S. Jane Flint - Principles of Virology, Volume 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «S. Jane Flint - Principles of Virology, Volume 2» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Principles of Virology, Volume 2

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Principles of Virology, Volume 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Principles of Virology, Volume 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Volume I: Molecular Biology

Volume II: Pathogenesis and Control

Principles of Virology, Fifth Edition

Principles of Virology, Volume 2 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Principles of Virology, Volume 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

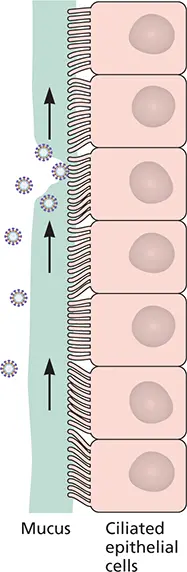

How deeply into the respiratory tract a virus penetrates is a direct cause of the kinds of disease that can result, analogous to the correlation of “infection depth” and systemic spread discussed earlier for skin infections. Viruses that reproduce in the upper respiratory tract (nasal passages, throat), such as rhinoviruses, typically tend to cause less severe infections than those that infect the lower respiratory tract, such as influenza virus and the coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Moreover, while some viruses, including those noted above, are typically restricted to the respiratory tract, others, such as measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella-zoster virus, use the respiratory tract as a portal to other tissues in the host, causing systemic diseases such as rashes ( Box 2.4).

Figure 2.7 Cilia help to move debris trapped in the mucus of the respiratory tract out of the body. Cells residing under the mucus have tiny, hair-like projections called cilia. Usually, the mucus traps incoming particles. In coordinating waves, often referred to as the “mucociliary escalator,” the cilia sweep the mucus either up to the nasal passages or back into the throat, where it is swallowed rather than in haled into the lungs. The acid of the stomach destroys most pathogens not inactivated by the mucus. An influenza virus particle is shown de grading the mucus layer to access the epithelial cells beneath.

Alimentary Tract

The alimentary tract is another major site of viral invasion and dissemination. Eating, drinking, kissing, and sexual contact routinely place viruses in the gut. Virus particles that infect by the intestinal route must, at a minimum, be resistant to extremes of pH, proteases, and bile detergents. Many enveloped viruses do not initiate infection in the alimentary tract, because viral envelopes are susceptible to dissociation by detergents, such as bile salts.

Figure 2.8 A picture is worth a thousand words. A group of applied mathematicians evaluated the distance and “hang time” of various-sized droplets produced after a sneeze, using the same strategies as ballistics experts studying gunfire. As many as 40,000 droplets can be released in a single sneeze, some traveling over 200 miles an hour. Heavier droplets (seen in the photo) succumb to gravity and fall quickly, while smaller droplets (less than 50μm in diameter) can stay in the air until the droplet dehydrates. Courtesy of CDC/Brian Judd/James Gathany, CDC-PHIL ID#11161.

As depicted in Fig. 2.4, the lumen of the alimentary tract, from mouth to anus, is “outside” of our bodies, and thus the anatomy of the alimentary tube possesses many features of the skin. Like the skin, the gut has physical, chemical, and protein-based barriers that collectively limit viral survival and infection: the stomach is acidic, the intestine is alkaline, and proteases and bile salts are present at high concentrations. In addition, mucus lines the entire tract, and the luminal surfaces of the intestines contain antibodies and phagocytic cells. Moreover, the small and large intestines are coated in a thick (50-μm) paste of symbiotic bacteria that not only aids in digestion and homeostasis but also imposes a formidable physical barrier for virus particles to access the cells beneath. As viruses make their way from mouth to anus, they are confronted with myriad obstacles that limit uptake. Interestingly, some intestinal microbes may actually facilitate viral infection ( Box 2.5).

Saliva in the mouth presents an initial obstacle to virus entry. While saliva is mostly water, it does contain lysozymes and other enzymes that aid in the breakdown of food but can also destabilize viral particles. One type of antibody found in saliva, secretory IgA ( Chapter 4), may directly bind and inactivate incoming viral particles. A protein known as salivary agglutinin has been reported to directly interfere with influenza virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1, possibly accounting for why ingestion is not the traditional route of infection by these viruses.

BOX 2.4

EXPERIMENTS

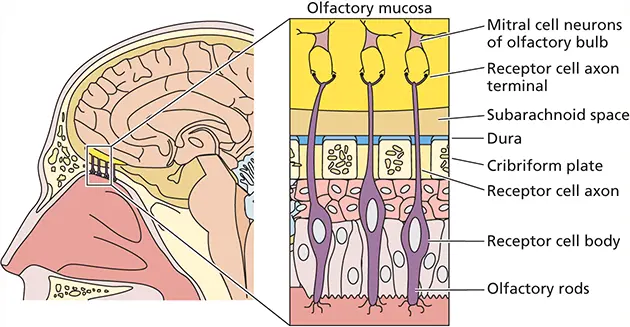

Olfactory neurons: front-line sentinels

Neurons within the olfactory mucosa are a potential entry point for respiratory viruses that can replicate in neurons, including measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella-zoster virus. Olfactory neurons are unusual in that their cell bodies are present in the olfactory epithelia and their axon termini are in synaptic con tact with olfactory bulb neurons. The olfactory nerve fiber passes through the skull via an opening called the arachnoid, and thus viruses that are present within the nasal mucosa are just one synapse away from the brain. Yet infections of the central nervous system (CNS) rarely occur. Why aren’t CNS infections more common via this route? Studies in mice have revealed some mechanisms that may prevent this potentially catastrophic outcome. Infection of mice with a neurotropic strain of influenza A Olfactory mucosa Mitral cell neurons of olfactory bulb Receptor cell axon terminal Subarachnoid space Dura Cribriform plate Receptor cell axon Receptor cell body Olfactory rods virus resulted in rapid apoptosis (cell suicide) of olfactory bulb neurons, coincident with activation of local phagocytes. Mice survived the challenge, raising the possibility that early activation of apoptotic pathways in olfactory neurons may prevent spread of influenza into the brain. Moreover, infection with both RNA and DNA viruses triggers the induction of long distance interferon signaling. Even in the absence of neurotropic virus infection, interferon stimulated proteins are synthesized in remote, posterior regions of the brain, activating an antiviral state and preventing further virus invasion.

Mori I, Goshima F, Imai Y, Kohsaka S,Sugiyama T, Yoshida T, Yokochi T, Nishiyama Y, Kimura Y. 2002. Olfactory receptor neurons prevent dissemination of neurovirulent influenza A virus into the brain by undergoing virus-induced apoptosis. J Gen Virol 83: 2109–2116.

van den Pol AN, Ding S, Robek MD. 2014. Long-distance interferon signaling within the brain blocks virus spread. J Virol 88:3695–3704.

BOX 2.5

EXPERIMENTS

Commensal bacteria aid virus infections in the gastrointestinal tract

Humans consist of at least as many bacterial cells as human cells; we are “metaorganisms.” Our gastrointestinal tract teems with bacteria, most of which aid in food digestion and promote health. Consequently, both our eukaryotic defenses and the commensal bacteria that occupy the intestine can be barriers to some viral infections.

In many cases, however, viruses have been selected that take advantage of commensal bacteria to facilitate viral infection of the host. For example, when the intestinal microbiota of mice was depleted with antibiotics before inoculation with poliovirus, an enteric virus, the animals were found to be less susceptible to disease. Further investigation showed that poliovirus binds lipopolysaccharide, the major outer component of Gram-negative bacteria, and exposure of poliovirus to bacteria enhanced host cell association and infection. Furthermore, the presence of bacteria also enhances infections by three other unrelated enteric viruses: reovirus, mouse mammary tumor virus, and murine norovirus. These results indicate that interactions with intestinal microbes can promote some enteric virus infections.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Principles of Virology, Volume 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Principles of Virology, Volume 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Principles of Virology, Volume 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.