Charles G. Harper

The Old Inns of Old England

A Picturesque Account of the Ancient and Storied Hostelries of England (Complete Edition: Vol. 1&2)

e-artnow, 2020

Contact: info@e-artnow.org

EAN: 4064066398958

Volume 1 Volume 1 Table of Contents CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII

Volume 2

Table of Contents Table of Contents Volume 1 Volume 1 Table of Contents CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII Volume 2

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTORY

The Old Inns of Old England!—how alluring and how inexhaustible a theme! When you set out to reckon up the number of those old inns that demand a mention, how vast a subject it is! For although the Vandal—identified here with the brewer and the ground-landlord—has been busy in London and the great centres of population, destroying many of those famous old hostelries our grandfathers knew and appreciated, and building in their stead “hotels” of the most grandiose and palatial kind, there are happily still remaining to us a large number of the genuine old cosy haunts where the traveller, stained with the marks of travel, may enter and take his ease without being ashamed of his travel-stains or put out of countenance by the modish visitors of this complicated age, who dress usually as if going to a ball, and whose patronage has rung the death-knell of many an inn once quaint and curious, but now merely “replete with every modern convenience.”

I thank Heaven—and it is no small matter, for surely one may be thankful for a good inn—that there yet remain many old inns in this Old England of ours, and that it is not yet quite (although nearly) a misdemeanour for the wayfarer to drink a tankard of ale and eat a modest lunch of bread and cheese in a stone-flagged, sanded rustic parlour; or even, having come at the close of day to his halting-place, to indulge in the mild dissipation and local gossip in the bar of an old-time hostelry.

This is one of the last surviving joys of travel in these strange times when you journey from great towns for sake of change and find at every resort that the town has come down before you, in the shape of an hotel more or less palatial, wherein you are expected to dine largely off polished marble surroundings and Turkey carpets, and where every trace of local colour is effaced. A barrier is raised there between yourself and the place. You are in it, but not of it or among it; but something alien, like the German or Swiss waiters themselves, the manager, and the very directors and shareholders of the big concern.

At the old-fashioned inn, on the other hand, the whole establishment is eloquent of the place, and while you certainly get less show and glitter, you do, at any rate, find real comfort, and early realise that you have found that change for which you have come.

But, as far as mere name goes, most inns are “hotels” nowadays. It is as though innkeepers were labouring under the illusion that “inn” connotes something inferior, and “hotel” a superior order of things. Even along the roads, in rustic situations, the mere word “inn”—an ancient and entirely honourable title—is become little used or understood, and, generally speaking, if you ask a rustic for the next “inn” he stares vacantly before his mind grasps the fact that you mean what he calls a “pub,” or, in some districts oftener still, a “house.” Just a “house.” Some employment for the speculative mind is offered by the fact that in rural England an inn is “a house” and the workhouse “ the House.” Both bulk largely in the bucolic scheme of existence, and, as a temperance lecturer might point out, constant attendance at the one leads inevitably to the other. At all events, both are great institutions, and prominent among the landmarks of Old England.

Which is the oldest, and which the most picturesque, inn this England of ours can show? That is a double-barrelled question whose first part no man can answer, and the reply to whose second half depends so entirely upon individual likings and preferences that one naturally hesitates before being drawn into the contention that would surely arise on any particular one being singled out for that supreme honour. Equally with the morning newspapers—and the evening—each claiming the “largest circulation,” and, like the several Banbury Cake shops, each the “original,” there are several “oldest licensed” inns, and very many arrogating the reputation of the “most picturesque.”

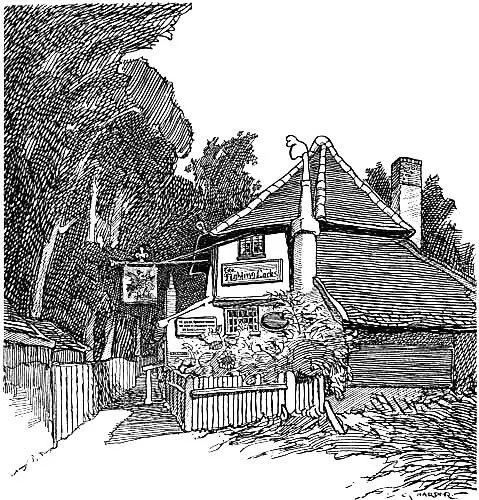

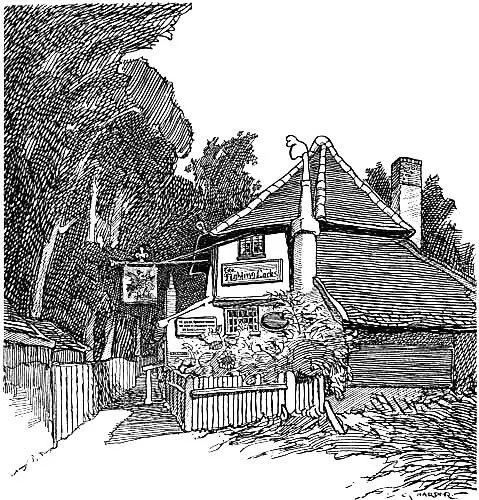

The “Fighting Cocks” inn at St. Albans, down by the river Ver, below the Abbey, claims to be—not the oldest inn—but the oldest inhabited house, in the kingdom: a pretension that does not appear to be based on anything more than sheer impudence; unless, indeed, we take the claim to be a joke, to which an inscription,

The Old Round House,

Rebuilt after the Flood,

formerly gave the clue. But that has disappeared. The Flood, in this case, seeing that the building lies low, by the river Ver, does not necessarily mean the Deluge.

This curious little octagonal building is, however, of a very great age, for it was once, as “St. Germain’s Gate,” the water-gate of the monastery. The more ancient embattled upper part disappeared six hundred years ago, and the present brick-and-timber storey takes its place.

THE OLDEST INHABITED HOUSE IN ENGLAND: THE “FIGHTING COCKS,” ST. ALBANS.

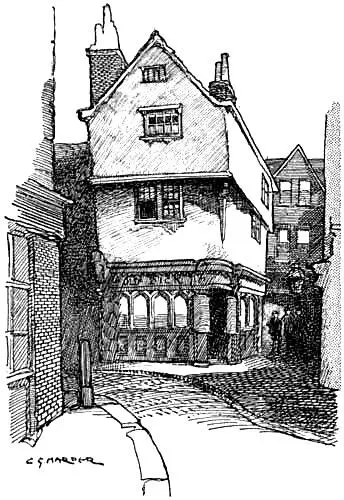

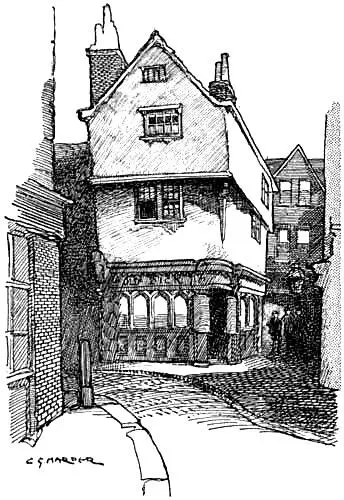

The City of London’s oldest licensed inn is, by its own claiming, the “Dick Whittington,” in Cloth Fair, Smithfield, but it only claims to have been licensed in the fifteenth century, when it might reasonably—without much fear of contradiction—have made it a century earlier. This is an unusual modesty, fully deserving mention. It is only an “inn” by courtesy, for, however interesting and picturesque the grimy, tottering old lath-and-plaster house may be to the stranger, imagination does not picture any one staying either in the house or in Cloth Fair itself while other houses and other neighbourhoods remain to choose from; and, indeed, the “Dick Whittington” does not pretend to be anything else than a public-house. The quaint little figure at the angle, in the gloom of the overhanging upper storey, is one of the queer, unconventional imaginings of our remote forefathers, and will repay examination.

THE “DICK WHITTINGTON,” CLOTH FAIR.

Our next claimant in the way of antiquity is the “Seven Stars” inn at Manchester, a place little dreamt of, in such a connection, by most people; for, although Manchester is an ancient city, it is so modernised in general appearance that it is a place wherein the connoisseur of old-world inns would scarce think of looking for examples. Yet it contains three remarkably picturesque old taverns, and the neighbouring town of Salford, nearly as much a part of Manchester as Southwark is of London, possesses another. To take the merely picturesque, unstoried houses first: these are the “Bull’s Head,” Greengate, Salford; the “Wellington” inn, in the Market-place, Manchester; the tottering, crazy-looking tavern called “Ye Olde Rover’s Return,” on Shude Hill, claiming to be the “oldest beer-house in the city,” and additionally said once to have been an old farmhouse “where the Cow was kept that supplied Milk to The Men who built the ‘Seven Stars,’ ” and lastly—but most important—the famous “Seven Stars” itself, in Withy Grove, proudly bearing on its front the statement that it has been licensed over 560 years, and is the oldest licensed house in Great Britain.

Читать дальше