For the next 20 centuries, Chinese rulers would all embrace a variable, eclectic mix of Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism. Although they may emphasize different elements of this mix, they would always discreetly call it Confucianism, for the brand name of Legalism had become taboo because of its blood‐stained association with Qin rule.

Emperor Liu Bang put his emphasis on Daoist restraint, for he understood that what the nation most needed after decades of Qin tyranny and war was a time for the people to recuperate and for the economy to recover. He wisely kept his government small and frugal, refrained from undertaking self‐aggrandizing construction projects, and avoided war with his neighbors. This emphasis on restraint enabled him to reduce taxes and labor service, which in turn gave the peasants a chance to live and toil peacefully on the land, and produce the wealth necessary to sustain a great empire. He set an example of government restraint and magnanimity. His successors in the early Han Dynasty followed his example. Together, they laid and institutionalized China’s political and intellectual foundations for the next two millennia.

As well, Emperor Liu Bang surrounded himself with men who had risen from the lower levels of society like himself and had contributed to the founding of his dynasty. But he soon suspected them of plotting against him, and cautiously removed them one by one from power. At the same time, he granted to members of his royal family the title of “prince” and private domains, hoping to consolidate his position through family support.

The Martial Emperor Han Wudi (Liu Che, 156–87 BCE) ascended to the throne when China was back on its feet—strong, prosperous, and stable. And he had a matching ambition: He envisioned himself as a highly active emperor ruling over a highly centralized empire of unprecedented wealth and power. He abandoned the earlier emphasis on restraint and frugality and redirect the nation toward greatness.

He needed a new state ideology to support his ambitious goals, and a prominent scholar of Confucianism, Dong Zhongshu (179–104 BCE), served up a new version of Confucianism. His theory of the “Grand Unity” claims that Heaven, the emperor, and humans form a hierarchic unity: Heaven is above the emperor, and the emperor is above all men. From this he extrapolates a fundamental rule for social behavior: The emperor dominates over his ministers, the father dominates over his sons, and the husband dominates over his wife. And his theory of “telepathy between Heaven and man” further claims that Heaven uses omens to inform the emperor of his evaluation of the latter’s performance. The Martial Emperor liked this new brew of philosophy and religion, made it the official state ideology, and relegated all other philosophies to a lower tier without banning them.

Dong’s theory of the Grand Unity established the supremacy of the Martial Emperor; his theory of telepathy gave Heaven an active role in human affairs, and encouraged the emperor to engage obsessively in elaborate rituals to ingratiate himself to Heaven; and the designation of Confucianism as the supreme ideology of the state ended the free competition of ideas on a level playing field, stifling Chinese thinking through the ages.

The Martial Emperor used his newly elevated status to demand uniformity in thinking. Few men who crossed him would survive. He also founded a state‐run university to train students in his version of Confucianism, and selected students who excelled to fill government posts. This institutional innovation led eventually to the creation of a system of imperial examinations for the selection of men for the civil service. Men selected through this process are known as scholar‐officials.

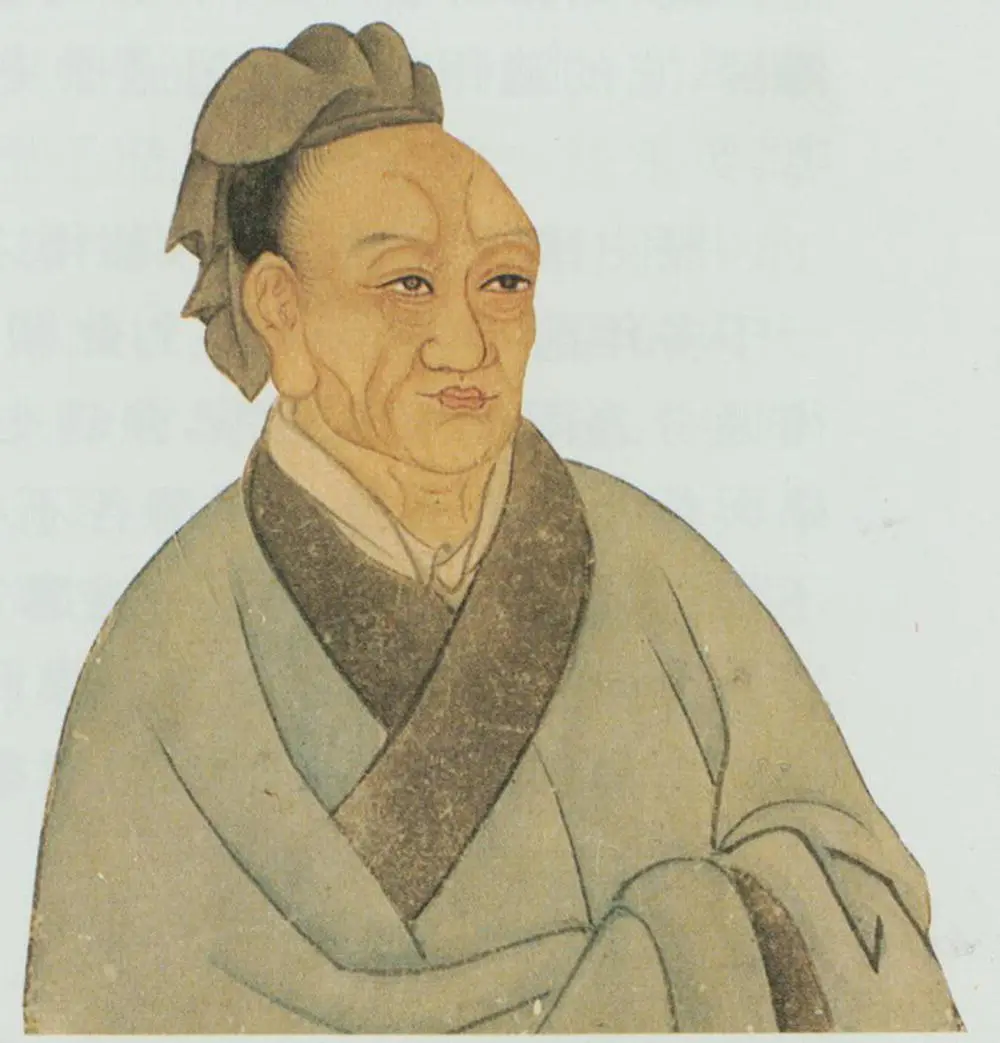

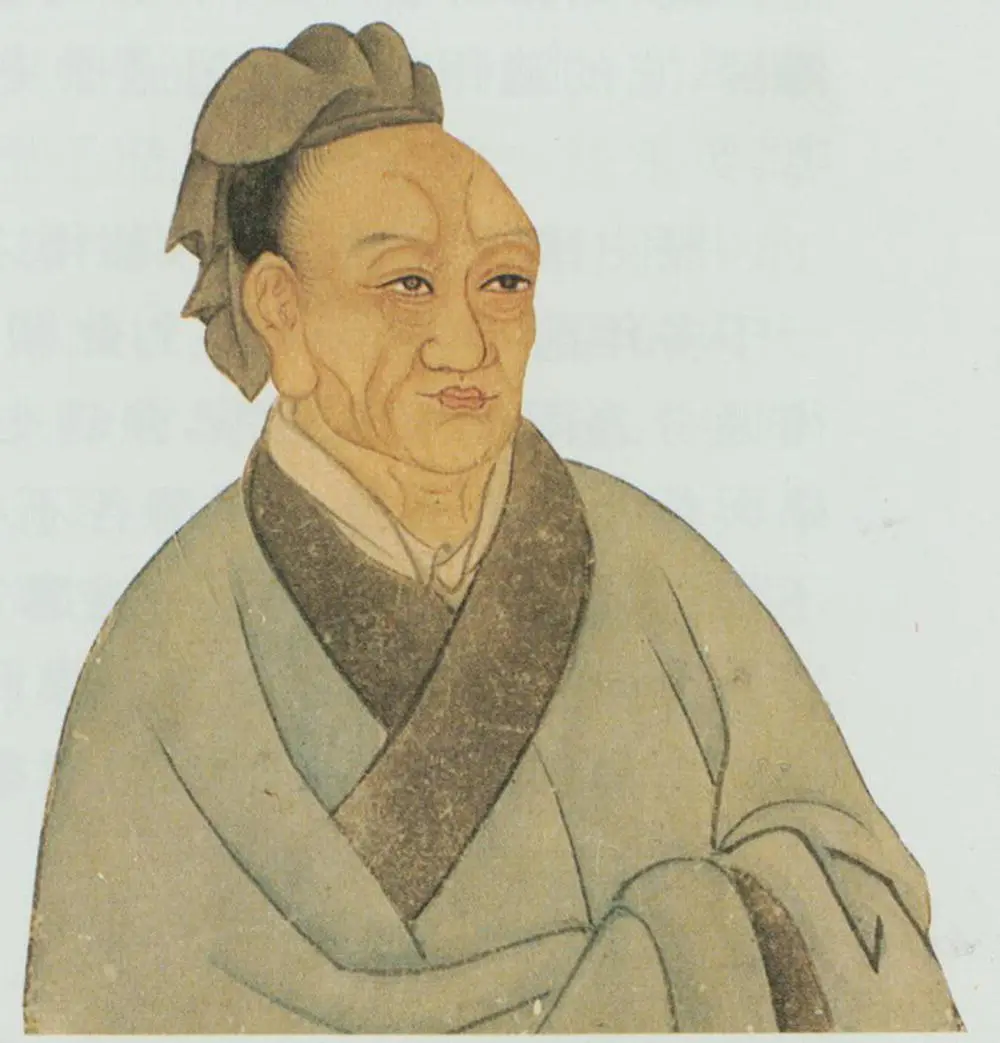

Sima Qian (ca. 145–86 BCE) was the greatest historian in Chinese history, yet the exact dates of his birth and death are lost to history. He was the Martial Emperor’s court historian and chief of the Imperial Secretariat. But when he dared to disagree with the emperor over an issue, the emperor condemned him to castration. Three years later, he was restored to his former official positions, but he had to live out his life in disgrace. Secretly, he focused his energies on writing China’s greatest historical work— Records of the Grand Historian . This 130‐volume work covers Chinese history from its mythological origins to the Han Empire of his day. It presents the past in biographies of men and women ranging from emperors to commoners, from great generals to merchants, craftsmen, and bandits, and from great scholars to outstanding entertainers. The biographies read like literature for their vivid character portrayal. Best of all, he makes every effort to use primary sources. He was so successful that later emperors would sponsor the writing of the histories of their own dynasties on the same model.

Sima Qian.

Source: Paul Fearn / Alamy Stock Photo.

At the time of the Han Dynasty’s founding, Emperor Liu Bang had granted the title of “prince” and private domains to men of the royal family. These expedient steps were taken from a position of weakness to gain their much‐needed support. But now that the Martial Emperor was in a position of strength, the princes’ autonomy had become an obstacle to his absolute rule. So he made laws to end their hereditary privileges: He reduced the size of their domains, stripped them of autonomy, and put government officials in charge of their jurisdiction. Simultaneously, he subjected government officials to the oversight of inspectors, and established a standing army under his direct control. The Martial Emperor, in a position of strength, had returned to the Qin model of absolute centralized power.

The nomadic Xiongnu tribes continued to pose a grave threat to China, despite Qin Shihuang’s earlier military victories over them. The Martial Emperor was determined to put an end to the threat once and for all. During his half‐century reign, he launched over a dozen wars and mobilized as many as 2 million troops against them. He adopted a new strategy of taking the fight to the Xiongnu in the boundless steppes and wiping them out. To do this, he sent envoys into Central Asia on the far side of the Xiongnu to persuade local tribes to enter trade relations and military alliances with China. In the first century CE, his troops successfully drove the Xiongnu tribes from China’s northern frontiers. One theory is that the fleeing Xiongnu became the Huns who later terrorized Europe.

The wars to defeat the Xiongnu led to the opening of the Silk Road. This was not a single road, but rather a sprawling network of routes that originated at the Han capital Chang’an, reached westward into modern Xinjiang Province, and continued to connect with Central Asia, India, North Africa, and Europe. It soon became a main artery across Eurasia, facilitating the exchange of commodities, people, and ideas. Much of the contact was indirect, with Persian merchants serving as the major intermediary. China’s main export was silk. To wear Chinese silk became a status symbol at the Roman court, and moralists there became alarmed at the way silk dresses revealed a woman’s curves. China’s main imports were horses, furs, aromatic spices, and jade from Central Asia; and iron, glass, and precious metals from Rome. Eventually China’s know‐how in making paper, printing with movable type, and manufacturing gunpowder was soon introduced to Central Asia and on to the West. The religions of Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity traveled eastward to China on this road as well.

The Martial Emperor also established government monopolies to control the manufacture and trading of salt and iron, thereby greatly expanding the role of government in the economic realm. In early Han, salt and iron were traded freely on the market, and taxed by the government. The merchants in the business became immensely wealthy. The Martial Emperor, in the meantime, was constantly running out of funds for his extended wars. So he set up government agencies that monopolized the trade, appointed experienced merchants to manage them, and funneled the profits into his war chest. He also set up a state agency to “buy high and sell low” in the marketplace in an effort to regulate market prices. These measures brought new revenues to his coffers, and had some effect at restraining big landowners and big merchants from manipulating the market to rip off the common people. But the system evolved to make very high officials and very big merchants ever richer at the expense of people at the middle and bottom of society. This accumulation of wealth at the higher end of society eventually reduced government revenues to the point where they could no longer sustain the Martial Emperor’s wars.

Читать дальше