§ 5. Ecclesiastical Organisation

While in all ancient monarchies religion and sacerdotalism were a political as well as a social power, the position of the Christian Church in the Roman Empire was a new thing in the world, presenting problems of a kind with which no ruler had hitherto been confronted and to which no past experience offered a key. The history of the Empire would have been profoundly different if the Church had remained as independent of the State as it had been before Constantine, and if that Emperor and his successors had been content to throw the moral weight of their own example into the scale of Christianity and to grant the Church the same freedom and privileges which were enjoyed by pagan cults and priesthoods. But heresies and schisms and religious intolerance on one side, and the despotic instinct to control all social forces on the other, brought about a close union between State and Church which altered the character and spirit of the State and constituted perhaps the most striking difference between the early and the later Empire. The disorders caused by violent divisions in the Church on questions of doctrine called for the intervention of the public authorities, and rival sects were only too eager to secure the aid of the government to suppress their opponents. Hence at the very beginning Constantine was able to establish the principle that it devolved upon the Emperor not indeed to settle questions of doctrine at his own discretion, but to summon general ecclesiastical Councils for that purpose and to preside at them. The Council of Arles (A.D. 314) was convoked by Constantine, and the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea exhibited the full claim of the Emperor to be head of the Church. But in this capacity he stood outside the ecclesiastical hierarchy; he assumed no title or office corresponding to that of Pontifex Maximus. Historical circumstances decided that this league of Church and State should develop on very different lines in the east and in the west. In the west it was to result in the independence and ultimately in the supremacy of the Church; in the east the Church was kept in subordination to the head of the State, and finally ecclesiastical affairs seem little more than a department of the Imperial Government. Even in the fourth century the bishop of Rome has a more independent position than the bishop of Constantinople.

At the beginning of our period the general lines of ecclesiastical organisation had been completed. The clergy were graded in a hierarchical scale of seven orders — bishops, priests, deacons, subdeacons, acolytes, exorcists, and readers. In general, the ecclesiastical divisions closely correspond to the civil. 119Every city has its bishop. Every province has its metropolitan, who is the bishop of the metropolis of the province. And above the provincial metropolitans is the exarch, whose jurisdiction corresponds to the civil diocese. A synod of bishops is held annually in each province.

But among the more important sees, four stood out pre-eminent — Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch. Of these Rome was acknowledged to be the first, but there was rivalry for the second place. Besides these the See of Jerusalem had, by virtue of its association with the birth of Christianity, a claim to special recognition. By the middle of the fifth century the positions of these great sees were defined, and their jurisdiction fixed. Their bishops were distinguished as Patriarchs, 120though the bishop of Rome did not assume this title. The ecclesiastical map shows five great jurisdictions or Patriarchates. The authority of Rome extended over the whole western or Latin half of the Empire, and included the Praetorian Prefecture of Illyricum. 121The Patriarchate of Constantinople ultimately embraced the civil dioceses of Thrace, Pontus, and Asia. 122The Patriarchate of Alexandria, third in precedence, corresponded to the Diocese of Egypt. The Patriarchate of Antioch comprised the greater part of the Diocese of the East; the small Patriarchate of Jerusalem the three Palestinian provinces. The autocephalous Church of Cyprus stood apart and independent. 123

The development of a graded hierarchy among the bishops revolutionised the character of the Church. For three centuries the Christian organisation had been democratic. Its union with the monarchical state changed that. The centralised hierarchical system enabled the Emperors to control it in a way which would have been impossible if the old democratic forms had continued.

Constantine and his successors knew how to attach to themselves the powerful organisation of which they had undertaken the direction. Valuable privileges were conceded to the clergy and the churches. Above all, the clergy, like the pagan priests, were exempted from taxation, 124a privilege which attracted many to their ranks. The churches had an unrestricted right of receiving bequests, and they inherited from the pagan temples the privilege of affording asylum. 125The bishops received the right of acting as judges in civil cases which the parties concerned agreed to bring before them, and their decisions were without appeal. 126It was the Imperial policy to make use of the ecclesiastical authorities in local administration, and as the old life of the urban communities declined the influence of the bishops increased. The bishop shared with the defensor civitatis the duty of protecting the poor against the oppression of the powerful and the exactions of government officials, and he could bring cases of wrongdoing to the ears of the Emperor himself. Ultimately he was to become the most influential person in urban administration.

The first century of Christianity in its new rôle as a state religion was marked by the development of ecclesiastical law. The canons of the Council of Nicaea formed a nucleus which was enlarged at subsequent councils. The first attempt to codify canon law was made at the beginning of the fifth century. The legislation of councils was of course only binding on the Church as such, but as time went on it became more and more the habit of the Emperors to embody ecclesiastical canons in Imperial constitutions and thus make them part of the law of the state. It is, however, to be noticed that canon law exerted little or no effect upon the Roman civil law before the seventh century.

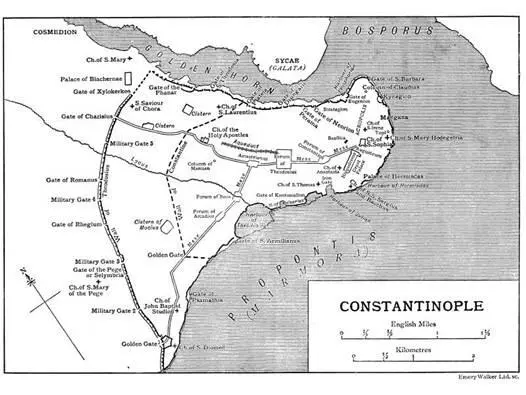

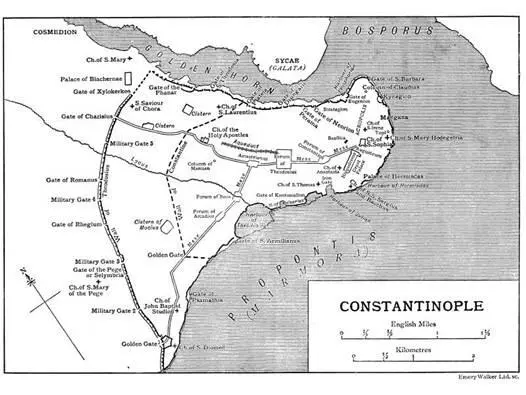

CHAPTER III: CONSTANTINOPLE

§ 1. Situation, Walls, and Harbours

THE history of a thousand years approved the wisdom of Constantine in choosing Byzantium for his new capital. A situation was needed from which the Emperor could exercise imminent authority over south-eastern Europe and Asia, and could easily reach both the Danube and the Euphrates. The water passage where Asia and Europe confront each other was one of the obvious regions to be considered in seeking such a central site. Its unique commercial advantages might have been alone sufficient to decide in its favour. It was the natural meeting-place of roads of trade from the Euxine, the Aegean, and northern Europe. When he determined to found his city by this double-gated barrier between seas and continents, there were a few sites between which his choice might waver. But there was none which in strategical strength could compare with the promontory of Byzantium at the entrance of the Bosphorus. It had indeed some disadvantages. The prevailing winds are north-easterly, and the arrival of sea-borne merchandise was often seriously embarrassed, a fact which the enemies of Constantine did not fail to insist on. 1The frequency of earthquakes 2was another feature which might be set against the wonderful advantages of Byzantium as a place for a capital of the Empire.

Читать дальше