1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...16 I have no recollection at all.

I remember the roar in my head . . .

I remember the fear in my heart . . .

And then suddenly I was back home again . . . standing at the bathroom sink, my head crashing with electric madness, staring at the nightmare vision in the mirror.

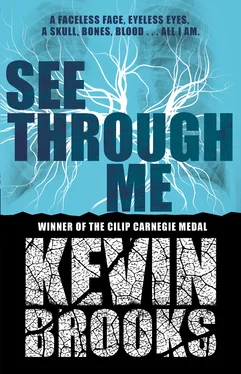

A skull, skinless . . . white bone, grinning teeth . . .

Eyeless . . .

Faceless . . .

Hairless . . .

A skull, pocked with grey stuff and schemes of blood . . .

A thing of death.

It was me.

I could see the tracks of my tears running from the holes where my eyes used to be, the holes looking back at me like caves of bone. I knew my eyes were still there, but it’s hard to believe in something you can’t see.

I closed them.

Something might have flickered in the mirror, just the tiniest shimmer of unseen movement as my invisible eyelids closed . . . but nothing changed. I still couldn’t see the things I was seeing with.

It was too much.

I didn’t want to see anymore.

I covered my eyes with my hands, desperate for the sanctuary of darkness, but all I got was a blurred transparency of finger bones and muscle and blood. The skull in the mirror was still there, still grinning at me through the glaze of my see-through hands . . . and I knew that I didn’t have to keep looking at it, that all I had to do was turn my head and look away, but no matter how much I wanted to – and in that moment I’d never wanted anything more – I just couldn’t do it. I couldn’t do anything. Couldn’t move, couldn’t breathe, couldn’t feel, couldn’t speak . . .

Kenzie?

A voice from a million miles away.

Kenzie!

Your face is who you are. It’s your identity, the thing that makes you you . It’s how you see yourself . . . which is kind of strange, if you think about it, because your face is one of the few parts of your body that you can’t actually see, and the only way you know it is through the second-hand imagery of other things – mirrors, photographs, videos . . .

But it’s still how you see yourself. And it’s how everyone else sees you and knows you too. Your face is you. And because you see it so many times every day – and you’ve been seeing it every day for most of your life – you know it more intimately than anything else. You know every millimetre of it – every line, every turn, every shape . . . the way it all fits together. You know it so well, and it means so much to you, that if it changes in any way at all, you’re instantly and intensely aware of it. And if that change is enough to disturb the familiarity of your face – and it doesn’t take much to do it – the effect can be staggering.

The thing that’s you, and has always been you, has suddenly become something else. It’s not you anymore . . .

That you has gone.

And now you’ve become this . . .

This fucking thing.

I hit it.

My head cracked.

And then I was nothing.

They kept me in the special care room for another two days – the lights permanently dimmed, my body covered up, a sleep mask for sanctuary when I needed it.

‘We’ll move you to a recovery room soon,’ Dr Kamara told me. ‘You’ll be a lot more comfortable there. We just want to make sure there’s nothing else wrong with you first, so we need to keep you hooked up to all the equipment in here for a little while longer.’

I think there was probably a bit more to it than that. I think part of the reason they wanted to keep me under observation in the special care room was so that they could monitor and assess how I was coping – or not – with the shock, and they didn’t want to move me until they were sure I was relatively stable.

I don’t know how I was coping with the shock, to be honest. I remember bits and pieces of the days after the revelation, and some of the memories are all too vivid, but a lot of that time is completely lost to me. I don’t know if I’ve blocked it out, or if I was so traumatised that I never even registered it in the first place. It’s also quite possible that the reason I don’t remember much is that I spent most of the time asleep.

Reasons . . .

Reasons don’t matter.

‘We think it’s best if you don’t have any visitors just yet,’ Dr Kamara said. ‘You need as much peace and quiet as you can get. We’ve talked this over with your dad, and although he’s very keen to see you as soon as possible, he understands that the only thing that matters at the moment is doing what’s best for you. So we’ll give it a couple of days, then hopefully get you into a recovery room and see how it goes from there.’

‘So when will I see Dad?’

‘It’s hard to say. We’d like to keep you fully rested for at least another three or four days –’

‘What about this?’ I muttered, indicating my head, my face. ‘I can’t let Dad see me like this . . .’

‘He’s already seen you, Kenzie. He knows –’

‘When did he see me?’

‘The day after you were brought here.’

‘I don’t remember that.’

‘You wouldn’t. You were in a bad way at the time – you weren’t really aware of anything – and your dad didn’t stay long anyway. He had to get back to look after your brother.’

‘Was I like this when he saw me?’ I asked. ‘Was I . . . you know . . . ?’

‘The transparency hadn’t fully set in at that point. It was still fading in and out, so you weren’t permanently affected when he saw you, but he knows what’s happened to you, Kenzie. He’s seen how you are. He knows –’

‘I’ll have to cover my face when I see him . . . my head . . . all of it . . .’

‘You don’t have to hide anything from him. He’s your dad . . . he’ll understand.’

‘Some kind of veil might do it . . . a niqab maybe, or even a burqa . . .’ I looked at Dr Kamara. ‘Are you allowed to wear stuff like that if you’re not a Muslim?’

She sighed. ‘I wouldn’t know.’

‘Could you find out?’

She just looked at me then, and for a moment I sensed a slight coldness to her.

‘I think you’d better get some rest now,’ she said.

‘But what about –?’

‘I’ve got your clothes here,’ she said, holding up a bulging carrier bag. ‘Burgess Park General just sent them on to us. You need to keep your gown on for now though. You can get changed when you move to the recovery room. Your dad’s going to bring you some more things when he comes – clothes, toiletries, books . . . whatever you need. Is there anything in particular you want him to bring?’

I shook my head.

‘Well, just let us know if you think of anything.’ She leaned down and placed the bag of clothes on the bottom shelf of a monitor stand just to the right of the bed. ‘I’ll leave this here, okay?’

I nodded.

She studied me for a few seconds, and I thought she was going to say something else, but she didn’t. She just turned round, went over to the door, and left.

Reasons . . .

The why of things.

One of the things about dressing the same way nearly all the time is that you can always be pretty sure what you were wearing on any given day. It’s a fairly useless thing to know, and all it really meant that day was that as I lay there staring at the carrier bag, I automatically knew what was in it. The clothes I’d been wearing on that rain-sodden Sunday night would have been the same kind of clothes I always wore – black leggings, black skirt, black T-shirt, black hoodie, my favourite silver and black pumps. I also knew that when I was taken to BPG my phone was in the pocket of my hoodie. Whether it was still there or not was another question, and at first I couldn’t have cared less. What did I want with a phone? I was hardly going to take a selfie and post it on Instagram, was I? And whatever anyone might be saying about me on Snapchat or yapTee or Facebook . . . well, I was feeling bad enough as it was. Why would I want to read a load of stuff that was guaranteed to make me feel even worse?

Читать дальше