| Genus Hydrocoloeus |

|

| Little Gull (H. minutus) |

Regular visitor, very occasional breeder |

| Ross’s Gull (H. roseus) |

Vagrant |

| Genus Xema |

|

| Sabine’s Gull (X. sabini) |

Regular visitor, usually in small numbers |

| Genus Pagophila |

|

| Ivory Gull (P. eburnea) |

Vagrant |

| Genus Chroicocephalus |

|

| Slender-billed Gull (C. genei) |

Rare vagrant |

| Bonaparte’s Gull (C. philadelphia) |

Vagrant |

| Black-headed Gull (C. ridibundus) |

Abundant breeder and winter visitor |

| Genus Larus |

|

| Common Gull (L. canus) |

Common breeder and winter visitor |

| Ring-billed Gull (L. delawarensis) |

Vagrant |

| Great Black-backed Gull (L. marinus) |

Common breeder and winter visitor |

| Glaucous-winged Gull (L. glaucescens) |

Vagrant |

| Glaucous Gull (L. hyperboreus) |

Regular winter visitor |

| Iceland Gull (L. glaucoides) |

Regular winter visitor |

| Kumlien’s Gull (L. glaucoides kumlieni) |

Vagrant subspecies |

| Thayer’s Gull (L. thayeri) |

Vagrant |

| European Herring Gull (L. argentatus) |

Abundant breeder and winter visitor |

| American Herring Gull (L. smithsonianus) |

Vagrant |

| Caspian Gull (L. cachinnans) |

Currently vagrant but increasingly recorded |

| Yellow-legged Gull (L. michahellis) |

Visitor and now an occasional breeder |

| Lesser Black-backed Gull (L. fuscus) |

Abundant breeder |

| Slaty-backed Gull (L. schistisagus) |

Vagrant |

| Genus Ichthyaetus |

|

| Great Black-headed Gull or Pallas’s Gull (I. ichthyaetus) |

Vagrant |

| Mediterranean Gull (I. melanocephalus) |

Rapidly increasing breeder |

| Audouin’s Gull (I. audouinii) |

Vagrant |

| Genus Leucophaeus |

|

| Laughing Gull (L. atricilla) |

Vagrant |

| Franklin’s Gull (L. pipixcan) |

Vagrant |

| Genus Rissa |

|

| Black-legged Kittiwake (R. tridactyla) |

Abundant breeder |

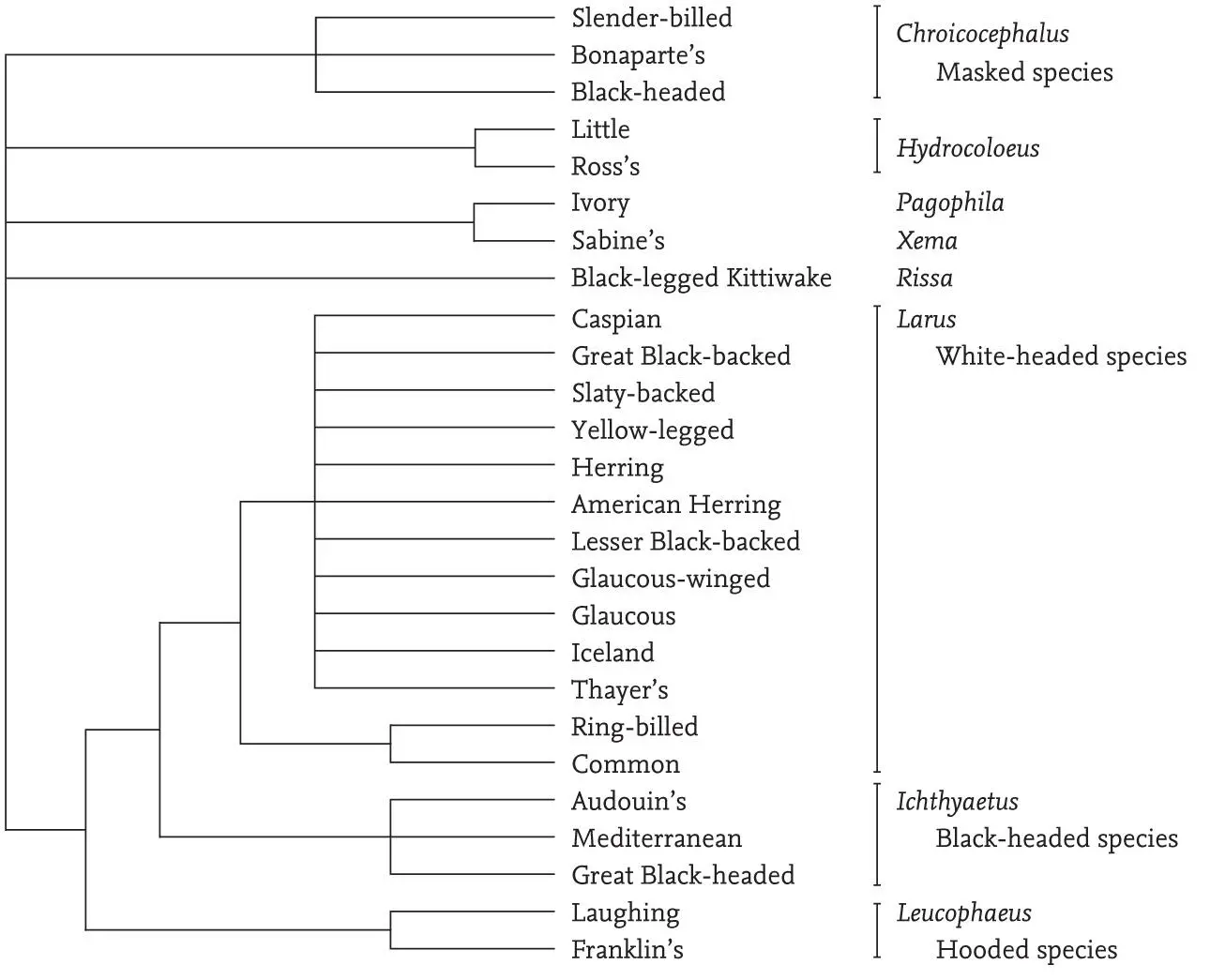

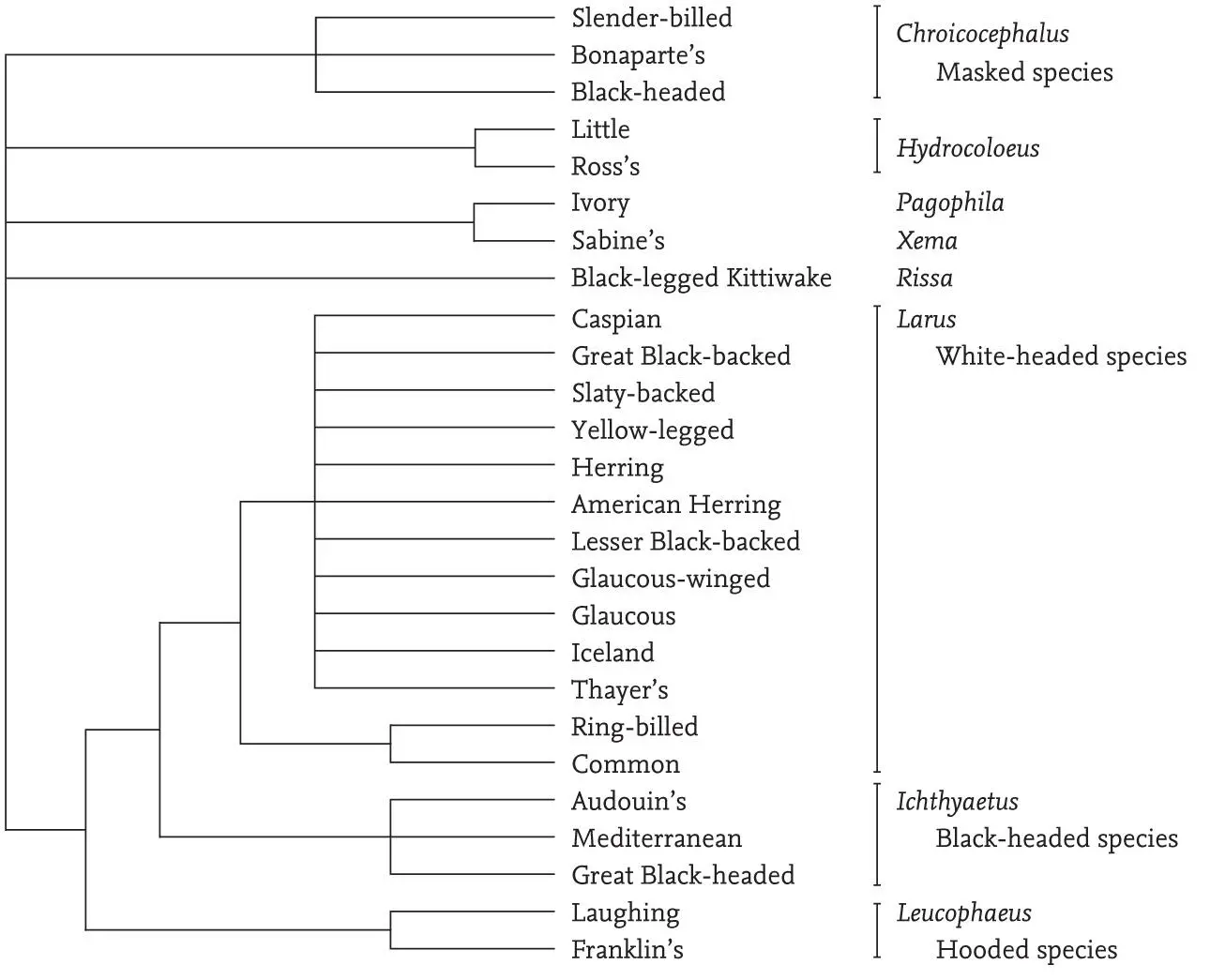

FIG 3. A phylogenetic tree of the gull species that occur in Britain and Ireland. In general, the shorter the line leading from each species, the more recently that species is presumed to have arisen. This does not apply to the large genus Larus, where more work is necessary to elucidate the affinities of the different species. This diagram includes all of the genera in the world, with the exception of the genus Saundersilarus (where Saunders’s Gull, S. saundersi, is the only species) and the genus Creagrus (where the Swallow-tailed Gull, C. furcatus, is the only species), neither of which occur in Europe. The Vega Gull (L. vegae) has not been included, and its presence in Britain has yet to be confirmed, while Kumlein’s Gull is regarded as a subspecies of the Iceland Gull. Based in part on the work of Pons et al. (2005).

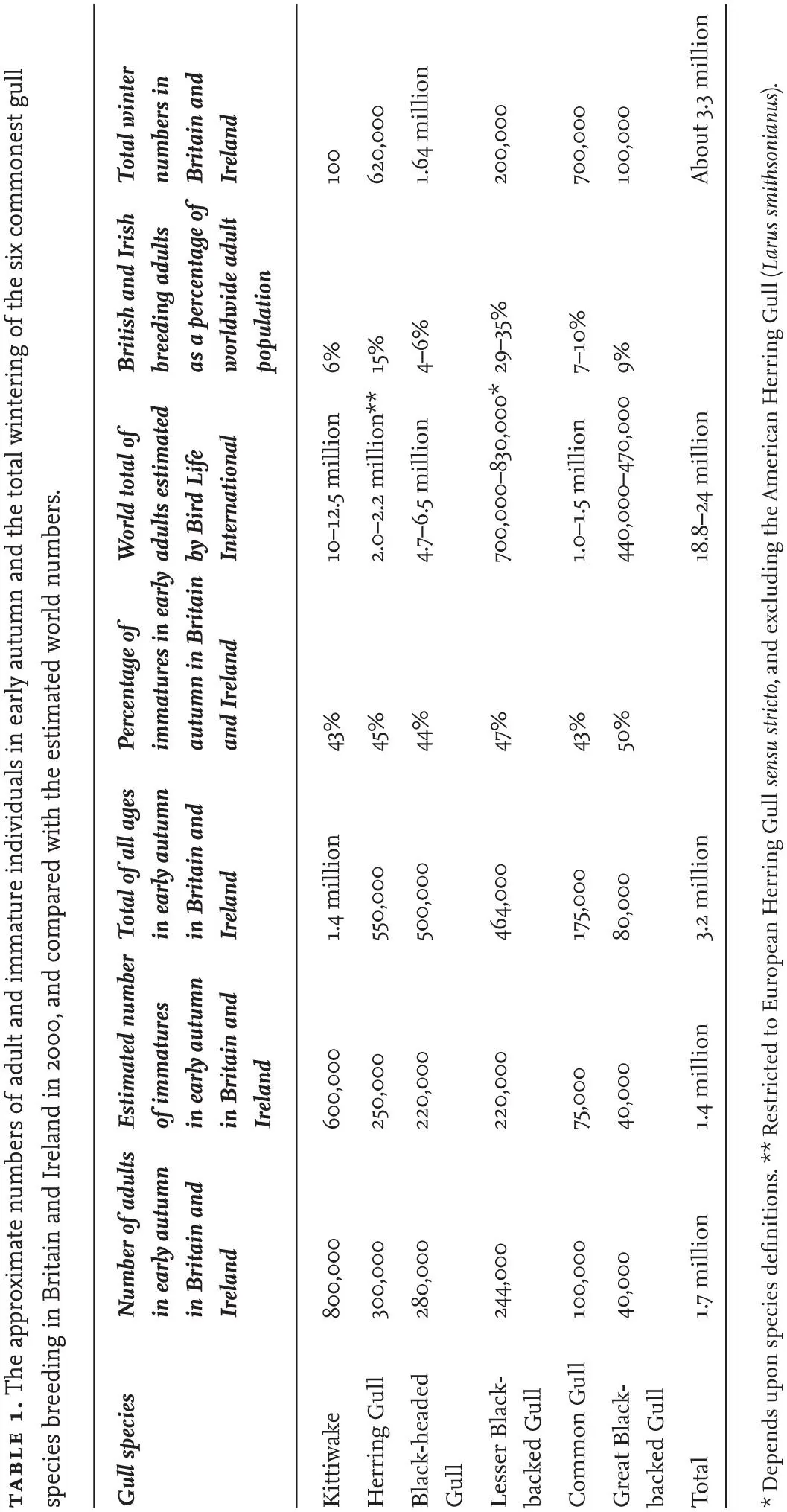

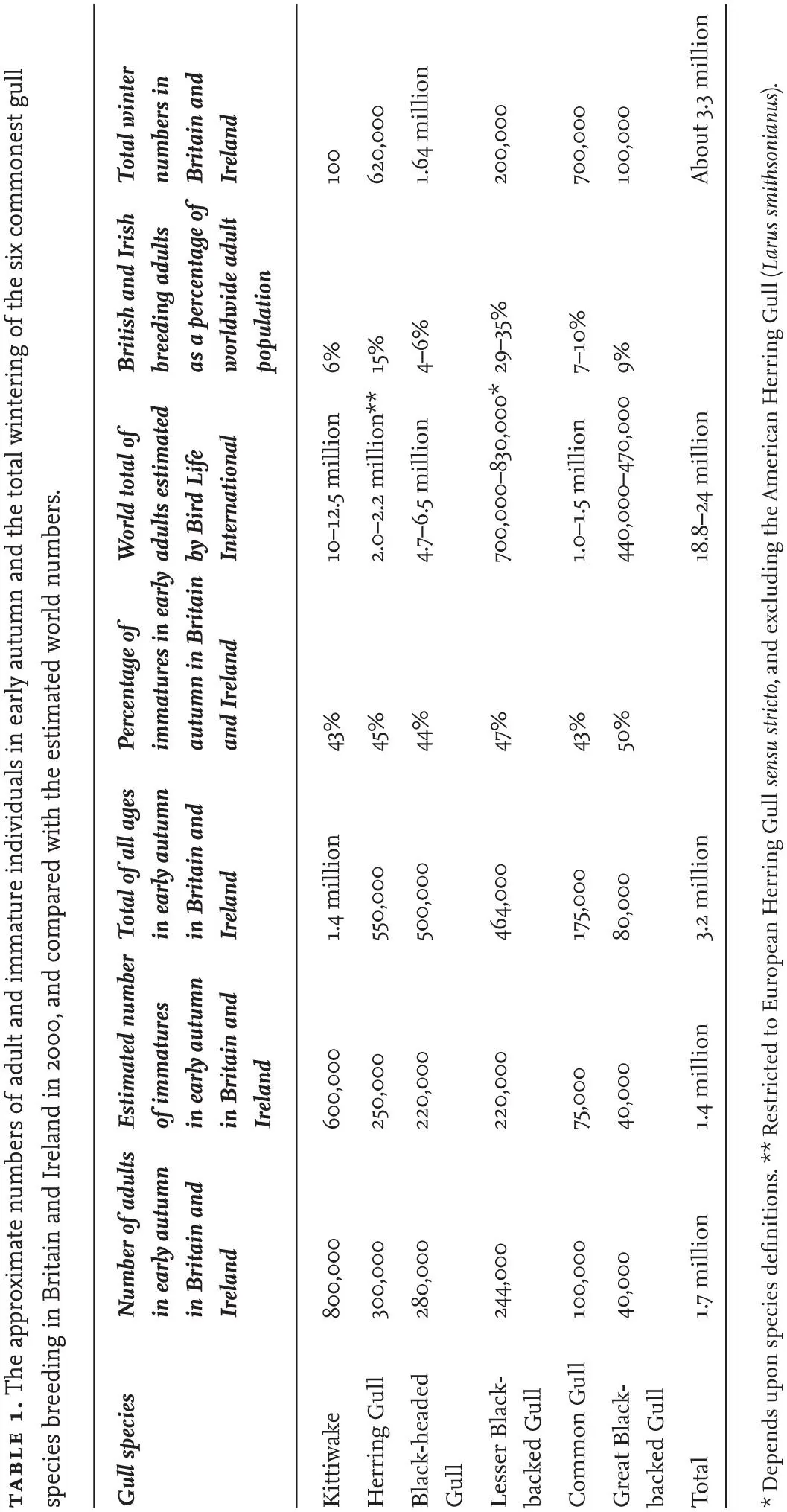

Table 1

also shows estimates of numbers of the six most abundant gulls in Britain and Ireland in about 2000. Again, these figures are estimates, but they indicate that for all six species combined there are about 3.2 million gulls of all ages in Britain and Ireland in the early autumn. This total is probably about 3.3 million in winter, when the numbers of departing Kittiwakes are replaced by immigrant Black-headed, Herring and Common gulls. By late spring, the winter visitors have departed and Kittiwakes have returned to their colonies, maintaining numbers at about 2.6 million just before breeding begins.

SUBSPECIES IN WESTERN EUROPE

There are only a few western European gull species that are represented by more than one subspecies. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, the Herring Gull was previously split into several named subspecies, some of which have now been elevated to species (Yellow-legged Gull, Caspian Gull). Two subspecies occur in Britain and Ireland: Larus argentatus argenteus, which breeds here; and the larger, darker L. a. argentatus, which breeds in northern Scandinavia and north-west Russia, and winters in Britain and the North Sea region. The nominate Common Gull subspecies, L. canus canus, occurs widely in western Europe, while the larger, darker subspecies L. c. heinei, which breeds in Russia, probably (based on ringing data) occurs occasionally in Britain, but is difficult to identify. In the Atlantic, the Kittiwake is represented by a single subspecies (Rissa tridactyla tridactyla); individuals are progressively larger towards the north of its range, but this gradual change does not justify separate subspecies status and is described as a cline. There are probably several other clines among gulls that are yet to be recognised, including the Black-headed Gull, Glaucous Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull.

SURVIVAL AND LONGEVITY

Gulls are medium- to long-lived birds, with an average expectation of adult life and number of breeding years of different species ranging between four and 12 or more years. Annual adult survival rates for different species vary between 80 per cent and 92 per cent, and often vary appreciably from year to year and over longer periods of time. The annual survival rate tends to be higher in the larger gulls, which also have a longer period of immaturity. This delay in reaching breeding age in gulls appears to be associated with the time that is necessary to acquire competence in obtaining food, but why this should be longer in the large species is not evident. Ringed Herring Gulls that are nearly 35 years old have been recorded, but these represent a few extreme individuals comprising less than 1 per cent of those that reached maturity. In several gull species, the peak of mortality occurs during and just after the breeding season, when the adults are at their lowest weights during the year, suggesting that breeding is a significant stress. Data suggest that survival of gulls is usually high in winter, but the Kittiwake may be an exception, with most mortality occurring while the species is in its pelagic wintering range.

Less is known of the survival of immature gulls, but there is usually a lower survival rate in the 12 months following fledging, after which the survival rate approaches that of the adults.

The longevity records based on birds ringed as nestlings and living under natural conditions are given below, although several individuals are known to have lived longer in captivity.

| Mediterranean Gull |

22 years 1 month |

| Little Gull |

20 years 11 months |

| Black-headed Gull |

30 years 7 months |

| Common Gull |

33 years 8 months |

| Lesser Black-backed Gull |

34 years 10 months |

| European Herring Gull |

34 years 9 months |

| Great Black-backed Gull |

29 years 2 months |

| Black-legged Kittiwake |

28 years 6 months |

| Ivory Gull |

23 years 11 months |

| Laughing Gull |

22 years 1 month |

| Ring-billed Gull |

27 years 6 months |

| Glaucous-winged Gull |

23 years 10 months |

The species with the longest recorded lifespans are mainly those that have been ringed in large numbers, and therefore have more chance of an exceptional record. It should be kept in mind that these lifespans are reached by exceptional individuals – perhaps one in several thousand – and so it is very likely that the maximum known age of many gull species in the wild will increase in future years as more recoveries of marked birds accumulate.

Читать дальше