The Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368): China under Mongol Rule

For close to four out of the next six centuries, Han Chinese would be under non‐Han rule: The Yuan Dynasty was Mongol, the Qing Dynasty was Manchu, and only the Ming Dynasty that came between was Han Chinese. Historically China’s troubles with non‐Han neighbors go back to at least 770 BCE, when the Zhou Dynasty moved its capital east to Luoyang, away from invading barbarians. The Han Dynasty also suffered the same humiliation, also relocating its capital eastward away from marauders. The Han Dynasty collapsed in large measure because it failed to deal with the northern frontier, and for the next 350 years China experienced invasions from the north. The reunification of the country by the Sui and Tang Dynasties required a strong military, but renegade generals became a domestic problem. To rein in the military meant sacrificing some of the nation’s ability to keep the northern frontier peoples in check. Accordingly, when the Song Dynasty came to power it never took control of the numerous frontier tribes. Eventually the Song retreated south and one of those tribes, the Mongols, swept the Song away.

The “Four Great Inventions”

1 The compass. Chinese had known that iron magnets had the quality of pointing the north‐south orientation as far back as the Warring States period (476–221 BCE). They made magnetized iron spoons and needles to use as compasses. The Song troops used compasses to determine direction at night and in heavy fog. Later, oceangoing ships adopted it. Arab merchants who often traveled on Chinese ships introduced it to Europe, thereby helping Europeans in their global exploration.

2 Gunpowder. Ancient Daoist alchemists, in their pursuit of a drug that would bring eternal life, had discovered that applying heat to a mixture of nitrate, sulfur, and charcoal would produce an explosion. The mixture was soon widely used to make fireworks. By late Tang, however, this mixture was used as gunpowder: Attached to the head‐end of an arrow, it was projected into the enemy camp to start a fire. It became widely employed in warfare in early Song. Further advances were made in its weaponization in the Song and Yuan Dynasties. A sophisticated formula for manufacturing gunpowder was recorded in an encyclopedic military book, Wujing Zongyao, in 1044. A tubular “fire cannon” was invented in 1259: It had a length of bamboo as the gun barrel, which was filled with gunpowder and projectiles. When lit, the gunpowder would explode, hurtling the projectiles at the enemy. Iron and copper tubes replaced the fragile bamboo barrels in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties (thirteenth to fourteenth centuries). It became the main weapon of the army in the Qing Dynasty.

3 3–4. Paper‐making technology and movable‐type printing. China had a long tradition of inscribing characters on flat bones, bronzeware, woodblocks, and stone slabs and pillars. Later, characters were written on strips of wood, bamboo, or silk. Cai Lun (61–121), a eunuch in the Han Dynasty, invented the technology of making paper from plant fiber (105). Henceforth, Chinese would write on paper with a writing brush and ink. In Tang, people began woodblock printing: cutting the characters of texts into woodblocks and printing them off on paper. Commoner Bi Sheng (?–1051) is credited with the invention of movable‐type printing in the Song Dynasty (1041). In this new method, one single character is cut into one single clay cube, and the clay cube is then hardened through baking. Since each tiny cube bears only one single character, the printer can use the same piece of type in different arrangements to print different texts. Going from woodblock printing to movable‐type printing was a big step forward. To print texts with movable types on paper greatly facilitated the dissemination of knowledge. Government documents, agricultural manuals, religious texts, and financial records could now be kept and transmitted with much greater ease, precision, and reliability. Unfortunately, Bi Sheng’s movable‐type printing was not widely adopted in China. (Metal movable‐type printing was invented in Korea in the early thirteenth century. Mechanical movable‐type printing was introduced to Europe in 1439 by German blacksmith, goldsmith, printer, and publisher Johannes Gutenberg [1398–1468].)

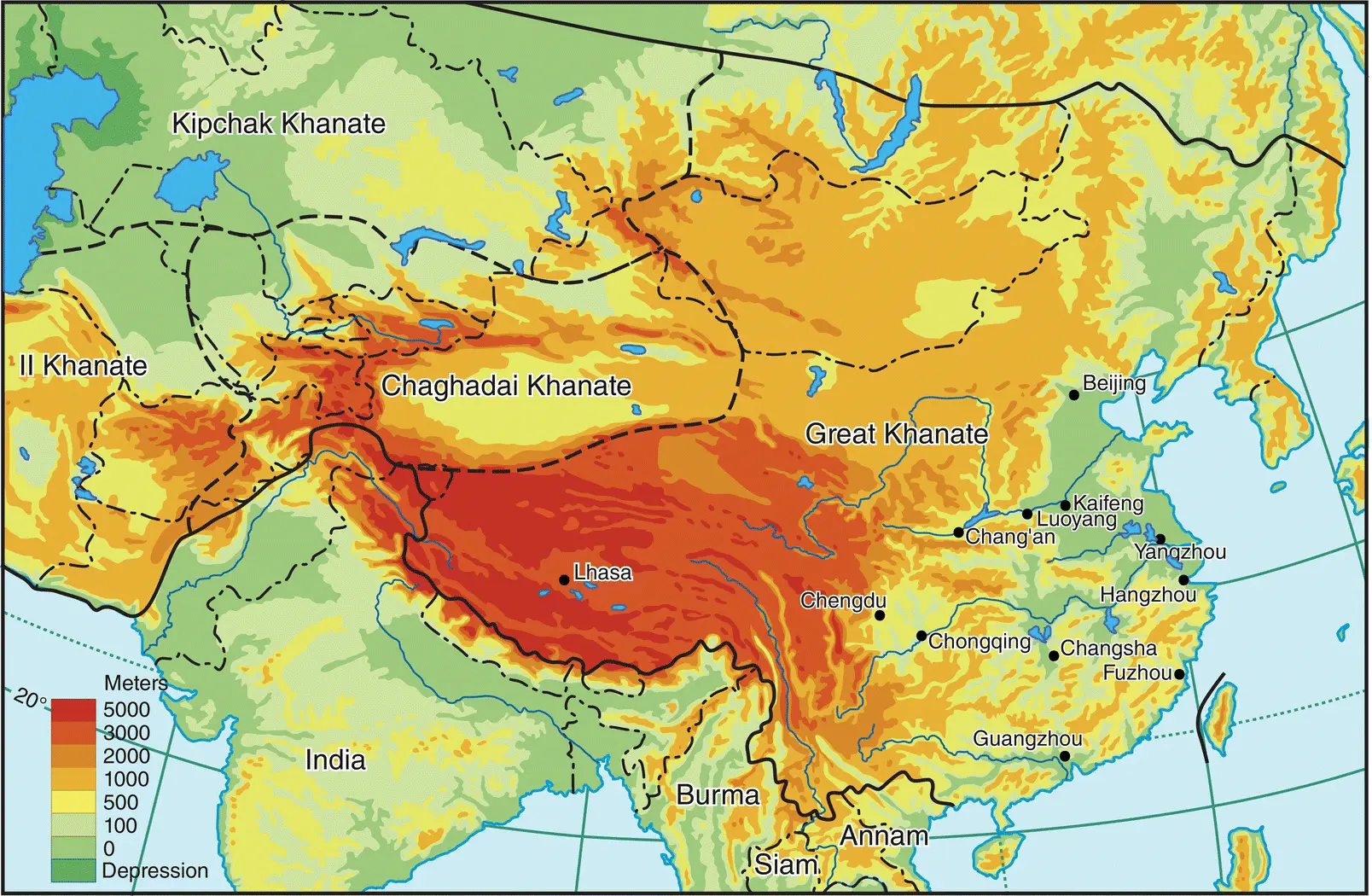

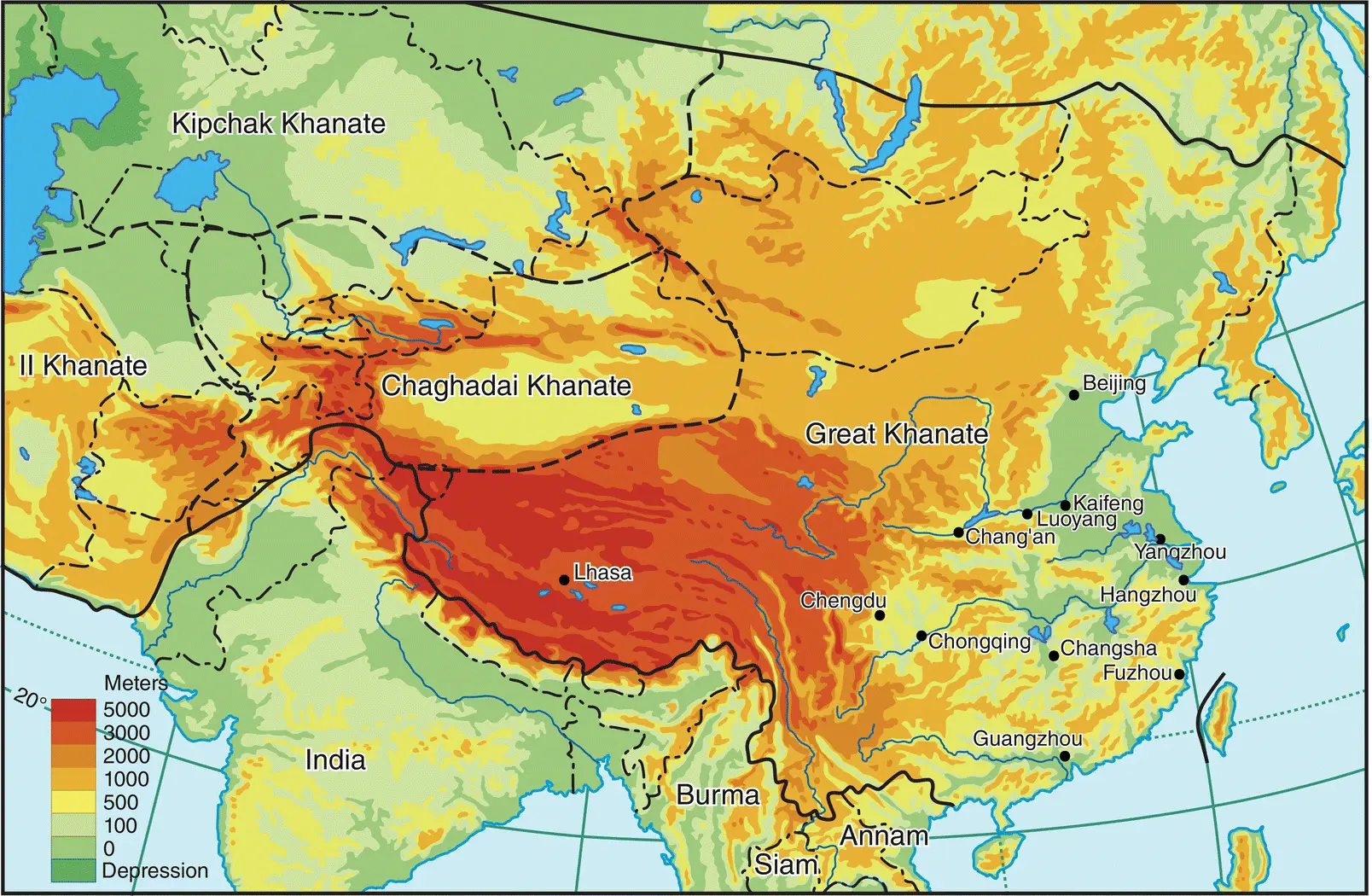

The Mongol Empire began with Genghis Khan (1162–1227), who united the various nomadic tribes on the Mongol steppes in 1206 and then launched out on his wars of global conquest. At its height, his empire straddled Eurasia, including today’s Mongolia, Iran, Russia, Poland, and Hungary. His grandson Kublai Khan (1216–1294) conquered China and Korea, and founded the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. He located his capital at Dadu (modern Beijing), close to his grassland home base in Mongolia. Yuan rule had some brilliant successes. The mere fact that it was part of a vast empire sprawling across the entirety of the Eurasian landmass enabled it to accomplish much that was unthinkable in other times.

Kublai Khan’s first challenge was how his tiny minority of Mongols would rule over a huge multiethnic population across such a large territory. His answer was a strategy of “divide and rule.” He divided the populations in China into four classes according to their ethnicity, and plugged them into an ethnically defined hierarchic structure. They were unequal as defined by law. The Mongols were perched at the top of the totem pole; the Muslims in the Mongol Empire ranked second to the top; the Han Chinese of North China made up the third class, which also included Khitans, Jurchens, and Koreans; and the Han Chinese of South China were assigned to the bottom of the pyramid as punishment for their long and stubborn resistance to Mongol conquest. The first two categories made up only 3% of the households in the empire, and the remaining two made up 97%.

Map of the four Mongol khanates.

Traditionally, the Mongols were organized into tribal units that included the military command, the civil government, and the civilian population. When they won a war, the commander would divide up the spoils of war among the tribal leaders, and reward them with grants of land; and the tribal leaders would then distribute the war booty among their followers. The nomadic victors naturally used the seized land as grazing land for raising their livestock. Since the early wars were generally fought between nomadic peoples, the change of hands of the land had no significant economic impact; the grazing land remained grazing land. But when the Mongols conquered China, the tradition had devastating consequences, for the land the Mongols seized was farmland, and the new masters readily converted it into pastureland. This had a twofold consequence. The Han Chinese farmers who lost their land lost their livelihood, and became a roaming population; the settled population of North China dropped by two‐thirds. This also hurt the Mongol government: It lost its potential agricultural tax revenues, and the roaming landless Han Chinese peasants were a tinderbox ready to explode anytime into peasant rebellion.

Yelu Chucai (1190–1244) was an advisor and prime minister to Genghis Khan. He came from an aristocratic ethnic Khitan family, but also had a thorough knowledge of Han Chinese practices. And he pointed out to the Khan that the Mongols’ long‐term interests depended on modifying their traditional nomadic ways and adopting the Chinese agricultural way of life. He urged the Khan to establish a civil government, make laws to ensure the civil government’s control over the land, keep Han farmers on the land, and collect agricultural taxes. The Khan was persuaded, but old habits were hard to break. The nomadic tradition of making land grants and then turning farmland into grazing land was never entirely abandoned. However, the government did make laws to encourage farming, and to protect farmland and farmers, and it issued detailed and informative agricultural manuals.

Читать дальше