1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...41 Life on the steppe consisted of constant battles. The most common clash pitted nomad against nature. The sky provided the most essential product, rainwater, without which animals and humans perished. The rain also made possible the feed that sustained animals and herders. This meant migration as either water or fodder became insufficient in a particular area. Heat, cold, and wind also habitually challenged human and animal existence. As bands moved around the steppe in search of shelter or provisions necessary for survival, they encountered other bands in search of the same, often resulting in violent clashes. Quite often as well, fighting among band members added to the list of brutality that bands characteristically suffered. And eventually, pastoral nomads and civilized cultures collided. Although the two different ways of life regularly interacted to their mutual benefit, usually involving trade, they also often clashed.

These struggles had many causes, including famine on the steppe or instability in civilized settings. Most civilizations employed terms of scorn to characterize their nomadic neighbors, the most common one being “barbarian.” Typically civilizations kept the nomads at bay, but occasionally nomads conquered and sometimes ruled their civilized neighbors. Life of the pastoral nomad changed very little from the introduction of the horse down to the twentieth century. The last emperor of the last dynasty in China was a Manchu, originally a pastoral nomadic/semi‐agrarian people from Manchuria, and their Manchu Qing Dynasty survived until 1912.

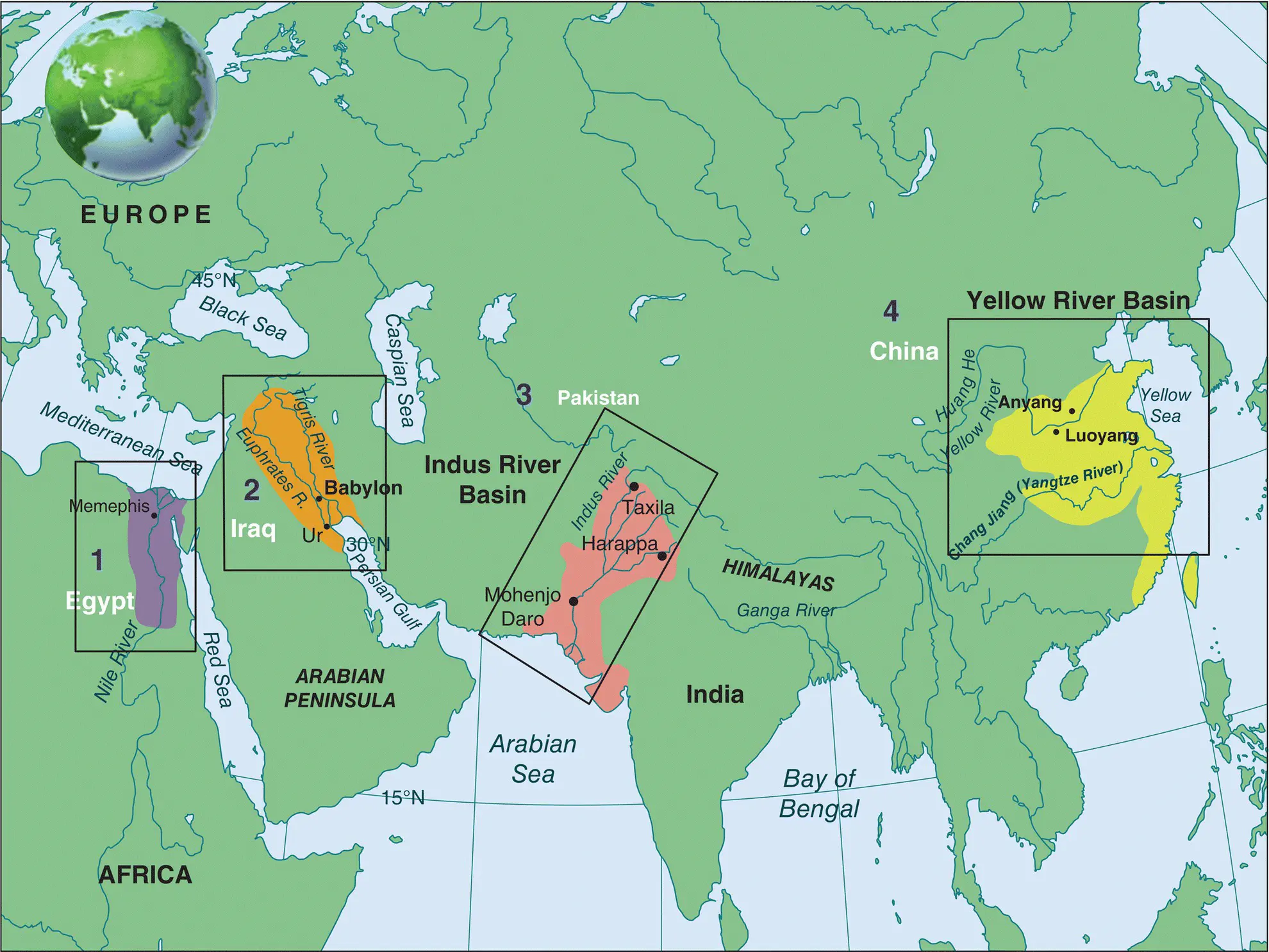

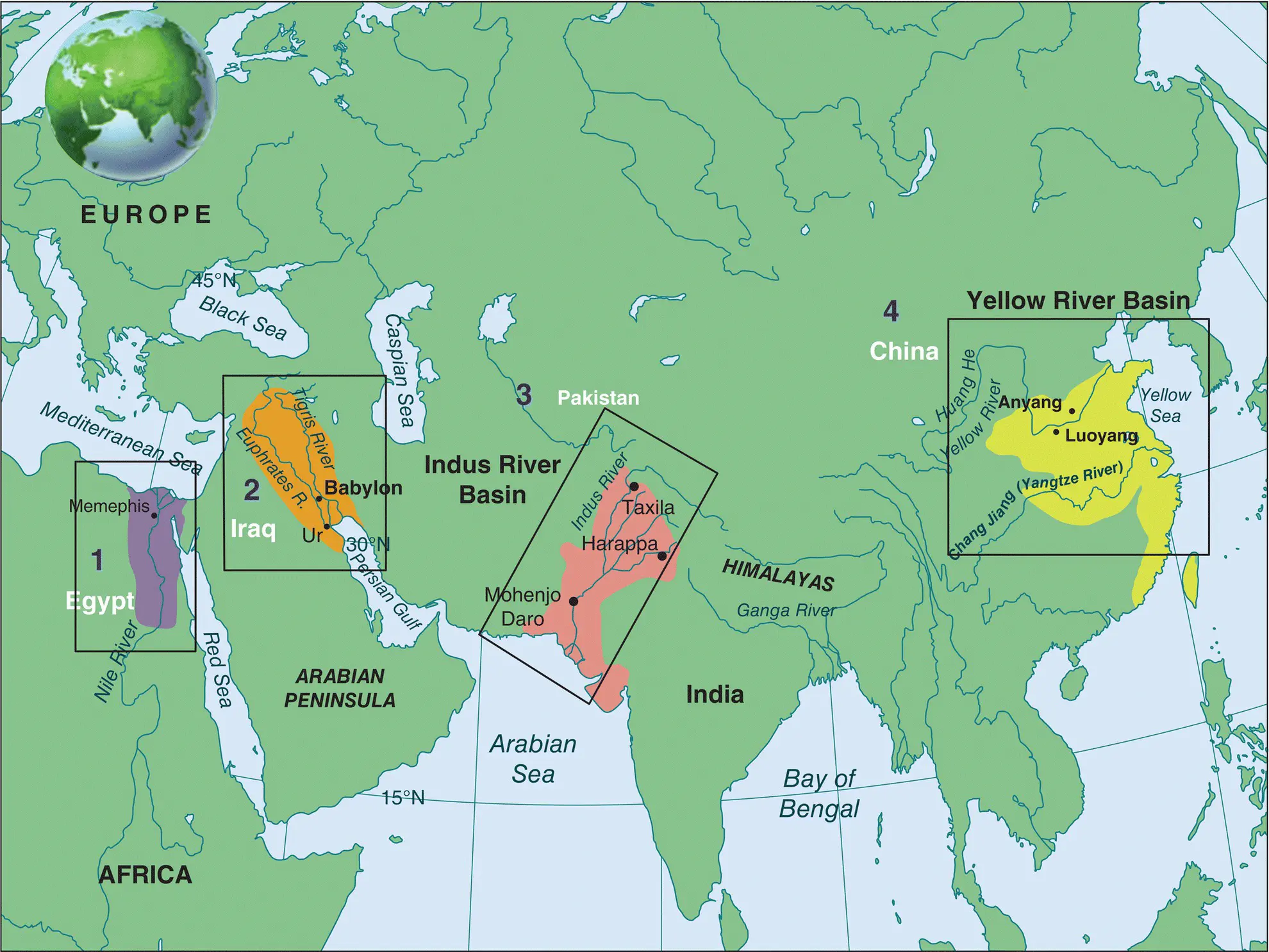

No one knows for sure where or when civilization began, but most historians would today agree that it did not originate in Asia east of Afghanistan. As it stands at present, city life probably began in either Mesopotamia or Egypt sometime just after 4000 BCE. Perhaps further archaeological research will one day unearth evidence of earlier urban life elsewhere, conceivably in India, China, or another Asian location. Based on current scholarship, evidence of civilization in India can be traced back to roughly 3000 BCE and in China to about 2000 BCE, and there are other possible but as yet unverifiable sites that may have developed civilized ways even earlier. But it is fairly clear that it began as a result of farmers being pushed to the margins of land where rainfall became unreliable. A lack of water produced a search for it, and all four early civilizations—Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China—emerged along rivers flowing through terrain with minimal annual rainfall. Irrigation solved the water problem, at least temporarily.

Four river valley civilizations.

What is civilization? Typically civilization includes a cluster of characteristics. It is urban; has rudimentary bureaucratic government that operates with the aid of writing; and can impose and collect taxes, provide for the community’s defense, and dictate the community’s common agenda. Whatever the program, it would be carried out by a society divided by specialization, the most significant cause of inequality. At the top of the hierarchy would be the political leader, usually a monarch of some kind, who would be assisted by bureaucratic advisors and be given leadership legitimacy by a priesthood. Below these elites, urbanites of every description provided all sorts of goods and services. Merchants, artisans, engineers, police, clerks, laborers, shamans, and other occupations emerged to meet the demands principally of their urban neighbors. Urbanites also serviced the needs and wants of the rural population, whose surplus agricultural output supported the city dwellers.

The farmers produced enough food surpluses to support the urban population chiefly because engineers made available an abundance of water via irrigation works. Not only did rivers provide water, enabling farming to occur in an arid or semi‐arid environment, but also these natural waterways regularly flooded, depositing fresh topsoil on farmland, thereby swelling the agricultural output. Moreover, the constant reinvigoration of the fields by routine flooding eliminated the farmer’s need to find new fertile fields. In the beginning, at least, civilized life seemed to generate win‐win situations. True, not everyone was relatively equal as in Paleolithic, Neolithic, or Pastoral Nomadic times, but during early Civilized times everyone’s standard of living had vastly increased. And as established civilizations developed and new civilizations emerged, ways of life within an urban culture produced a diversity of occupations and outlooks. The differences between civilizations also substantially diverged, producing distinctively remarkable uniqueness that resulted in some civilizations being more complex, prosperous, inventive, and enduring, while others either did less well or came to emulate many of the ways of their more successful neighbors. By the advent of Chinese civilization, some 25 to 35 million human beings inhabited the earth, most living in Asia. Only a small percentage of the world’s population lived in civilized cultures at that time. Gradually, however, most people would come to reside within the compass of Civilized societies, while Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Pastoral Nomadic peoples steadily became part of marginal ways of life.

Ancient Indian Civilization

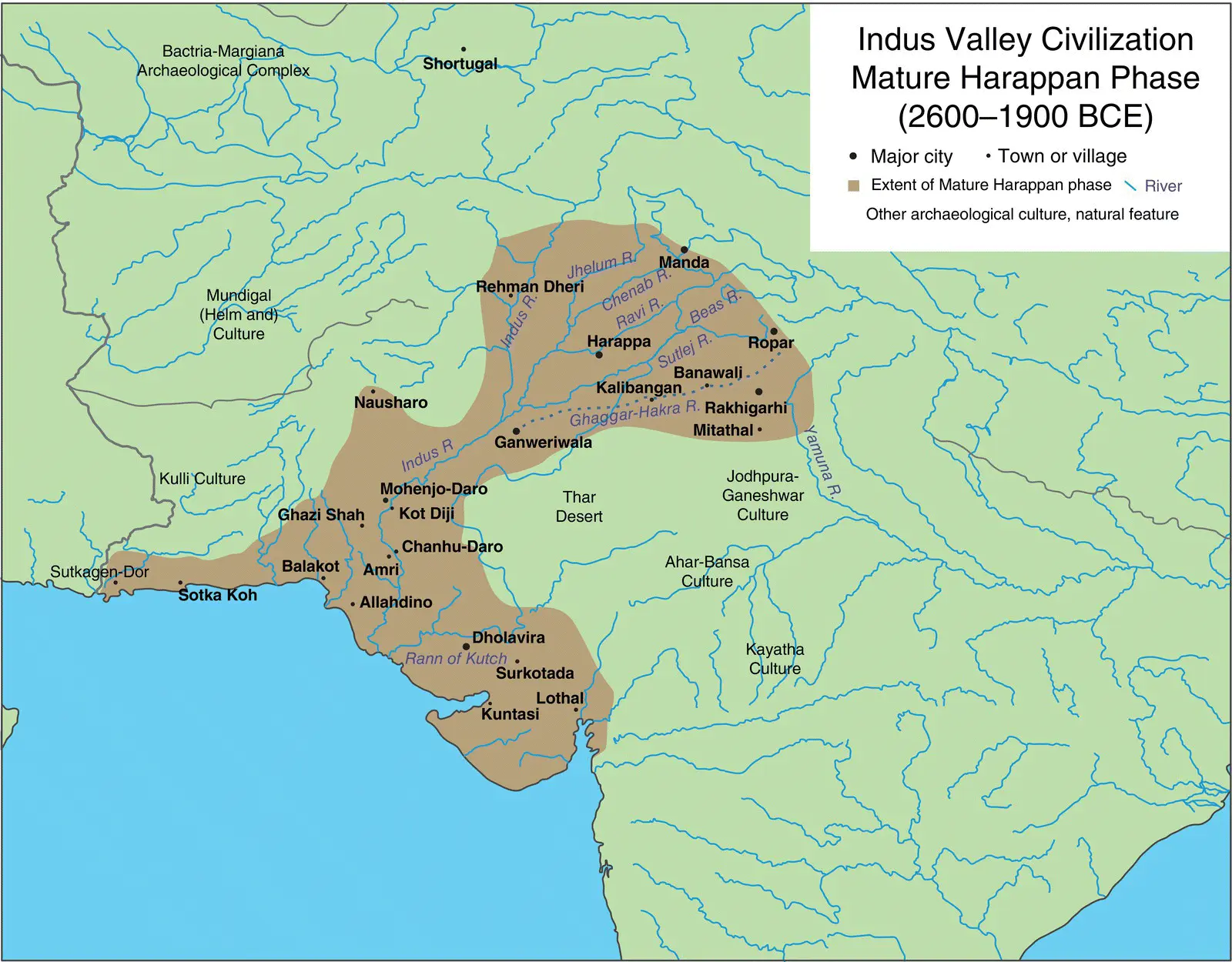

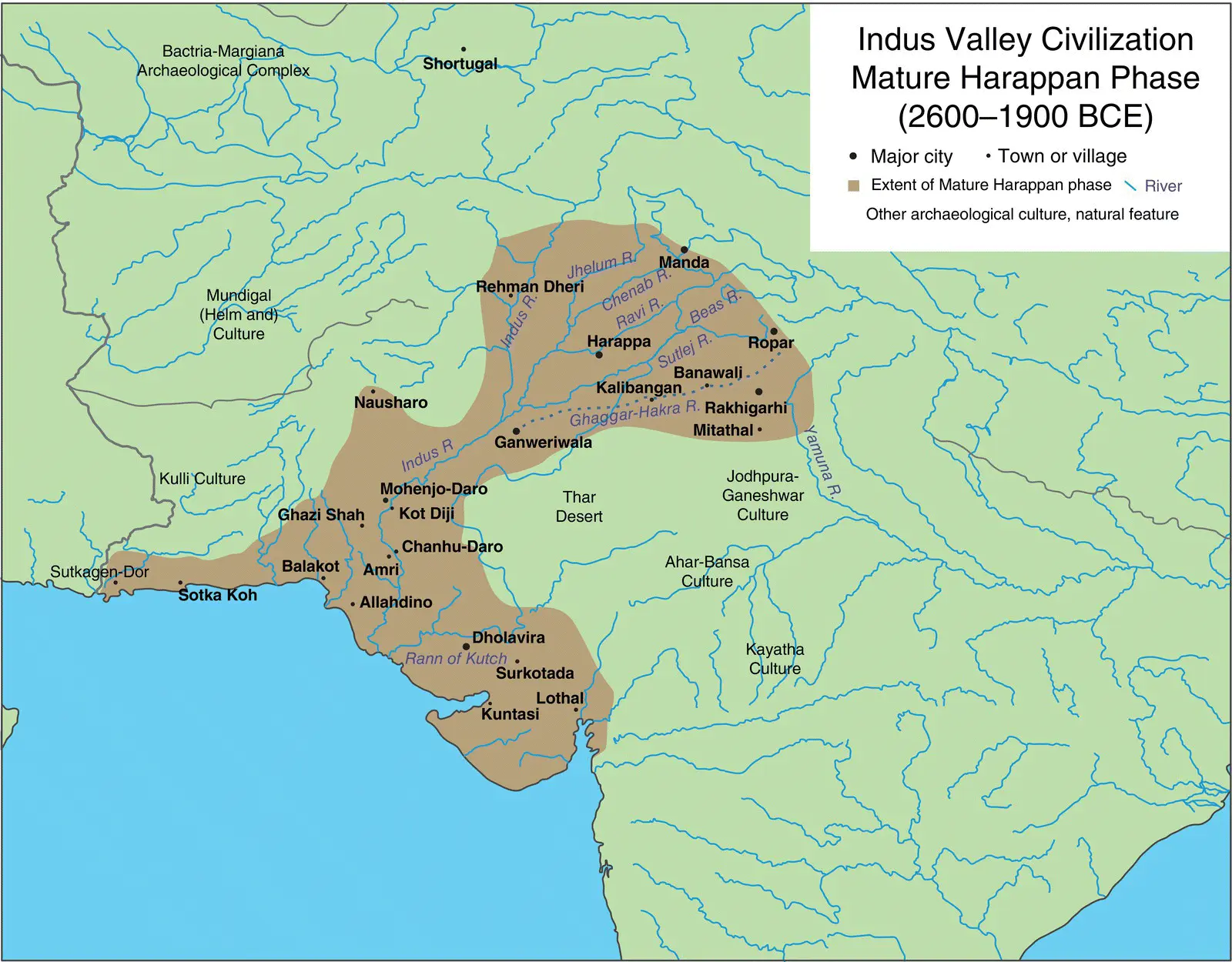

Academics still do not agree on which civilization in Asia possesses the longest continuous history. Certainly civilization in India began long before China’s, but did it continue unbroken down to the present? Indus Valley civilization, sometimes referred to as Harappan civilization and at times as Indus‐Saraswati civilization, originated about 3000 BCE along the Indus River and its tributaries in what is now Pakistan and northwestern India. It collapsed approximately 1500 BCE. Did the essence of that collapsed civilization continue to animate the subsequent Aryan culture of uncivilized, tribally organized people who entered India about that time from Central Asia and came to dominate India thereafter? Or did the Aryans basically create a civilization of their own with little or no input from the Harappan past? If the Harappan past fundamentally guides the Aryan future, then Indian civilization is continuous and thus longest. If not, China warrants the longevity distinction.

Indus Valley civilization, 2600–1900 BCE.

Source: McIntosh, Jane. (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives .

Evidence for civilization in ancient India, first hit upon in the mid‐nineteenth century, comes chiefly from archaeological excavations conducted in 1921 and 1922. These digs revealed two major cities whose origins date back to the third millennium BCE. Harappa, apparently the model for most other Indus Valley cities, was unearthed along the Ravi River, a tributary of the Indus in northern Pakistan. Mohenjo Daro, the second major site uncovered, was found along the Indus in southern Pakistan. Subsequent excavations have brought to light another 1500 sites, two‐thirds of which are along the now‐desiccated Saraswati River, and the oldest of which is Kalibangan, located in northwestern India. Given Indus Valley civilization’s proximity to the older Mesopotamian culture, the question of originality arises, since contact between the two existed. Here, too, whether Indus Valley civilization emerged on its own or owed its creation to outside influence will not likely be settled until the Harappan script is deciphered.

Читать дальше