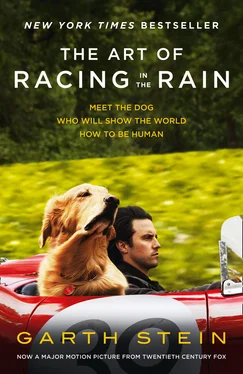

“Sweet dog,” she said to me. “Sweet dog.”

She returned to her preparations, pausing only occasionally to rub my neck with her bare foot as she passed, which wasn’t all that much, but meant a lot to me nonetheless.

I had always wanted to love Eve as Denny loved her, but I never had because I was afraid. She was my rain. She was my unpredictable element. She was my fear. But a racer should not be afraid of rain; a racer should embrace the rain. I, alone, could manifest a change in that which was around me. By changing my mood, my energy, I allowed Eve to regard me differently. And while I cannot say that I am a master of my own destiny, I can say that I have experienced a glimpse of mastery, and I know what I have to work toward.

9

A couple of years after we moved into the new house, something very frightening happened.

Denny got a seat for a race at Watkins Glen. It was another enduro, but it was with a well-established team, and he didn’t have to find all the sponsorship money for his seat. Earlier that spring he had gone to France for a Formula Renault testing program. It was an expensive program he couldn’t afford; he told Mike his parents paid for it as a gift, but I had my doubts. His parents lived very far away in a small town, and they had never visited in all the time I had been there. Not for the wedding, Zoë’s birth, or anything. No matter. Wherever the funding came from, Denny had attended this program, and he had kicked ass because it was in France in the spring when it rains. When he told Eve about it, he said that one of the scouts who attend these things approached him in the paddock after a session and said, “Can you drive as fast in the dry as you can in the wet?” And Denny looked him straight in the eyes and replied, simply, “Try me.”

That which you manifest is before you.

The scout offered Denny a tryout, and Denny went away for two weeks. Testing and tuning and practicing. It was a big deal. He did so well, they offered him a seat in the enduro race at Watkins Glen.

When he first left for New York, we all grinned at each other because we couldn’t wait to watch the race on Speed Channel.

“It’s so exciting.” Eve would giggle. “Daddy’s a professional race car driver!”

And Zoë, whom I love very much and would not hesitate to sacrifice my own life to protect, would cheer and hop into her little race car they kept in the living room and drive around in circles until we were all dizzy and then throw her hands into the air and proclaim, “I am the champion!”

I got so caught up in the excitement, I was doing idiotic dog things like digging up the lawn. Balling myself up and then stretching out long and thin on the floor with my legs straight and my back arched and letting them scratch my belly. And chasing things. I chased!

It was the best of times. Really.

And then it was the worst of times.

Race day came, and Eve woke up with a darkness upon her. A pain so insufferable she stood in the kitchen in the early hours, before Zoë was awake, and vomited with great intensity into the sink. She vomited as if she were turning herself inside out.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me, Enzo,” she said. And she rarely spoke to me candidly like that. Like how Denny talks to me, as if I’m his true friend, his soul mate. The last time she had talked to me like that was when Zoë was born.

But this time she did talk to me like I was her soul mate. She asked, “What’s wrong with me?”

She knew I couldn’t answer. Her question was totally rhetorical. That’s what I found so frustrating about it: I had an answer.

I knew what was wrong, but I had no way to tell her, so I pushed at her thigh with my muzzle. I nosed in and buried my face between her legs. And I waited there, afraid.

“I feel like someone’s crushing my skull,” she said.

I couldn’t respond. I had no words. There was nothing I could do.

“Someone’s crushing my skull,” she repeated.

And quickly she gathered some things while I watched. She shoved Zoë’s clothes in a bag and some of her own and toothbrushes. All so fast. And she roused Zoë and stuffed her little kid-feet into her little-kid sneakers and— bang —the door slammed shut and— snick, snick —the deadbolt was thrown and they were gone.

And I wasn’t gone. I was there. I was still there.

10

Ideally, a driver is a master of all that is around him, Denny says. Ideally, a driver controls the car so completely that he corrects a spin before it happens, he anticipates all possibilities. But we don’t live in an ideal world. In our world, surprises sometimes happen, mistakes happen, incidents with other drivers happen, and a driver must react.

When a driver reacts, Denny says, it’s important to remember that a car is only as good as its tires. If the tires lose traction, nothing else matters. Horsepower, torque, braking. All is moot when a skid is initiated. Until speed is scrubbed by good, old-fashioned friction and the tires regain traction, the driver is at the mercy of momentum. And momentum is a powerful force of nature.

It is important for the driver to understand this idea and override his natural inclinations. When the rear of a car “steps out,” the driver may panic and lift his foot off the accelerator. If he does, he will throw the weight of the car toward the front wheels, the rear end will snap around, and the car will spin.

A good driver will try to catch the spin by turning wheels in the direction the car is moving; he may succeed. However, at a critical point, the skid has completed its mission, which was to scrub speed from a car going too fast. Suddenly the tires find grip, and the driver has traction—unfortunately for him, with his front wheels turned sharply in the wrong direction. This induces a counterspin, as there is no balance to the car whatsoever. Thus, the spin in one direction, when overcorrected, becomes a spin in the other direction, and the secondary spin is much faster and more dangerous.

If, however, at the very first moment his tires began to break free, our driver had been experienced enough to resist his instinctive reaction to lift, he might have been able to apply his knowledge of vehicle behavior and, instead, increase the pressure on the accelerator, and at the same time ease out on the steering wheel ever so slightly. The increase in acceleration would have pushed his rear tires onto the track and settled his car. Relaxing the steering would have lessened the lateral g-forces at work. The spin would therefore have been corrected, but our driver would then have to deal with the secondary problem his correction has created: by increasing the radius of the turn, he has put himself at risk of running off the track.

Alas! Our driver is not where he had hoped to be! Yet he is still in control of his car. He is still able to act in a positive manner. He still can create an ending to his story in which he completes the race without incident. And, perhaps, if his manifesting is good, he will win.

11

When I was locked in the house suddenly and firmly, I did not panic. I did not overcorrect or freeze. I quickly and carefully took stock of the situation and understood these things: Eve was ill, and the illness was possibly affecting her judgment, and she likely would not return for me; Denny would be home on the third day, after two nights.

I am a dog, and I know how to fast. It’s a part of the genetic background for which I have such contempt. When God gave men big brains, he took away the pads on their feet and made them susceptible to salmonella. When he denied dogs the use of thumbs, he gave them the ability to survive without food for extended periods. While a thumb— one thumb! —would have been very helpful at that time, allowing me to turn a stupid doorknob and escape , the second best tool, and the one at my disposal, was my ability to go without nourishment.

Читать дальше

![Hubert Bancroft - The Native Races [of the Pacific states], Volume 5, Primitive History](/books/749157/hubert-bancroft-the-native-races-of-the-pacific-s-thumb.webp)

![Hubert Bancroft - The Native Races [of the Pacific states], Volume 1, Wild Tribes](/books/750126/hubert-bancroft-the-native-races-of-the-pacific-s-thumb.webp)