In the Nile Valley, the extensive use of agriculture with permanent settlements nearby only arose after 4000 BC. It was the result of the Upper Egyptian pastoralists moving close to the river because of the drying of the climate. This development only occurred north of the 1st cataract, distinguishing Egypt from Nubia, where the economy remained focused on pastoralism. In Egypt, urban centers appeared and people went to live near the zones that the Nile flooded annually to work in the fields. Until the building of the Aswan dams, agricultural practices in Egypt were very different from those in the neighboring Near East and Europe. The country received too little rain to rely on its water to feed the crops, and the Nile was the farmer’s lifeline. That river’s cycle provided everything needed, however, and the Egyptians relied on natural irrigation. The water rose in the summer, washing away salts that impede plant growth and leaving a very fertile layer of silt on the fields bordering it. The water receded in time for the crops – all grown in winter – to be sown and it left the fields so moist that they did not require additional water while the plants grew. Farmers harvested crops in the late spring and the fields were ready for a new inundation by July. The cycles of the river and the crops were in perfect harmony. The only concern was the height of the flood, which dictated how much land received water. The ideal flood was somewhat more than 8 meters above the lowest river level. If the river rose too much, villages and farms would be submerged; if it rose too little, not enough land would be irrigated.

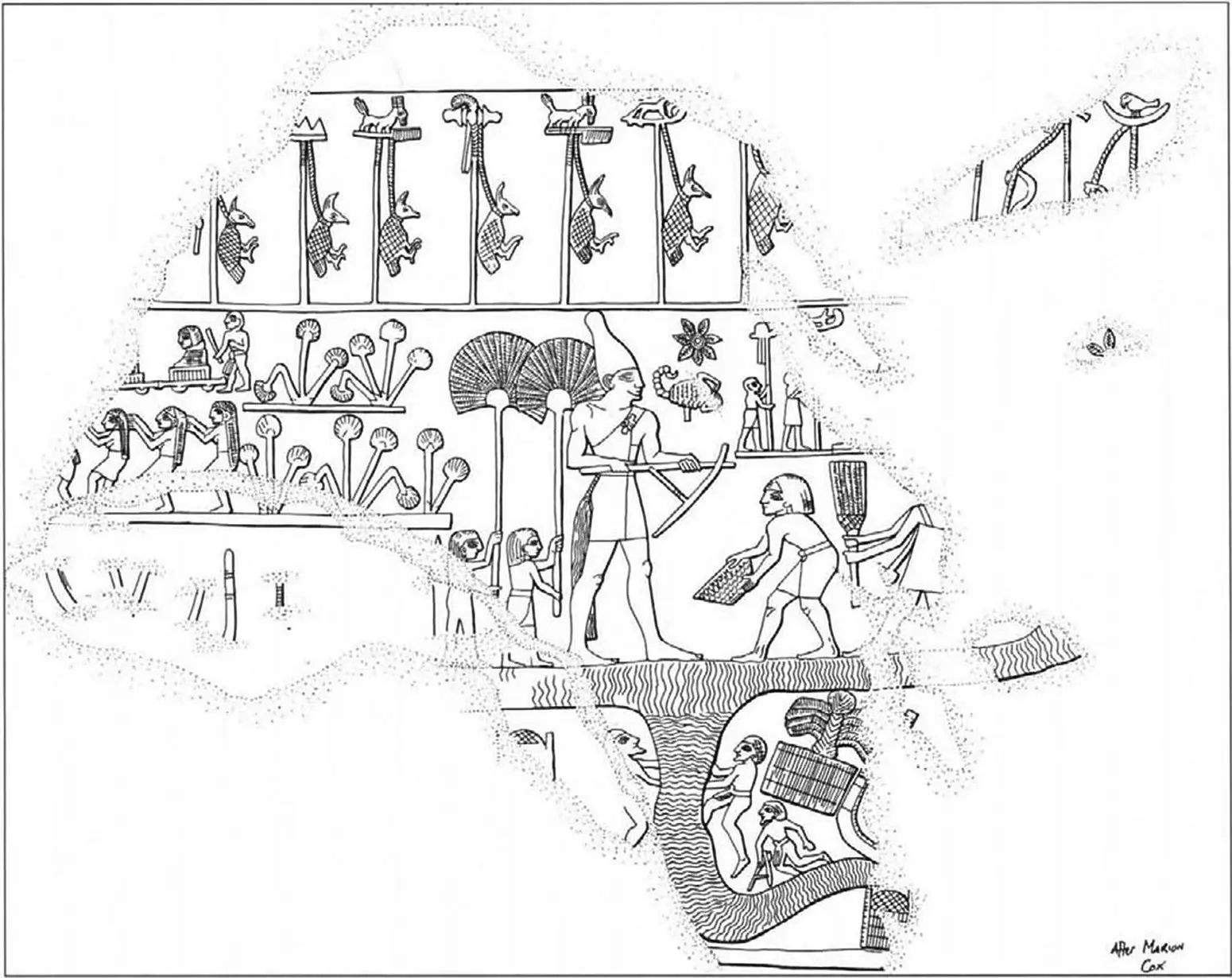

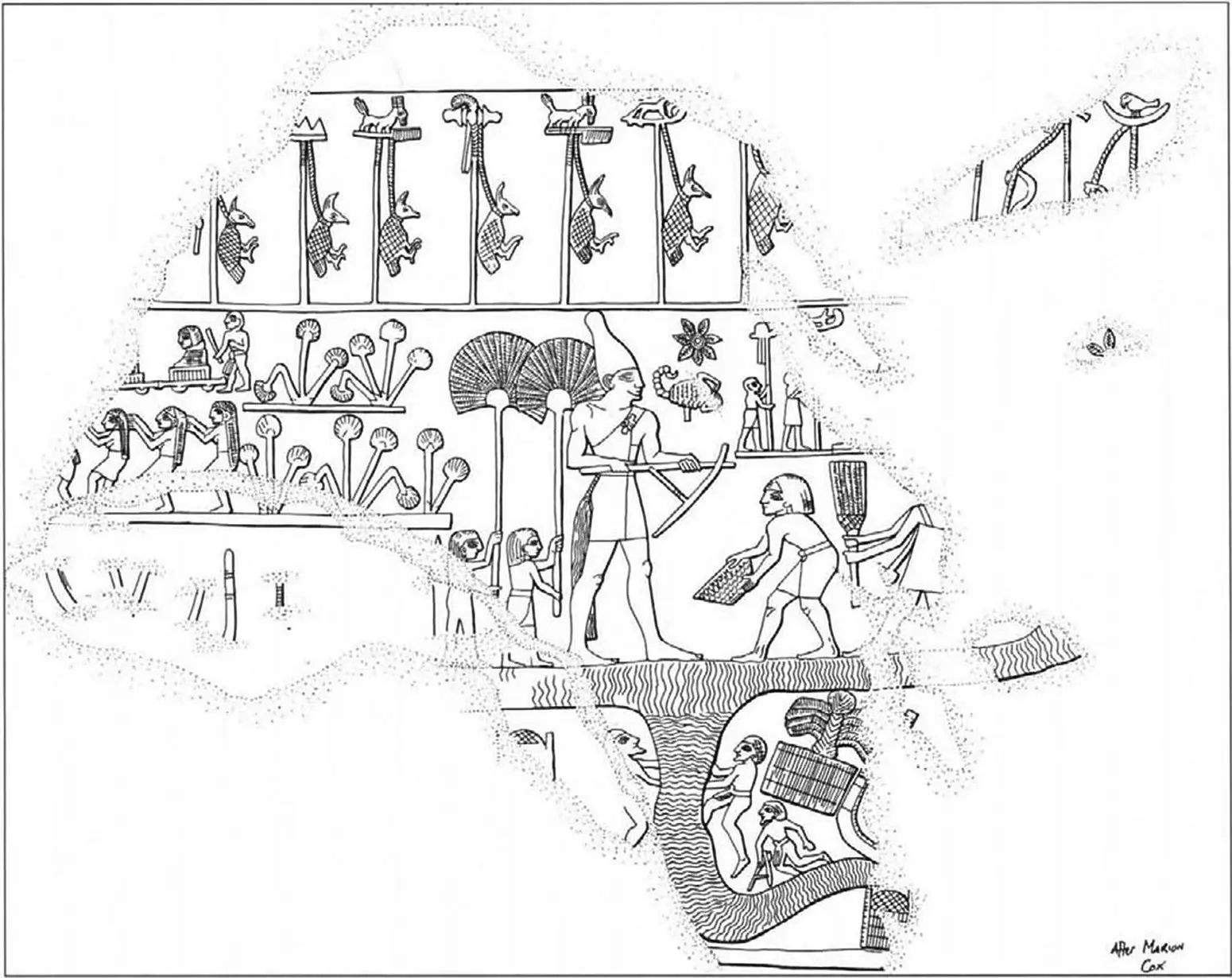

People could help the river by leading water in canals and building dykes around fields in order to regulate when the water reached the crops. Some of the earliest representations of kings from around 3000 may show such work ( Figure 1.8), but they do not constitute major projects to extend agricultural zones substantially. Artificial irrigation that used canals and basins to store and guide the water into areas that the river could not reach only appeared later in Egyptian history, and scholars debate when exactly it started. Probably the increased aridity in the later 3rd millennium pushed people into controlling the water more. Most important was the management of water in the Fayyum depression; during the Middle Kingdom and especially in Greek and Roman times, the state dug extensive canals to drain excess water and lead it to otherwise infertile sectors. Irrigation practices throughout Egypt basically remained the same for most of ancient history until the Romans introduced the waterwheel.

Figure 1.8 A 25‐cm‐high ceremonial mace head carved in limestone depicts a king, identified as Scorpion by the sign in front of his face, apparently digging an irrigation canal with a hoe, surrounded by attendants. On top of the image are standards that symbolize various regions of Egypt, with its inhabitants symbolized by birds dangling from a noose as a sign of subjection. The object dates to ca. 3000 bc and was excavated in Hierakonpolis. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Drawing by Richard Parkinson.

Source: Almendron

The most extensive remains of the 4th millennium are cemeteries, including a massive one with some 3000 tombs at the site of Naqada in Upper Egypt. This site gave its name to the archaeological culture that characterizes the last centuries of Egyptian prehistory. Scholars subdivide the Naqada period into I (3800–3550), II (3550–3200), and III (3200–2900), with further subdivisions (IIIA, IIIB, etc.) to acknowledge changes in the material culture. The changes were gradual and the period divisions do not necessarily reflect major cultural differences. The archaeological periodization is thus a chronological framework within which historical processes need to be situated, not a principle by which to understand the processes.

The earliest Naqada burials show the beginnings of later Egyptian practices. The dead are facing west and gifts are set beside them. The manner of burial and the quality and quantity of grave goods demonstrate the changes in Egyptian society best. At first corpses were just placed in shallow pits, but over time the treatment of some bodies became much more elaborate. In Naqada II the first evidence of wrapping them with linen appears, which would ultimately lead to full mummification by the 4th dynasty. Tomb structures came to signal social distinction. While the majority of people remained buried in simple pits, some tombs became large and complex and after 3200 would develop into major constructions with multiple chambers and, for some, a superstructure that marked them clearly in the landscape. The larger tombs were surrounded by smaller and simpler ones, probably in which to bury people who had served the central tomb’s owner in life. The grave goods accompanying the dead most clearly show how people’s wealth started to differ substantially. While the majority received a few pots, next to the bodies of some individuals were placed objects such as stone mace heads and palettes (flat slabs seemingly used to mix cosmetic paints) carved in the shapes of birds and animals. The distinctions between burials increased over time, which must reflect differences in wealth and status of the living. These processes of social differentiation would culminate in late prehistory and lead to the development of the Egyptian state.

While Naqada I was a regional culture, Naqada II remains appeared throughout Upper Egypt. It is clear that larger settlements existed near the cemeteries, and those at Naqada, Hierakonpolis, and Abydos were the most prominent. One tomb in Hierakonpolis, tomb 100, was especially impressive because of its painted wall decoration, which displayed boats, animals, and fighting men. A man is depicted holding two lions with his bare hands, an artistic motif that scholars interpret as a sign that the buried person was a leader of the community. Archaeological assemblages show that the inhabitants of the Delta still adhered to a different culture, which we call Ma’adi, although they exchanged goods with Upper Egypt. They had close contacts with Palestine and imported copper from there as well as highly prized goods from farther afield, such as lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. They traded some of these commodities on to Upper Egypt.

Special Topic 1.2 Egyptian city names

Thebes, Hierakonpolis, Memphis … We do not refer to cities with their ancient Egyptian names, but mostly with Greek designations. The Greeks used several ways to formulate the names of places in Egypt. When a city was most famous as the center of worship of an Egyptian god, they regularly named it after a manifestation of that god, often the animal form. Hierakonpolis meant “the city of the falcon” because it was a cult center of the god Horus, who was represented as a falcon. The Egyptian name was Nekhen. Heliopolis was “the city of the sun,” after the sun god; its Egyptian name was Iunu.

The Greeks could base their names on ancient Egyptian designations of an entire city or an important structure within it, and they tried to imitate the original sound. Such names sometimes replicated those of cities in Greece itself. Egyptian Abedju became Abydos, a city name also found in northern Greece. Memphis, the city near the pyramids in the north, derived its name from Mennufer, King Pepy I’s pyramid at Saqqara (a modern Arabic name that derives from Sokar, the god of the necropolis). In late Egyptian language Mennufer became Memfe, which the Greeks rendered as Memphis. The Egyptians also referred to the city as Ankh‐tawy, “The Life of the Two Lands,” because of its location at the junction of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Читать дальше