Hannie van Genderen - Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Hannie van Genderen - Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Shema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder

Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder

Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

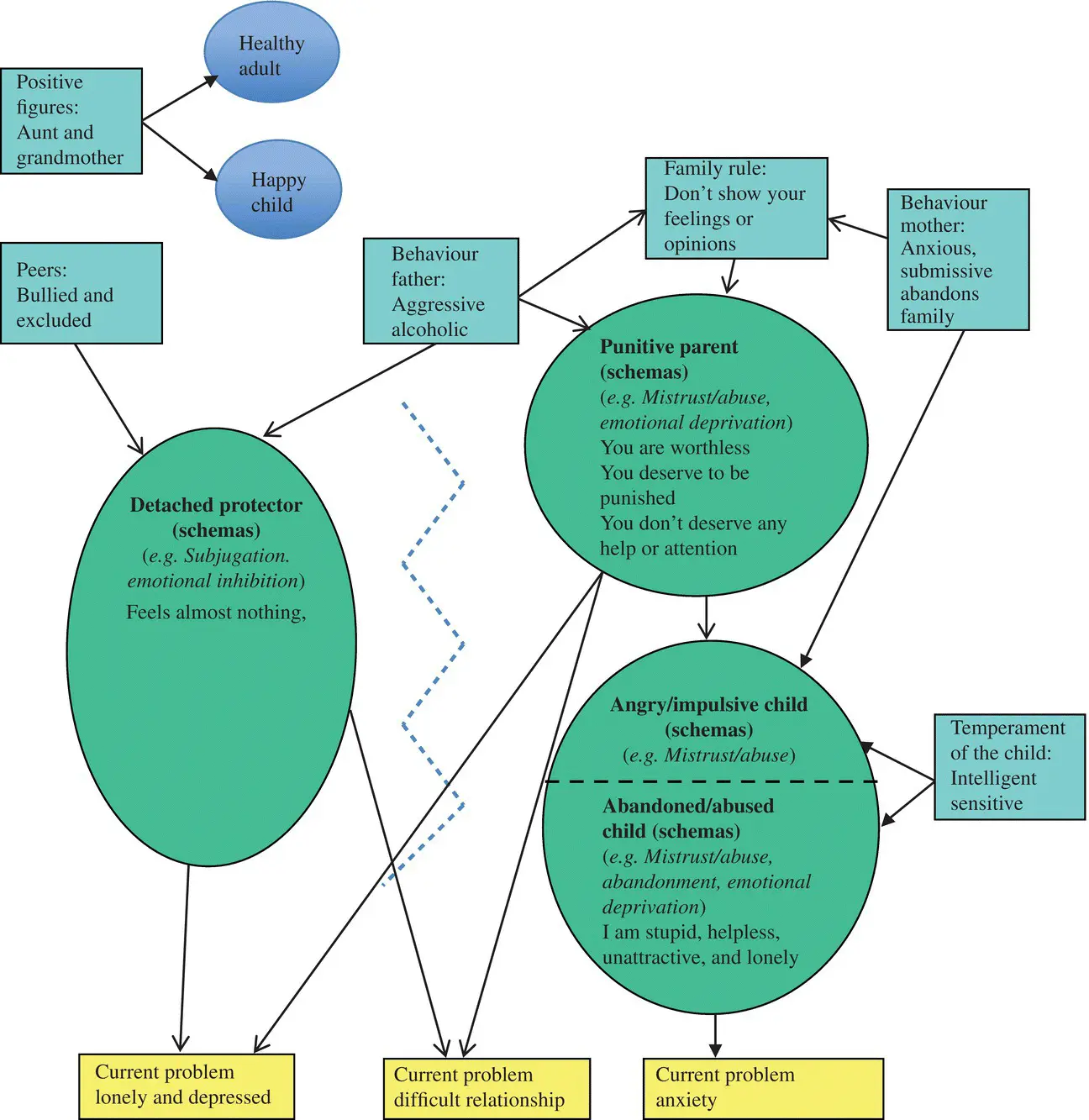

The patient also doesn't look happy or relaxed (happy child). Underlying assumptions that play important roles here are those of: it is dangerous to show your feelings and/or desires and to express your opinion. The patient fears losing control of her feelings. She attempts to protect herself from the alleged abuse or abandonment. This becomes particularly evident as she becomes attached to others. The protector keeps other people at a distance either by not engaging in contact or by pushing them away (the detached protector can become an angry protector (see ST step by step 5.11) or a bully and attack mode (see ST step by step 5.13 and 5.14)) or belittle them by denigrating them (self‐aggrandizer see ST step by step 5.12)). Should others discover her weaknesses, the patient would face potential rejection, punishment, and/or abandonment. Moreover, if the patient would allow to fully feel emotions and emotional needs, the dysfunctional modes to the right of the “wall” in Figure 2.2might get activated, which is a frightening prospect for the patient, as she does not know well how to deal with that. Therefore, it is better to not feel anything at all and keep others from getting too close to her, and to prevent emotions to be felt.

Figure 2.3 Borderline personality disorder: an example of a case conceptualization linking modes with the origins in youth, schemas, and current problems

The therapist should try to find a special name for the detached protector of Nora. A lot of patients call their protector a wall or a shield. This helps to make clear what the function of this mode is.

Sample dialogue with a patient in the protector mode

(In this example and following dialogues, “T” is therapist and “P” is patient.)

T:

How are you doing?

P:

(with no emotion) Good.

T:

How was your week, did anything happen that you would like to talk about?

P:

(looks away and yawns) No, not really.

T:

So, everything's OK?

P:

Yeah, everything's OK. Maybe we could have a short session today?

Should simple methods of avoiding painful emotions prove ineffective, she may attempt other manners of escape, such as substance abuse (such actively soothing emotional pain is called a self‐soother mode), self‐injury (physical pain can sometimes numb psychological pain), staying in bed, dissociation or attempting to end her life. BPD patients often describe this mode as an empty space or a cold feeling. They report feeling distanced from all experiences while in this mode, including therapy.

If the patient is not successful at keeping people at a distance, she can become angry and cynical in an attempt to keep people away from her. It is important for the therapist to recognize these behaviors as forms of protection and not be put off by them. If this angry–cynical state is very pronounced, it can be distinguished as a separate “angry protector” mode. The patient could even attack the therapist (the bully and attack mode) or she can disagree with the therapist in a condescending way (the self‐aggrandizer).

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish the angry protector or bully and attack mode from the punitive parent, especially during the initial stages of the therapy. One manner of distinction is to observe the direction of the patient's anger. While the angry protector's anger is directed toward the therapist (or someone else), the punitive parent's anger is directed toward the patient herself. If the therapist is unsure of the mode he is presented with, he can simply ask the patient if she is able to disclose which “side” of her personality is currently active.

Sample dialogue with patient in the angry protector, the bully and attack mode, the self‐aggrandizer, and the punitive parent mode (See ST step by step 5.11, 5.12, 5.13, 5.14, and 5.20)

T:

When I told you that I have the next week off, your reaction was pretty angry. What mode do you think that reaction came from?

Response from angry protector:

P:

Oh No! We're going to have another lecture about that stupid borderline model of yours? You couldn't wait, could you? Can't think of anything, better can you?

T:

I think your angry protector mode is activated because you feel to be left alone the next week.

P:

Do you really think you're that important for me? I do not need anybody.

Response from a bully and attack mode:

P:

I see that you do not really know what you're talking about. You only pretend to be a good schema therapist.

T:

(he has a tendency to defend himself) I really think I know which side of you is this.

P:

O you are such a loser if you talk like that.

T:

I do not like it when you talk to me like that.

P:

(laughing) Now you are insulted huh? That is not very professional behavior.

Response from a self‐aggrandizer:

P:

I am not angry at all. I am only irritated because you have planned your holiday at the wrong time. Exactly before my holidays. Can't you postpone your holiday?

T:

No, I'm not going to do that. Which side of you thinks I should adapt to you?

P:

Should I explain ST to you? I thought that limited reparenting was the core of your therapy. If you really think that I am important you would postpone your holiday.

Response from punitive parent:

P:

I don't know which “side” of me this is. I only know that I must have been a complete idiot to trust you and that is one mistake I won't make again. It doesn't matter anyway; I'll never get better and I don't deserve to get better.

T:

I think I hear the voice of your punitive parent mode. Maybe that side says that you make a fool of yourself by having sad or angry feelings.

P:

That's not my punitive parent mode, but a fact. It is childish behavior when you only have 1 week holiday.

In the beginning of the therapy, the subtle differences between the angry protector or bully and attack mode and the angry child can also be difficult to distinguish. The differences are primarily evident in the level of anger that is paired with the reaction (see the section “angry/impulsive child”), and in the intention underlying the anger. Whereas, with the angry protector, the intention is to keep others away to protect oneself for being abused, rejected, or abandoned, with the angry child the intention is to protest against maltreatment by others and to get recognition for one's (interpersonal) needs.

These examples involve the protector expressing herself in an active manner. The completely opposite form in which the protector may express herself is by exhibiting tired or sleepy behavior. In this case the therapist must assess whether or not the patient is actually tired or whether she is in the protector mode.

There is the risk that while in the protector mode, the patient may avoid therapy and not work on her problems with a serious chance of her stopping therapy all together. The patient can also have problems with dissociative symptoms, self‐injury, addiction to numbing substances (e.g., drugs or alcohol), or may attempt suicide. Because of this, it is important to identify when the protector mode is present and bypass it. This will give the patient an opportunity to work on her actual problems.

How to recognize a detached protector mode during a session

The patient is not making real contact with the therapist

The patient doesn't show emotions, even if she talks about emotional experiences

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.