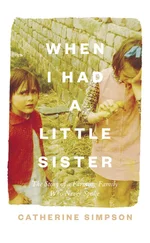

It was not going in my bedroom because it would get ruined. It was too good, my mother said. It was too good to get scribble gouges and felt-pen marks and cup rings on it. The mahogany desk was going in the sitting room and that was that.

Occasionally over the years I would turn the brass knob on the sitting-room door and push the door over the thick carpet and stare at the mahogany desk wedged between the grand piano and Tricia’s Edwardian sofa. It was a long way away; acres away over the swirling turquoise and gold carpet and flanked by tarnished photograph frames and piles of sheet music and china vases that I wasn’t allowed to touch either. It was far, far away – much farther away than it had been in Old Jack’s living room. It was not covered in scribble gouges or felt-pen marks or cup rings. It was not ruined, but its secret drawer was never opened and no one ever stroked its frayed leather top. No, the mahogany desk may not have been ruined but it was dusty and fading and empty of chocolate and so far away it was lost to me.

One way or another there seemed to be a lot of death about as we grew up – Old Jack, Great-Great-Aunt Alice, Grandad, endless farm cats, sickly piglets and occasional calves born dead, which is possibly why I was obsessed with ghost stories – tales of people coming back, people who were dead but not truly gone. I read and reread Aidan Chambers’s Ghost Stories and More Ghost Stories and, when all else failed, my Sunday-school prize, Saints by Request .

One afternoon Wuthering Heights came on the television. Mum said, ‘You might like this, it’s a ghost story.’ I watched, enraptured by Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier. The following day Mum went specially to John Menzies in Preston and bought me the book. I was ten years old and sat on the hearthrug doggedly reading it although I did not understand many words and had to skip Joseph and his broad Yorkshire dialect altogether (even though Joseph was basically Gran). Over several evenings I immersed myself in the passion and the brutality, the obsessive revenge, the jealousy and the violence of a story about a girl called Cathy that took place largely in a Northern kitchen. Mum recalled me finishing the book, turning to the front, reading the introduction, asking ‘What’s incest?’ (pronounced in-kest ), getting no answer and starting the book again. This was a wild world where life and death were close to each other; where it was better to commune with somebody even if they were dead than not commune with them at all.

Elizabeth, Tricia and I attended a Church of England primary school and we regularly went to Sunday school at the village church. Sunday school mainly consisted of Mr Herbert, the vicar (or ‘parson’ as my father called him), reminiscing about being bombed in Coventry during the Second World War and did not seem to have much to do with God – or at least did not address the interesting questions like did God really look like Old Jack and where, exactly, was heaven.

As a child I did not think to question the existence of God and took comfort in both the idea of a Gentle Jesus Meek and Mild Looking Upon this Little Child, and the vague notion of a heaven – which, I supposed, hovered somewhere or other full of all the dead people and animals I had ever known. At Christmas, God and Father Christmas became rolled into one – a jolly-faced old man who knew exactly what you’d been up to. The Father Christmas version of God was more worrying than normal-God because he could punish you by failing to bring the selection boxes, talc and bath-cube sets and embroidered hankies that appeared under the tree every year.

My Aunty Dorothy gave me a white King James Bible when I was confirmed aged ten which contained photographs of the Holy Land; of barren rocks, entitled In the Wilderness , and silhouettes in a boat upon sparkling water, called Fishermen on the Sea of Galilee – photographs I half-believed were taken in the time of Jesus Christ himself. There was also a ‘Births, Deaths and Marriages’ section for me to fill in. I was proud of my Bible and found it considerably more interesting than the Book of Common Prayer I received at the same time. I noticed there was a chapter in the Bible that was never mentioned at school or Sunday school – the Revelation of St John the Divine. I wondered if perhaps the vicar didn’t want to jump ahead and spoil the end of the story.

I asked my mother what it was like when we were dead. She said, ‘Ask Mr Herbert.’ Mr Herbert had white hair that stood on end and waved like a dandelion clock, he wore thick black-rimmed glasses and a dog collar and his hands shook. I once met him on the way back from a trip to the grocer’s. He was carrying a wicker basket in which a lone half-sized tin of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce rolled forlornly back and forth.

Mr Herbert came to school every Friday to tell us a story from the Bible but he did not engage in casual conversation with the pupils so I did not feel able to ask him anything. Instead I made up my own idea of heaven and decided heaven was a party in the village hall. I pictured the wooden chairs lined up around the edge of the dance floor, George the disc jockey getting his records ready, unseen ladies in the kitchen cutting sandwiches, arranging slices of Battenberg cake and over-diluting orange juice, the coloured lights glowing and the disco ball throwing sparkles hither and thither as it gently rotated – just like before the annual children’s WI Christmas party, in fact. But, this being heaven, it was a party only for the dead. Early doors Old Jack was there by himself but by the end of the 1970s all the empty spaces on the ‘Deaths’ page in my Bible were complete and the party was in full swing.

One night lying in bed in our freezing bedroom I asked Elizabeth whereabouts in the sky this heaven might be and she said, ‘Guess.’ I pointed up into the blackness somewhere over the milking parlour. ‘Nope,’ she said, pointing over the back garden towards the hen cabins, ‘other way! I win! That means you’ve got to get out of bed to put the light out!’

As a child there were a lot of people in my world and many of them were old.

I remember the moment I realized not everyone lived a life like mine, not everyone lived on a farm or even in a village. I was three or four years old and standing on the pavement in the local town waiting for the Whit Monday parade. Crowds two or three deep waited for the marching bands, the floats covered in crêpe paper and the festival queens with their retinues from all the surrounding villages – but I faced away from the road and stared at the toy-town houses behind me. I could tell they were tiny even though my head barely reached the door handles.

These houses were not like farmhouses; their front doors opened onto a pavement not a garden path or a farmyard, they had windowsills that I – somebody who didn’t even live there – could sit on, and they had windowpanes that I could press my forehead against and see right through. I stared harder. Yes, I could definitely see somebody’s ornaments and their settee and their fireplace.

Everybody I knew lived on a farm, usually down a long lane, surrounded by fields and woods and ponds and a yard and a garden and an orchard. Nobody could sit on our windowsills or look through our windows at our ornaments or our settees or our fireplaces.

‘Turn round,’ my mother said. I didn’t. I kept staring. Were these houses for old people, people who couldn’t walk and who sat in armchairs all day, like Old Jack? They couldn’t be for children, surely; not children like me and my sisters and my gaggle of cousins who could run as hard as we liked for as long as we liked and still not reach the neighbours.

Читать дальше