Not many records of travelling across England in the fourteenth century have survived. Indeed the only detailed one we have, and that is merely a return of expenses, surviving in Latin manuscript at Merton College, Oxford, concerns itself with nothing but the cost of food and lodging at the inns and the disbursements on the road, made by the Warden and two fellows who, with four servants—the whole party on horseback—in September, 1331, travelled to Durham and back on business connected with the college property. The outward journey took them twelve days. They crossed the Humber at the cost of 8 d. , to the ferry: beds for the entire party of seven generally came to 2 d. a night, beer the same, wine 1¼ d. , meat 5½ d. , candles ¼ d. , fuel 2 d. , bread 4 d. , and fodder for the horses 10 d.

Table of Contents

GENERAL HISTORY OF INNS

The mediæval hostelries, generally planned in the manner of the old galleried inns that finally went out of fashion with the end of the coaching age, consisting of a building enclosing a courtyard, and entered only by a low and narrow archway, which in its turn was closed at nightfall by strong, bolt-studded doors, are often said to owe their form to the oriental “caravanserai,” a type of building familiar to Englishmen taking part in the Crusades.

But it is surely not necessary to go so far afield for an origin. The “caravanserai” was originally a type of Persian inn where caravans put up for the night: and as security against robbers was the first need of such a country and such times, a courtyard capable of being closed when necessary against unwelcome visitors was clearly indicated as essential. Persia, however, and oriental lands in general, were not the only countries where in those dark centuries robbers, numerous and bold, or even such undesirables as rebels against the existing order of things, were to be reckoned with, and England had no immunity from such dangers. In such a state of affairs, and in times when private citizens were careful always to bolt and bar themselves in; when great lords dwelt behind moats, drawbridges, and battlemented walls; and when even ecclesiastic and collegiate institutions were designed with the idea that they might ultimately have to be defended, it is quite reasonable to suppose that innkeepers were capable of evolving a plan for themselves by which they and their guests, and the goods of their guests, might reckon on a degree of security.

This was the type of hostelry that, apart from the mere tavern, or alehouse, remained for so many centuries typical of the English good-class inns. It was at once, in a sense—to compare old times with new—the hotel and railway-station of an age that knew neither railways nor the class of house we style “hotel.” It was the fine flower of the hostelling business, and to it came and went the carriers’ waggons, the early travellers riding horseback, and, in the course of time, as the age of wonderful inventions began to dawn, the stage and mail-coaches. Travellers of the most gentle birth, equally with those rich merchants and clothiers who were the greatest travellers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, inned at such establishments. It was at one such that Archbishop Leighton ended. He had said, years before, that “if he must choose a place to die in, it should be an inn, it looking like a pilgrim’s going home, to whom this world was an inn, and who was weary of the noise and confusion of it.” He died, that good and gentle man, at the “Bell” in Warwick Lane, in 1684.

London, once rich in hostelries of this type, has now but one. In fine, it is not in the metropolis that the amateur of old inns of any kind would nowadays seek with great success; although, well within the memory of most people, it was exceptionally well furnished with them. It was neither good taste nor good business that, in 1897, demolished the “Old Bell,” Holborn, a pretty old-world galleried inn that maintained until the very last an excellent trade in all branches of licensed-victualling; and would have continued so to do had it not been that the greed for higher ground-rent ordained the ending of it, in favour of the giant (and very vulgar) building now occupying the spot where it stood. That may have been a remunerative transaction for the ground-landlord; but, looking at these commercial-minded clearances in a broader way, they are nothing less than disastrous. If, to fill some private purses over-full, you thus callously rebuild historic cities, their history becomes merely a matter for the printed page, and themselves to the eye nothing but a congeries of crowded streets where the motor-omnibuses scream and clash and stink, and citizens hustle to get a living. History, without visible ancient buildings to assure the sceptical modern traveller that it is not wholly lies, will never by itself draw visitors.

Holborn, where the “Old Bell” stood, was, until quite recent years, a pleasant threshold to the City. There stood Furnival’s Inn, that quiet quadrangle of chambers, with the staid and respectable Wood’s Hotel. Next door was Ridler’s Hotel, with pleasant bay-window looking upon the street, and across the way, in Fetter Lane, remained the “White Horse” coaching inn; very much down on its luck in its last years, but interesting to prowling strangers enamoured of the antique and out-of-date.

The vanished interest of other corners in London might be enlarged upon, but it is too melancholy a picture. Let us to the Borough High Street, and, resolutely refusing to think for the moment of the many queer old galleried inns that not so long since remained there, come to that sole survivor, the “George.”

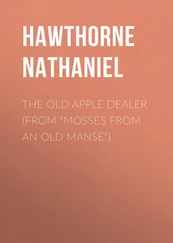

You would never by mere chance find the “George,” for it has no frontage to the street, and lies along one side of a yard not at first sight very prepossessing, and, in fact, used in these days for the unsentimental purposes of a railway goods-receiving depot. This, however, is the old yard once entirely in use for the business of the inn.

The “George,” as it now stands, is the successor of a pre-Reformation inn that, formerly the “St. George,” became secularised in the time of Henry the Eighth, when saints, even patron saints, were under a cloud. It is an exceedingly long range of buildings, dating from the seventeenth century, and in two distinct and different styles: a timbered, wooden-balustraded gallery in two storeys, and a white-washed brick continuation. The long ground-floor range of windows to the kitchen, the bar, and the coffee-room, is, as seen in the illustration, protected from any accidents in the manœuvring of the railway waggons by a continuous bulkhead of sleepers driven into the ground. It is pleasing to be able to bear witness to the thriving trade that continues to be done in this sole ancient survivor of the old Southwark galleried inns, and to note that, however harshly fate, as personified by rapacious landlords, has dealt with its kind, the old-world savour of the inn is thoroughly appreciated by those not generally thought sentimental persons, the commercial men who dine and lunch, and the commercial travellers who sleep, here.

But, however pleasing the old survivals in brick and stone, in timber and plaster, may be to the present generation, we seem, by the evidence left us in the literature and printed matter of an earlier age, to have travelled far from gross to comparatively ideal manners.

THE LAST OF THE OLD GALLERIED INNS OF LONDON: THE “GEORGE,” SOUTHWARK.

Photo by T. W. Tyrrell.

Читать дальше