þe túlk þat þe trámmes . of trésoun þer wróʒt

Watz tríed for his trícherie . þe tréwest on érthe

Hit watz Énnias þe áthel . and his híghe kýnde (9/3–5)

In the practice of these poets, any vowel may alliterate with any other vowel and with h‐ , as in the last line quoted.

This structural alliteration normally falls on stressed syllables. As already described in 2.4, the way a word is stressed in Modern English is generally a good guide to its Middle English stress‐pattern, although there are some variations, particularly in French loan‐words. So ‘deserved’ alliterates and is stressed on the first syllable in

Such a dúnt as þou hatz dált . dísserved þou hábbez (9/452)

‘Important’ words (nouns, adjectives, adverbs and verbs) are normally stressed in preference to ‘little’ words (prepositions, articles and conjunctions). When an adjective accompanies a noun, either may be stressed, as the following line illustrates:

Of brýʒt golde upon silk bórdes . bárred ful rýche (9/159)

Sometimes there are three alliterating syllables in the first half‐line. It may be appropriate to subordinate one of these, so that in the following the first word, siþen , is presumably unstressed, though alliterating:

Siþen þe sege and þe assaut . watz sesed at Troye (9/1)

Yet it is more difficult to subordinate the noun borʒ in the next line:

þe borʒ brittened and brent . to brondez and askez (9/2)

Non‐standard alliterative patterns, such as ax/ax or aa/xx , are also found, but many of them are perhaps the result of scribal error. An obvious example of such corruption is:

Wolde ʒe worþilych lorde . quoþ Gawan to þe kyng (9/343)

where we have adopted the simple emendation to Wawan , a form of Gawain’s name used elsewhere by the poet, to restore the standard alliterative pattern.

A stressed syllable is called a lift , a group of unstressed syllables a dip . The dips vary in length, and this determines the rhythmic structure of the half‐line. In the following two lines, the first has a four‐syllable dip before the first stress, while the next has no dip at all between the stresses of the second half:

þat siþen depréced próvinces . and pátrounes bicóme

Wélneʒe of al þe wéle. in þe wést íles (9/6–7)

A dip of one syllable may be called ‘weak’, and ‘strong’ if it is more than one syllable. In the second half‐line (the ‘b‐verse’) the rhythm is quite tightly controlled, with a maximum of eight syllables and a minimum of four. Furthermore, one of the dips preceding the two lifts must be strong, the other must not be strong. So in the b‐verse of l. 6 above, the first dip (‘and’) is weak, the second is strong; in l. 7 the first stress (‘west’) is preceded by a strong dip, and followed immediately without a dip by the final stressed syllable. If there is a dip at the end of the line it is always weak. For a fuller account, see H. N. Duggan in Derek Brewer and Jonathan Gibson, eds, A Companion to the Gawain‐Poet (Cambridge, 1997), pp. 221–42.

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight , from which all these examples have been taken, a varying number of alliterative lines is rounded off by a rhyming ‘bob and wheel’ of five lines, the ‘bob’ of one stress and the four lines of the ‘wheel’ of three stresses.

The basic description of the alliterative line applies also to the verse of Piers Plowman , but the variations in Langland’s line are considerably greater than those in the Gawain ‐poet and the other writers of the North‐West. One very characteristic feature of Langland’s verse is the alliteration of an unstressed syllable before a non‐alliterating stressed syllable. So in this second half‐line, fro alliterates but morw‐ is stressed:

And flápton on with fláles . fro mórwen til éven (7b/180)

Variant alliterative patterns, in particular aaa/xx and aa/xa , are found quite frequently in Piers Plowman and are perhaps authentic, but scribal intervention in this text is a major problem, and many of the metrical anomalies may be a result of corruption.

Laʒamon, writing in about 1200, used both rhyme and alliteration, sometimes as alternatives, sometimes together. He seems to have relied on two distinct models: the stress‐based alliterative line of Germanic tradition, and the rhyming couplets of Romance verse. The alliterative line was inherited from Old English, but perhaps not directly; there are examples even from before the Conquest of a much looser alliterative line with sporadic internal rhyme. On this model Laʒamon superimposed a metre learnt from Anglo‐Norman and Latin poets writing rhyming verse. In Laʒamon’s Brut the half‐lines are of varying length, predominantly of two stresses, and are linked to one another sometimes by rhyme or half‐rhyme, sometimes by alliteration, sometimes by both. With rhyme but not alliteration is:

Híʒenliche swíðe . fórð he gon líðe (3/4)

The next line has alliteration but not rhyme:

þat he bíhalves Báðe . béh to ane vélde (3/5)

Two lines further on, the word burnen both alliterates and rhymes with the second half‐line:

And ón mid heore búrnen . béornes stúrne (3/7)

In his work Laʒamon was recreating a heroic British past for an Anglo‐Norman present, and his metrical form, like other features of his style, recalls pre‐Conquest traditions. Yet his Brut does not attempt to reproduce an Anglo‐Saxon verse form, but instead develops English verse by assimilating Continental traditions.

7 From Manuscript to Printed Text

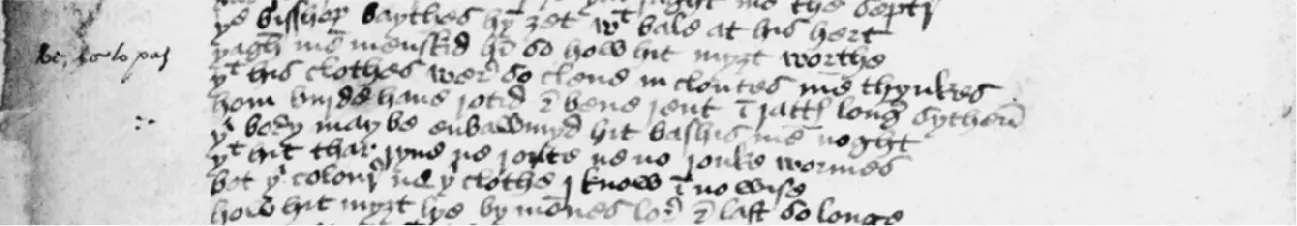

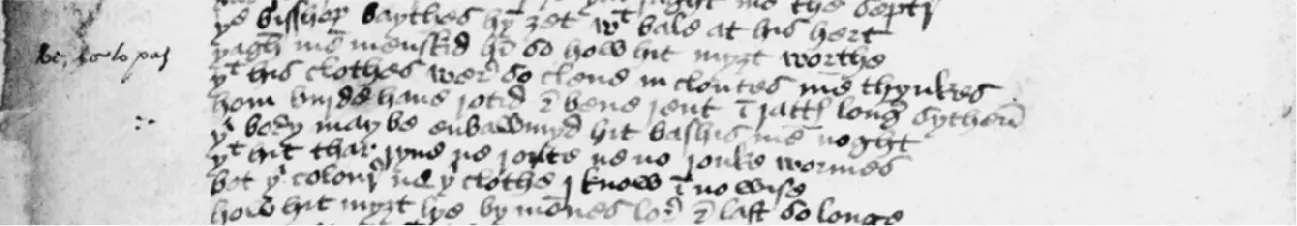

The following is a passage from one of our texts (11), St Erkenwald lines 257–64: first, as it appears in the one surviving manuscript copy; then, as it would appear in a ‘diplomatic’ or letter‐by‐letter transcription; and finally, as it appears in our edited version.

Lines from St Erkenwald (MS Harley 2250, folio 74v).

Reproduced by permission of the British Library.

|

y ebisshop baythes h  ʒet w tbale at his hert ʒet w tbale at his hert |

be, c  to paf to paf |

yagh mē menskid h  so how hit myʒt worthe so how hit myʒt worthe |

|

y this clothes we  so clene in cloutes me thynkes so clene in cloutes me thynkes |

|

hom burde haue rotid & bene rent  ra ra  lon lon  sythe sythe  |

| ∵ |

y ibody may be enbawmyd hit bashis me noght |

|

y thit thar ryne ne ro  te ne no ronke wormes te ne no ronke wormes |

|

bot y icolou  ne y iclothe I know ne y iclothe I know  no wise no wise |

|

how hit myʒt lye by mōnes lo  & last so longe & last so longe |

þe bisshop baythes hym ʒet with bale at his hert,

Читать дальше

ʒet w tbale at his hert

ʒet w tbale at his hert to paf

to paf so how hit myʒt worthe

so how hit myʒt worthe so clene in cloutes me thynkes

so clene in cloutes me thynkes lon

lon  sythe

sythe

te ne no ronke wormes

te ne no ronke wormes ne y iclothe I know

ne y iclothe I know