1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...18 The A-list map presents all the places that don’t need to be preceded by an apology: the high and mighty locations that know themselves to be the chosen ones. The map of B-list Britain—where I was born, raised and far prefer to live—covers everywhere else. When I’ve written travel features for the national press, it has always been about places that are firmly on the B-list: Birmingham, the Black Country, the East Midlands, Hull, Glasgow, various parts of Wales and Limerick in Ireland. The pattern has been the same every time. I submit my copy, and get a phone call or email a couple of days later suggesting that the feature needs a new introduction; something along the lines of ‘Well, you thought it was all a bit grim and rubbish, but—surprise!—there’s more to Blah than that these days.’ Sometimes they don’t even bother with the phone call or email, just add it as their own introduction, the generic view of B-list Britain as seen from the desk of a London hack. You see it even more graphically in the newspapers’ property pages: it’s cheap, but—oh dear—it’s Humberside .

Every country has its split, its Mason-Dixon Line; the British equivalent was always held to be one that connected the River Severn south of Gloucester with the Wash on the east coast. South of this diagonal lay the comparatively wealthy, Conservative-voting, whitecollar, Church of England part of the land; to the north, the poorer, Labour-voting, manual-working, nonconformist tribes. The line rippled in places, so that the southern tranche extended to Malvern and Worcester, around Warwick and Leamington Spa, and included the hunting country of Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland.

Growing up, it was a border I was acutely aware of, for I crossed it every day on the way to school. It was only a 25-minute train journey from Kidderminster to Worcester, but they were in different worlds. Worcestershire is an England-in-miniature in this regard: the county’s favoured images of orchards, cricket and Elgar belong entirely to its more upholstered, southern half. We in the northern triumvirate of Kidderminster, Bromsgrove and Redditch clung to the coat tails of the West Midlands and felt like scruffy gatecrashers in our own county. It was painfully evident at school, which drew its pupils from right across Worcestershire. The kids from Malvern and the Vale of Evesham had dads in Jags and strutted around the place as if they owned it, which they quite possibly do by now. There was never any doubt that they were several cuts above the far fewer of us who spilled off the train every day from Kidderminster, Stourbridge and Rowley Regis, with accents to prove it.

We even name our goods and companies keeping to the strict rules of the A- and B-list maps. This was something that hit me with a slap years ago in an airless undertaker’s parlour, where my mother and I were trying to sort out the arrangements for my grandfather’s funeral. With that sickly, faux-somnolent air they wear while thinking gleefully of all the noughts on your bill, the undertaker slid the catalogue of available coffins under our noses. They were all called the Windsor, the Oxford, the Canterbury, the Westminster and so on. Where, I wondered, were the Wolverhampton, the Barnsley or the Wisbech? Were Scots offered a Stirling or a Brechin in which to cart away their dearly departed?

A-list names conjure up the solid, dependable image that companies are desperate to tap into. Men’s products, in particular, mine the same seam repeatedly, whether in colognes called Wellington and Marlborough (but not, definitely not, Wellingborough), or the Crockett & Jones range of fine footwear—pick from, among others, Tetbury, Chepstow, Coniston, Brecon, Welbeck, Bedford, Chalfont, Pembroke or Grasmere. We buy insurance from Hastings Direct, rather than Bexhill Direct, where the company’s actually based, and smoke smooth Richmonds, not dog-rough Rotherhithes.

We map addicts are the oddest patriots. Maps bring out a curious British nationalism even in those of us normally allergic to displays of flag-waving. Wherever we go in the world, we pick up a local map and our very first thought is, ‘Hmmm, not as good as an Ordnance Survey.’ We feel sure, we know , that our maps are the finest the world has ever seen. Sneaking in there, too, is the certainty that the landscape they portray is also up there with the very best. We have neither very high mountains, nor very deep ravines nor very wild wildernesses, but the scale—like our climate—is modest and comforting, and the scenery often extremely lovely. And all of it so beautifully mapped.

It’s a force that mystifies me, while still it engulfs me: in absolutely no other aspect of life do I feel so resolutely, determinedly, proudly British. I’ve never voted Conservative (or, God help us, UKIP), bought the Daily Mail , sung ‘Rule Britannia’, stood in a crowd to wave at royalty, watched The Last Night of the Proms with anything other than incredulity or so much as cracked a smile at Last of the Summer Wine . Nearly a decade of living in Welsh-speaking Wales has brought me to the view that the UK as a nation-state might well have had its day, and the sooner we realise it, the better all round. And yet, open up an OS, a Bartholomew, a Collins or even—if nothing else is available—an AA road atlas that cost £2.99 from the all-night garage, and something deep within me trembles. That familiar layout and colouring, those tantalising names and the histories they hint at, the shape of those cherished coasts, the twisting tracks and roads, the juxtaposition of the great conurbations and the wild, empty spaces: a few minutes staring, once again, at the map of this island, or any part of it, and I’m stoked up with a love and a loyalty that knows no reason and no limit.

You have to be careful, though. Not only are there the siren warnings of the pioneers who have gone before, and ended up as wizened, cranky obsessives, but such certainty about British superiority can manifest itself in some pretty strange attitudes, if allowed to seep off the map shelf and into almost any other area of life. Britons are routinely encouraged to cling to the idea that they are, inherently, the best at anything, and if not the best, then at least the most worthy, noble or underrated. And if we can’t be that, we’d rather be the absolute worst: cosmically hopeless, the Eddie the Eagle among nations, usually coupled with a graceless sneer when we lose: ‘Pfft, well, we never wanted it, anyway.’ Rarely are we either the best or the worst, but it’s our actual position of mid-table mediocrity that we struggle hardest to cope with.

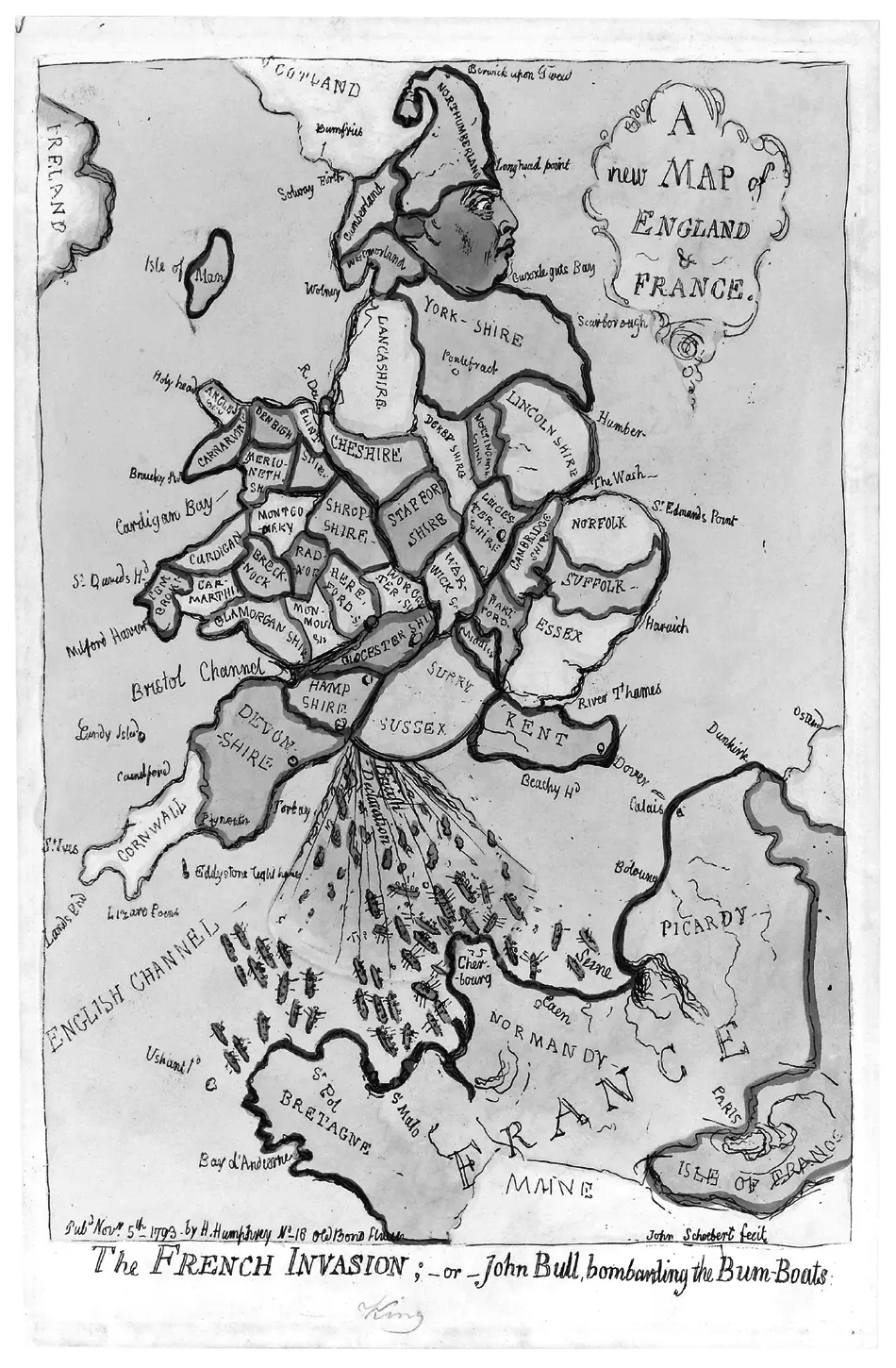

Though not when it comes to our maps: even Johnny Foreigner grudgingly admits that we’re still world-beaters in cartography. There is no other patch of land on the planet that has been as comprehensively, and so stylishly, measured, surveyed, plotted and mapped as the 80,823 square miles of Great Britain. We might have been late starters in the game, but we’ve more than made up for it subsequently, especially over the past four hundred years—ever since, in fact, we started needing maps in order to go and rough up bits of the rest of the world and declare them to be ours. Again, this is the perverse dichotomy of the British map aficionado: were it not for the Empire and our military bravado, we would be a great deal further down the cartographic rankings. It’s a dilemma to wrestle with, for sure, but boy, are we grateful for the maps.

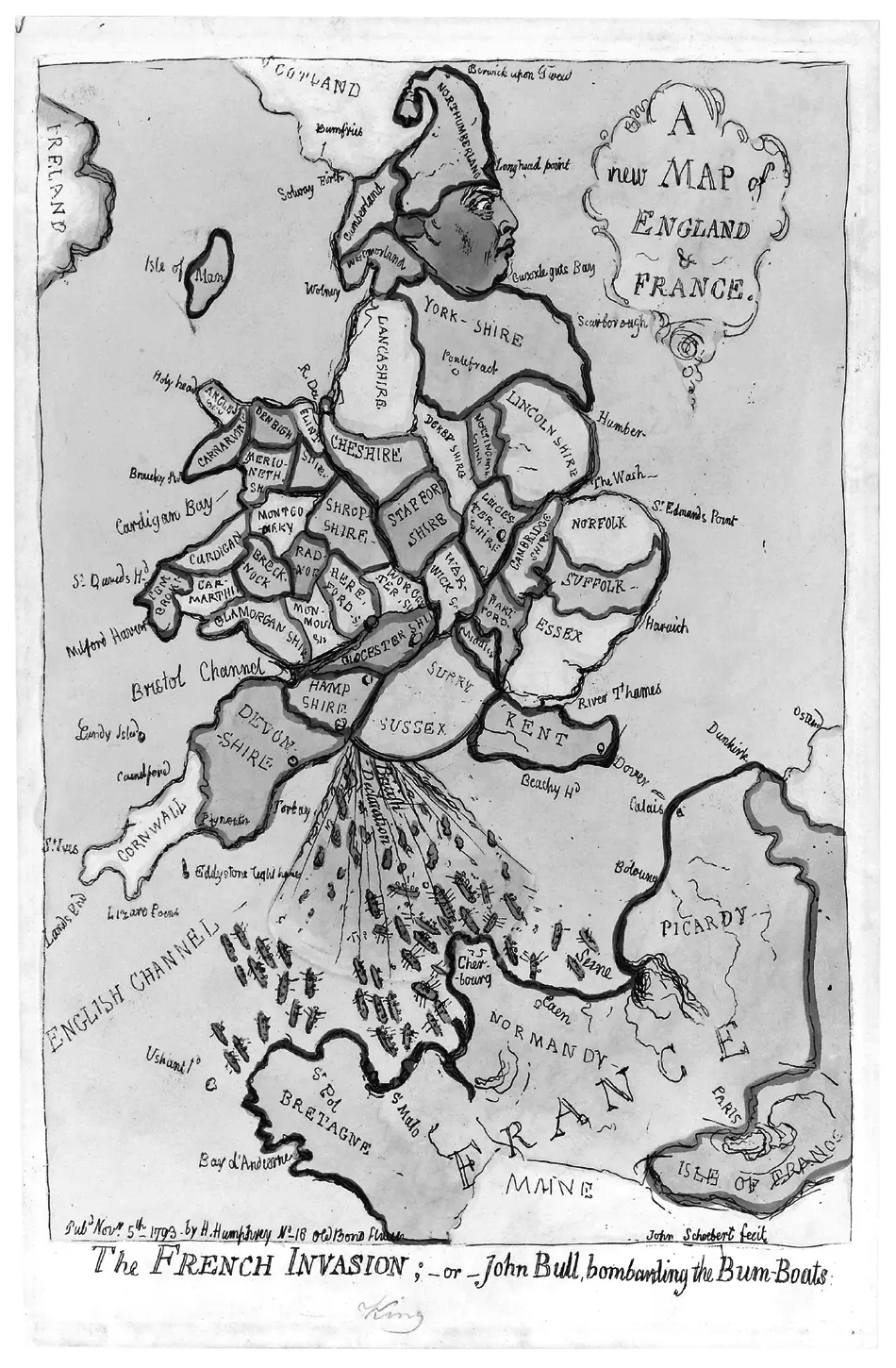

James Gillray’s map of England as King George III, crapping ‘bum boats’ into France’s mouth

Читать дальше