosts, recrudescence can occur following stress, natural changes in the thickness of the canal during the menstrual cycle, or other infections. Herpes vaginitis could also affect the mouth and pharynx if oral sex is performed during a period in which virions are actively shed.

Viruses that gain entry by the urogenital tract are extremely common. Approximately one in six people between 15 and 50 years of age has genital herpes, and as this is a lifelong infection, the risk of transmission to sex partners is high. Herpesvirus infection is often asymptomatic, although the virus can still be shed and infect others. In pregnancy, infections by these viruses pose a particular risk to the developing fetus and can result in miscarriage, early delivery, or lifelong infection that begins in the neonate, dangers that can be mitigated by Caesarian delivery. Moreover, transmission of human papillomaviruses can result in genital warts and cervical cancer. Such viruses have a high transmissibility rate: there is a >20% chance that an uninfected individual will pick up the virus from an infected partner over a 6-month period. It is sobering to note that individuals may be affected by multiple sexually transmitted pathogens, and a preexisting infection with one may predispose to infection with another. For example, a genital herpes lesion provides an excellent portal for human immunodeficiency virus type 1.

Human semen is a particularly robust carrier of viruses: it is estimated that up to 27 distinct viruses can reproduce in, and be spread by, semen. These include viruses that are well known to be sexually transmitted, including human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and herpes simplex type 2, but also include emerging pathogens such as Ebola virus and Zika virus. Viruses such as influenza, dengue, and severe acute respiratory syndrome virus have been found in the testes, though it is not known if these viruses can be sexually transmitted. Even if these viruses are not sexually transmitted, their presence may nevertheless affect fertility, or increase the risk of acquiring a sexually transmitted disease. Some of these viruses, including the papillomaviruses, may even cause mutations in the DNA of sperm, which could then fertilize an egg and pass along the virus-induced mutations to future generations.

Placenta

A primary route by which a virus can be vertically transmitted from mother to offspring is to cross the placenta. Thus, in pregnant females, viremia may result in infection of the developing fetus. Maternal immune cells do not traverse the placental barrier, though these immune cells could bring virus into proximity with the placenta. Transplacental infections are distinct from perinatal infections, in which the virus is acquired via contact with maternal blood as the baby is delivered through the birth canal.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Principles of Virology, Volume 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Principles of Virology, Volume 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Principles of Virology, Volume 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.