But my dad wasn’t a doctor.

He was my dad.

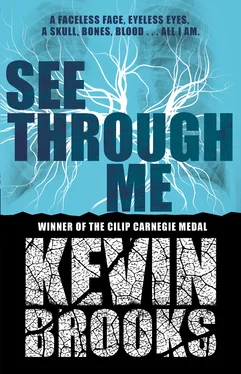

And I knew he wouldn’t be able to hide his repulsion if he saw the horror of my see-through head . . . and I didn’t think I could live with that. I mean, imagine how you’d feel if your dad (or your mum) were so revolted by your appearance that they couldn’t look at you without grimacing in disgust . . .

It would tear you apart, wouldn’t it?

It would turn your world upside down.

‘You can get changed now if you want,’ Dr Kamara told me, putting the carrier bag full of clothes on the settee. ‘You don’t have to,’ she added. ‘You can wait until your dad’s brought some fresh clothes if you want, or if you feel more comfortable keeping the gown on . . . it’s entirely up to you.’

It wasn’t a difficult decision to make. I knew that nothing could make me look normal, but there were still certain things that could make me look a tiny bit less ab normal.

There was nothing normal about the gown.

There was something normal about my clothes.

I turned the lights down low, then went over and sat down on the settee next to the carrier bag. I wasn’t looking forward to getting changed – it meant exposing my body again, and even in the lowest light I was still going to see stuff I didn’t want to see – and for a moment or two I wondered if I could do it with the sleep mask on. It would obviously be quite awkward, but it certainly wasn’t impossible. The only thing was . . .

It didn’t feel right.

I shouldn’t have to be scared of myself.

And even if I was, I didn’t have to be so pathetic about it.

I picked up the carrier bag, placed it on my knees, and reached inside.

The first thing I pulled out was something that shouldn’t have been there. When I’d taken my phone out of my hoodie pocket the other day, the hoodie had been at the top of the bag, and I’d put it back in the same place. But now there was something else on top of it, and I knew it wasn’t mine. It was a smallish polythene bag, and inside it was a pair of sunglasses and a folded-up headscarf. The sunglasses were fashionably large, the kind that celebrities wear, and the lenses were really dark. The headscarf was made from some kind of silky black material.

Dr Kamara . . .

The sunglasses and scarf had to be from Dr Kamara.

Maybe I hadn’t offended after all . . . or maybe I had, but she’d forgiven me. Or maybe it was just me . . .

I don’t get people.

I really don’t.

I opened up the headscarf and held it out in front of me. I didn’t know if it was a hijab or just an ordinary headscarf – I didn’t know the difference, to be honest – but it didn’t matter. It was easily big enough to cover my whole head. And the sunglasses would cover my eyeless eyes.

Twenty minutes later I was standing in front of the bathroom mirror, looking myself over for about the hundredth time. From the neck down, I looked just about normal – pumps, leggings, skirt, T-shirt, hoodie. The only slight oddity was the white gloves on my hands and the white socks on my feet. From the neck up though, I didn’t look normal at all. I’d never even tried on a headscarf before, let alone had to cover my entire head with one, and it wasn’t just a matter of making sure that everything was covered up either. I had to make sure that it stayed covered up, which meant working out how to wrap the scarf round my head in such a way that it wouldn’t come undone.

It took quite a while, but I got there in the end.

And when I put the sunglasses on and pulled up my hood, tightening the drawstring to fix it firmly around my wrapped-up face, every inch of my see-through head was safely hidden from sight.

I looked ridiculous.

But that was okay.

It was the price I had to pay for not looking hideous.

I took out my phone and checked the time. It was 11.46. Not long to go now. As I went back into the room and sat down on the settee, I could feel my heart thumping against my ribs.

Dad was never the same after Mum died. It’s hard to explain how he changed – partly because I can’t really remember how he was before, so I don’t have anything to compare him to, and partly because it was the kind of change that’s very easy to hide. Outwardly he barely changed at all. If you’d asked any of his friends to describe him, they’d have told you that apart from the heartache of losing his wife, he was just the same old Barry Clark.

But he wasn’t.

And Finch and I knew it.

We could never quite work out what it was – whether there was something missing from him, or there was something about him that hadn’t been there before – but we knew, without doubt, that it was all about Mum.

She died very suddenly.

Dad always maintained that she was absolutely fine when she went to bed that night. She wasn’t ill – she’d never had a serious illness in her life – and there was nothing to suggest there was anything wrong with her. She looked well. She hadn’t complained of anything – headache, stomach ache, excessive tiredness – she’d just gone to bed in exactly the same way she always did. Setting the alarm for seven-thirty in the morning, reading a book for half an hour, then turning off the light and going to sleep.

Dad said he couldn’t remember who’d turned off the alarm in the morning. He remembered it going off, but he couldn’t recall if Mum had turned it off or if he’d leaned over her and turned it off himself. He thought he must have gone back to sleep again then, because the next thing he knew it was nearly eight o’clock, and if he didn’t get a move on he was going to be late for work. Mum was lying on her side, facing away from him, and he just assumed she was still asleep. It was a Wednesday, Mum’s day off work (she’d set the alarm so she’d be up in time to see us off to school), so Dad decided to let her sleep in.

We were all a bit late that morning, so when Dad told us that Mum was having a lie-in, we were too busy rushing around to give it any thought. All we were thinking about was getting our stuff ready and grabbing something to eat and – in Dad’s case – guzzling down a cup of coffee and trying to find his car keys.

Dad and Finch left the house first (Dad was dropping him off at school on his way to work), and I left a few minutes later. It wasn’t until I’d got to the bus stop that I realised I hadn’t said goodbye to Mum. None of us had. But I told myself it was okay. She was having a lie-in, wasn’t she? It wouldn’t have been fair to wake her up just to say goodbye.

If only I’d known . . .

If only.

Dad and Finch usually got home before me, but that day Dad was taking Finch to the opticians after school, so I got home first. The house was quiet. I called out to Mum – but only in a casual are-you-there? kind of way – and when she didn’t answer, I didn’t think anything of it. She’d either gone out somewhere or she was upstairs in the bathroom or her bedroom. I didn’t bother calling out again. I was going upstairs anyway – I needed to use the bathroom – so I’d soon find out if she was up there. And if she wasn’t, she wasn’t . . .

It was no big deal.

Nothing to worry about.

The bathroom was at the far end of the landing, and Mum and Dad’s bedroom was halfway along, and as I headed along the landing towards the bathroom I was slightly surprised to see that their bedroom door was shut. They usually only closed it at night . . .

I nearly didn’t do anything.

It was only a closed door . . .

There was probably a perfectly reasonable explanation for it.

I very nearly just walked on past and carried on heading for the bathroom.

But I didn’t.

Читать дальше