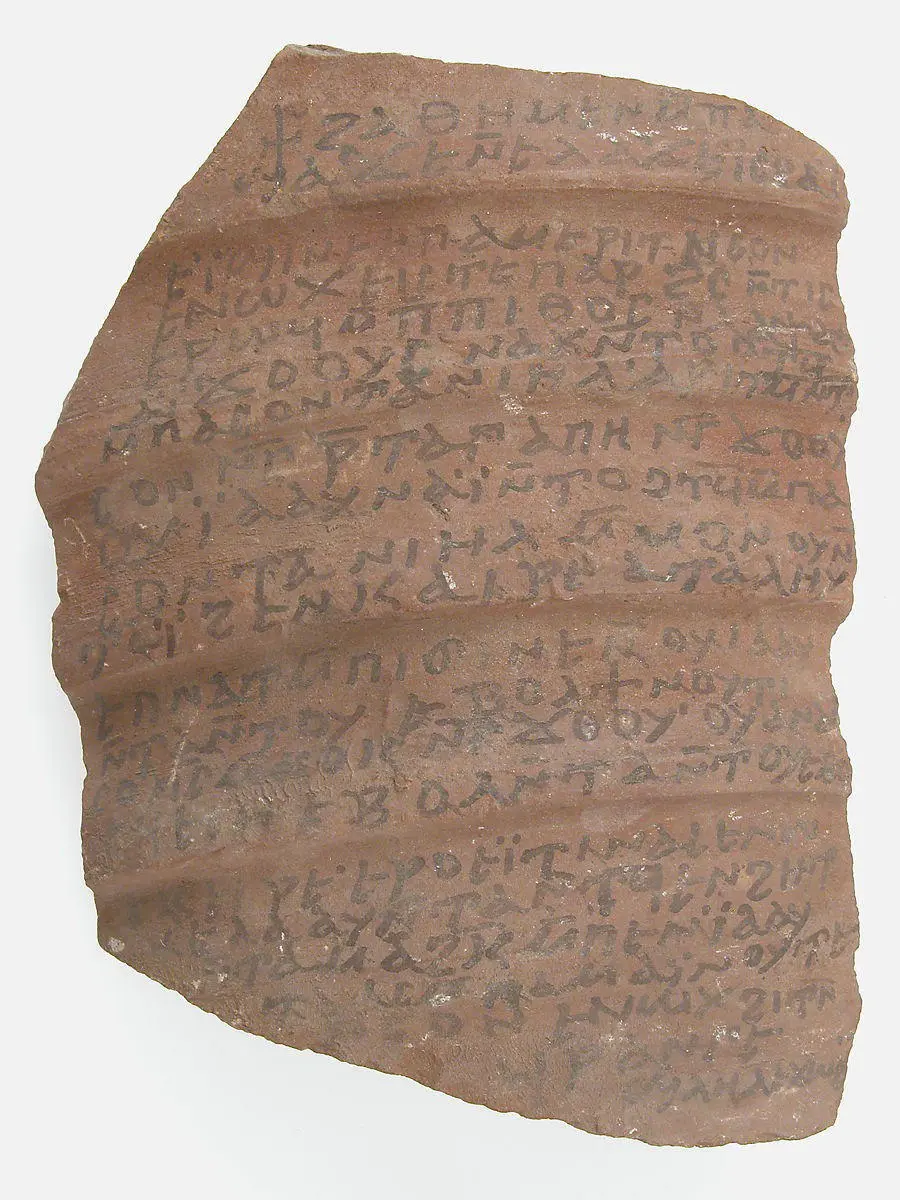

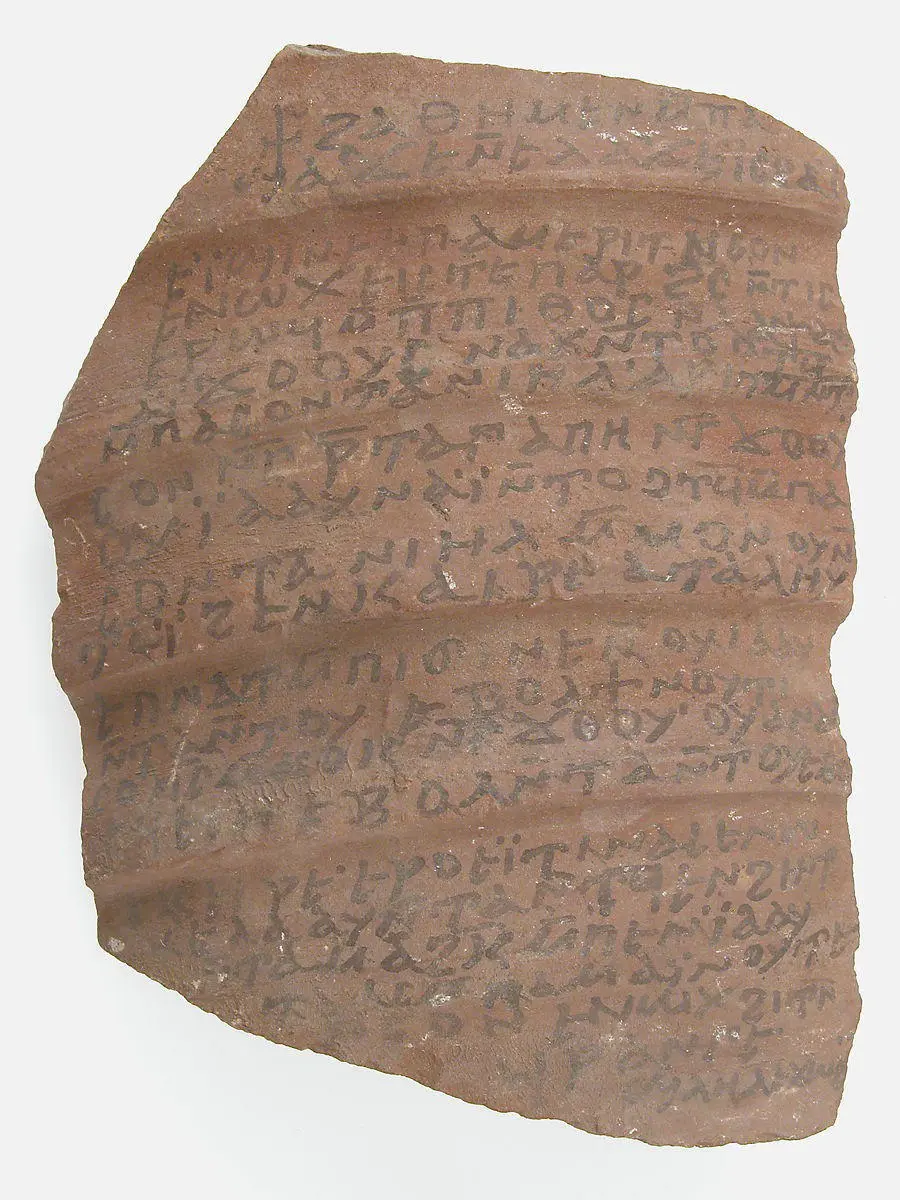

Greek script also influenced the writing of Egyptian. The Coptic script, first attested in the 2nd century AD, was an alphabet that included vowels and was derived from the Greek, with seven signs borrowed from Demotic to indicate sounds not present in Greek. The earliest Coptic writings were magical spells whose correct pronunciation was important and which required an explicit indication of the vowels. Soon Coptic became the script of the Egyptian Christian church for religious purposes as well as for documents of daily practice. It continues to be used today and the knowledge of it was important for the decipherment of hieroglyphs in the 19th century AD ( Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 In the first few centuries ad Coptic script was developed to write the last stage of the ancient Egyptian language, also called Coptic. The script was based on the Greek alphabet, with a number of letters added to it to render new sounds, and survives until today. Around 600 ad a weaver wrote the pottery ostracon (15 by 11 cm) shown here to request linen from a monastery. It was excavated in the Monastery of Epiphanius at Thebes. Metropolitan Museum of Art 14.1.157.

Source: Rogers Fund 1914

Because many texts were handwritten, all the forms of the script had their variants, which we call cursive and abnormal. The differences were temporal, regional, and also depended on who wrote. Reading Egyptian always involves a degree of decipherment and requires a good knowledge of the language, which itself constantly changed. Because all scripts except for Coptic rendered vowels only in special circumstances and no one speaks ancient Egyptian any longer, we are uncertain about how to vocalize words. Thus some speak of the god Re, others of Ra. Many Egyptological publications quote terms and titles by their consonants alone, which is disorienting to the beginner but reflects Egyptian practice.

In ancient Egypt writing always remained a restricted skill and the preserve of the privileged, most often men and some women attached to the court. We cannot estimate the literacy rate at any time, but it was certainly very low in the beginning and only gradually grew with the expansion of bureaucracies in the Old Kingdom. The esoteric character of writing gave those who knew it a special power. While many Egyptians may have seen inscriptions, only a few could understand them.

Key Debate 2.1 The impetus to state formation in Egypt

Egypt stands out among early states in world history. In most other cases – but not all (Trigger 2003 : 104–113) – political entities incorporating limited territories, usually a city and its surroundings, for long periods of time preceded the existence of the territorial state. In contrast, almost as soon as the state arose in Egypt there was a unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, a vast territory. Why did the evolution there lead almost immediately to a territorial state?

Over the years scholars have formulated many explanations under the influence of various ideological and intellectual trends (cf. Hendrickx 2014 ). Early investigators, inspired by European ideals of historic progress through imperialism, thought that an outside force was responsible. A “dynastic race” arrived from the north and unified Egypt by conquest – archaeologists thought they could even identify their skeletons in Early Dynastic cemeteries (as discussed by Bard 1994 : 1–5). The Egyptian visual evidence suggested otherwise, however. The Narmer Palette and similar objects showed that Egyptians defeated other Egyptians. For a long time historians thought that at first two separate kingdoms (Upper and Lower Egypt) existed, becoming one at the start of Egypt’s historical period. They disagreed on what kingdom was victorious and what king accomplished the unification. Inspired by later mythology, some thought that the Delta subdued the Nile Valley (Sethe 1930 : 70–78); more believed that the south conquered the north. Much discussion revolved around who was the first to unite the two countries. Narmer seemed a likely candidate, but the somewhat earlier King Scorpion appeared with both Upper and Lower Egyptian symbols as well (I. Edwards 1971 : 1–15). The idea that there existed two equivalent states was deemed unlikely, however, especially since the Delta showed no central political organization before the overall unification of Egypt (Frankfort 1948 : 15–23). Thus the theory that a regional elite expanded its power gradually over the entirety of the country by eliminating competitors gained hold. The process started long before the ultimate unification of the country (Helck 1981 : 24–44).

This still did not explain why territorial unification occurred. Theories that the concept was inspired from abroad – Babylonia and Nubia have both been suggested – are mostly rejected now (cf. Midant‐Reynes 2003 : 275–307), and scholars prefer to focus on indigenous forces. Many think that centers of production and exchange developed along the Nile Valley and that elites in them sought increased territorial powers to gain access to trade items and agricultural areas. When the zones of influence of neighboring centers started to intersect, conflict arose, which was settled through either war or alliances (Bard 1994 : 116–118). But Egypt was rich in resources and had a small population in late prehistoric times, so why would people have competed over them? The desire to control access to foreign goods is thus often seen as the trigger for state formation (Morris 2018 : 11–38). Non‐materialist motives also may have driven expansion. People who settled down became territorial and, like players in a Monopoly game, tried to expand their holdings. Thousands of such games took place along the Nile, and increasingly fewer players became more powerful until one triumphed (Kemp 2018 : 70–75). Conquest was not necessarily the main force of unification; peaceful arrangements (marriages, etc.) may have been more important (Midant‐Reynes 2003 : 377–380).

In recent years, the view that the valley was the primary locus of change has been under attack as the result of much more research in the desert, which was more fertile in the 4th millennium BC than it is now. Archaeologists have shown that there was extensive pastoral life there and that inhabitants of the valley wanted to control access to desert routes. Part of the evidence derives from rock art in the eastern desert (T. Wilkinson 2003 : 162–195); other evidence comes from the western desert oases (Riemer 2008 ). For centuries the pastoralists who moved around outside the valley were more active and wealthier than those who farmed. They developed a greater social hierarchy and an elite that controlled resources, and brought these concepts to the valley when forced to move there in the mid‐4th millennium because of a dryer climate. Ultimately, at the end of the millennium, it was such elites who unified the whole of Egypt – valley, Delta, and desert regions – into a vast territory with a bureaucracy to administer it (Wengrow 2006 ). The question still remains, however: why?

Egypt’s location on the junction of Africa and Asia made it natural that it was in contact with cultures on both continents, and the development of the Egyptian state had a great effect on neighboring regions. There are also indications that outside cultures may have triggered events in Egypt, but historians differ much in opinion on this question.

The Uruk culture of Babylonia

The 4th millennium was also a period of crucial change in Babylonia – the region of southern Iraq and western Iran – that culminated in the appearance of the state. In contrast to Egypt, the focus of the state in Babylonia was the city, and several city‐states existed side by side. But many characteristics of the ancient Egyptian state appeared in Babylonia as well, such as social stratification, monumental architecture, bureaucracies, and writing. The development in Babylonia seems to have been more gradual than in Egypt, and may have concluded slightly earlier, around 3200 rather than 3000. But the absolute dating of the archaeological data that underlies our reconstructions has such a margin of error that it is not a reliable means to determine precedence.

Читать дальше