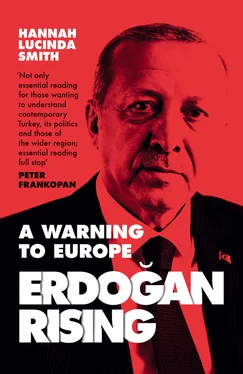

To write – and to live – under Erdoğan’s tightening authoritarianism is to cohabit with a voice in your head that asks Are you sure you want to say that? every time you press send on an article or crack a joke with a stranger. It is to see your tendency for social smoking soar into a daily, furtive habit that you indulge by the window late at night, and then to look in the mirror in the morning and realise that the faint worry line between your eyebrows is setting into a deep crevice. Dictatorship screws with your sex life; it makes you go through an internal checklist on every person you meet – what are they wearing? Where are they from? Who do they work for and how far can I trust them? I hear my neighbours rowing more often these days, witness more fights breaking out on Istanbul’s streets. The Turks who love the way things are going like to rub it in everyone else’s face. The Turks who hate it usually spill everything to the Westerners they meet – some of the few safe sounding boards they have left. Conversations that start with ‘How long have you lived in Turkey?’ usually come round to ‘Why on earth do you still stay?’ The stress of wondering if your phone is tapped and your flat being watched slows down your brain, becomes a tiring distraction, while at some point, you realise that all your conversations with friends come back to politics, and that although there is plenty of material for cynical, satirical humour none of it makes you feel much better once you’re done laughing. To live in this system is to watch people you know be seduced by power and money, and happily throw away their moral compass as they pursue them. It is to suck up to people you despise because in order to survive you have to – and then to start despising yourself.

All of this creeps up on you, and by the time you realise what you are looking at it is already too late. It was only after the coup attempt that I saw clearly what had been happening all along – the descent of Turkey’s shaking democracy into one-man rule, the dawn of the state of Erdoğan. While I was focusing on the minutiae of daily news, on the war in Syria and the refugee crisis in Europe, his dominance had grown so entrenched that he had become inseparable from the state, and the state indivisible from the nation. Now, the answer to the eternal question posed by every journalist in Turkey is that it is fine to laugh and question and criticise – so long as you leave Erdoğan out of it. But in a country so monopolised, that leaves very little room for any discussion at all.

I have seen Turkey and Erdoğan through seven elections, dozens of terror attacks, a coup attempt, a civil war, foreign misadventures, slanging matches with Europe, mass street protests, a refugee influx and a massive purge of the public sector. And each time, when I have thought, this must be it, this will finish him , he has come out on top even stronger.

I have to give it to him – Turkey’s president has handed me some great material. Often, I have wished I could hand it back.

Erdoğan is the original postmodern populist. In power for seventeen years, his latest election win in June 2018 means he will stay until at least 2023. Already there is a generation of Turks who can remember little or nothing before the Erdoğan era, and his detractors have much to worry about. They fret over his creeping Islamisation of Turkey, once the staunchest of secular states. They point to his fierce crackdown on Kurdish rebels in the east of his country, where hundreds of thousands have been killed or displaced, and his cosiness with armed rebel groups of questionable ideology in Syria. Europe, which once saw Erdoğan as its darling, now deals with him increasingly as if he were an obnoxious teenager. The inhabitants of the Greek islands within spitting distance of the Turkish coast hold their collective breath and brace each time he threatens to open his borders to allow hundreds of thousands of migrants to flow across the Aegean in cheap plastic boats.

I have spent six years watching Erdoğan, speaking to his followers, and sniffing the winds. I think about him every day and write about him on most days, even though we have never met. But I never set out to be an Erdoğan-watcher, or even to be a Turkey correspondent.

In early 2013 I moved from London to Antakya, a tiny town on Turkey’s southern border with Syria, to pursue a career as a freelance war correspondent. The war next door had turned Antakya into a busy hive of spooks, arms dealers, refugees and journalists. The Syrian rebels had captured two nearby border crossings from President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, and I spent a year crossing back and forth through them into Syria to report on the spiralling slaughter. But as Syria turned darker and colleagues started to go missing at the hands of criminal gangs and Islamist militias, the journalists dropped away from Antakya. Along with most of the Syria reporter crowd I moved north, to Istanbul, where not so much was happening.

The huge Gezi Park protests, which in the spring of 2013 had briefly morphed from small environmentalist demonstrations into the most serious street opposition Erdoğan had ever faced, had now petered out into leftist forums scattered across Istanbul’s upmarket districts. They were happy protests – anyone could stand on a soapbox and, instead of clapping (too bawdy and overwhelming), the audience would wiggle their raised hands in appreciation. I doubt they caused Erdoğan too much anguish. For a year or so after Gezi, small-scale street demonstrations became the city’s number one participation sport – with protagonists boiled down to a hard core who just seemed to enjoy getting tear-gassed. One student ringleader I interviewed talked about upcoming protests as ‘clashes with the cops’, as if that were the main point of the event. The demonstrations became so common and predictable they were more of a nuisance than news. Several times over the course of that year, tear gas seeped into my bedroom as I tried to sleep.

I was bored and sad. I had left Syria, a story I had moved countries for and invested so much energy in. I yearned for the day I could go back and start reporting from there again. I was still dating a Syrian man down in Antakya, and I spent half of my time there with him. Strange as it feels to remember it now, there just wasn’t much of a story up in Istanbul.

But one day I fell in love. Travelling back from Antakya to Istanbul on the cheap late-night flight, I looked out of the window as the plane came in to land in a huge swoop across the city. On either side of the black scar of the Bosphorus, millions of pinprick lights marked out the shape of the shoreline, the traffic-clogged roads, the bridges and the palaces. From above, this scruffy city glistens, and I was glad to be back: it’s a feeling I still get every time the seatbelt sign comes on over Istanbul. It had taken me six months to realise that my banishment from Syria had landed me in the most beautiful, melancholy, fascinating city in the world. Gradually I stopped going down to Antakya, and my relationship with the Syrian fell away.

So, by chance rather than by my own good judgement, I was one of the few reporters based in Turkey full time when the news started flowing – the bombings, the diplomatic spats with Europe, and the overwhelming interest in Erdoğan. As the months progressed, I realised that even the most parochial, insignificant Turkish story could make a headline if Erdoğan were somehow involved. One I particularly remember is a story about his wife, Emine, and a speech she had made suggesting that the Ottoman sultans’ harem, the place where scores of potential sexual partners were kept, could be considered a bastion of feminism. The Western press went nuts – even though there is a serious line of academic debate that would concur with Emine. The interest in Erdoğan, as well as the growing chaos in Turkey, soon landed me regular work filing reports for The Times .

Читать дальше