Estas botas podían ser peludas o lonjeadas, es decir conservando o no el pelo. De conservar el pelo, quedaban muy vistosas si la pata del animal del que se sacó el cuero tenía manchas iguales. Era tal cantidad de caballos que pululaban en salvaje libertad, que el paisano se podía dar el lujo de tener para el invierno botas con pelo, que eran más abrigadas, y para el verano las lonjeadas, es decir limpias de pelo. Bien sobadas, se les daba forma usándolas. La punta (o boca) se dejaba abierta si el paisano estribaba “entre los dedos” (D).

De esta “bota abierta” se conocen dos formas: la que solo deja los dedos afuera y la de “medio pie”, la que, como su denominación indica, deja casi la mitad del pie a la vista. Era raro el paisano que anduviera descalzo, pero los había. Hasta las mujeres solían calzarse con botitas de potrillo. El zapato, en aquellos tiempos en que se veían obligadas a vivir lejos de toda población, era muy difícil de obtener.

Lucio V. Mansilla, en su Viaje al país de los ranqueles , refiriéndose a la hija de un cacique, dice:

“A falta de zapatos, le habían puesto unas botitas de potro, de cuero de gato” .

Como el paisano usaba estribo, y por lo tanto introducía la punta del pie en él, cerraba la boca de la bota, cosiéndola hacia adentro, dándole la forma del pie; o de lo contrario, se mojaba la punta y se doblaba hacia arriba o hacia abajo y se ataba fuertemente a la altura de los dos mayores. Una vez amoldada al pie, se hacía una costura pequeña. Luego se volvía la bota hacia afuera y la costura quedaba dentro, pero sin producir daño al pie.

La figura (E) muestra la punta de una bota cosida hacia adentro. Las formas de lucir las botas fueron variadas: eran los pequeños lujos del paisano, junto con otras pocas prendas de vestir, y sobre todo, el caballo y el apero. Su fantasía le llevó a elegir botas que tuvieran iguales manchas en el pelo. Había quien las usaba cortas de caña; otros la cortaban mucho más larga para luego, al colocárselas, dar vuelta la parte alta. A esta la llamaban “bota con delantal” (F). También solían cortar esos flecos en tiritas, dándoles una vistosa forma: la llamaban “delantal con flecos” (G). Si estos dos últimos tipos de botas eran con el pelo hacia afuera, la vuelta o delantal quedaba blanco por ser la zona lonjeada.

Otro lujo que se podía dar el paisano era el calzoncillo cribado, que se usó mucho hasta el último cuarto del siglo xix. Se los ha visto luciendo casi todos los uniformes hasta el año 70, aproximadamente, de los que se mostraron algunos al hablar del chiripá. Se usaba suelto, tapando la bota hasta el pie o metido dentro de la bota. También se utilizaron de un ancho muy exagerado, como lo muestran las fotografías del libro de reseñas El Gaucho , que recopiló José M. Paladino Gómez.

One of the pieces of clothing the gaucho wore the most, and that he made by himself, was the “bota de potro” [boot of foal]. There were alpargatas [espadrilles], but it was necessary to have money to acquire them and they were short-lived, for that reason, it was necessary to replace them. Soon our gaucho came up with an idea to cover his feet without spending any money, because the material he needed was the most abundant in the fields he wandered at his free will: horses.

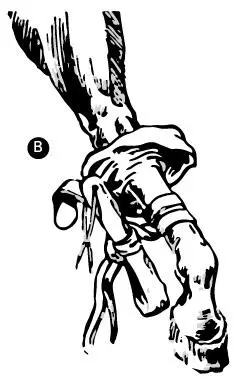

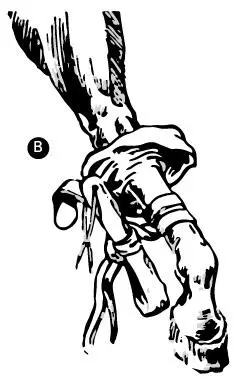

From the leg of a foal or a cow —as a last resort—, he made his boots. He cut the hide round at the height of the knee pit and the knot (A), and he detached it pulling. In order to detach the part corresponding to the shin, he put in the middle a rope folded in two with the whip or another similar object, and “making a tourniquet” or “dando garrote”, as Spaniard people said, because it was similar to the torture applied in Spain for the executions; in sum, spinning that girdle, the gaucho managed to detach the hide. The drawing marked with the letter (B) is quite clear. Once he got to remove the hide, he turned it so the inside was left out; he put a board inside and he proceeded to take out the flesh (C). He was careful to leave the back and the sides of the hock thicker, because these parts were going to be the boot’s sole. Some gauchos rubbed the hide with milk (so it acquired not only softness but a special whiteness), before it got completely dry, since rubbing them was a very important task to obtain a flexible boot, like a glove.

These boots could be hairy or sliced, depending if the hair was preserved or not. In the first case, they were very flamboyant if the animal’s leg from which the hide was detached had equal spots. There were so many horses wandering in wild freedom that the countryman could afford to have hairy boots for the winter, because they were warmer, and sliced —that is, without hair— for the summer. If they were well rubbed, the shape was obtained when they were worn. The tip (or mouth) was left open if the gaucho put the stirrup “in between the toes” (D).

There are two shapes of these “open boots” known: one only leaves the toes outside; instead the “half a foot” boot, as its name indicates, leaves almost half a foot in sight. It was rare to find a barefoot countryman, but there were some. Even women used to wear short this kind of boots. The shoe, in that time when they were forced to live far from a village, was very difficult to obtain.

Lucio V. Mansilla, in his book Viaje al país de los ranqueles , refering to the daughter of a cacique, says:

“For lack of shoes, they had put her some short botas de potro, made from cat hide”.

Since the countryman used the stirrup and, therefore, he introduced the tip of the foot there, he closed the mouth of the boot sewing it in, giving it the shape of the foot; or, otherwise, he wetted the tip and he bent it up or down and he tied it strongly at the height of the two largest toes. Once it was molded to the foot, he did a small seam. Afterwards he turned the boot out and the seam remained inside, but without causing any harm to the foot.

Figure (E) shows the tip of a boot that was sewed inside. The ways to wear the boots were diverse: they were the small luxuries of the countryman, along with a few other garments and, specially, the horse and the tack. His fantasy drove him to choose boots with similar spots in the hair. Some people wear short-cane boots; other people cut them much longer and then, when they put them, they turned the top over. They call this kind of boot “bota con delantal” [boot with apron] (F). They also used to cut fringes in thin strips, giving them an attractive shape: they called this “delantal con flecos” [apron with fringes] (G). If these last two types of boot had the hair outside, the turn or apron was white because was the sliced part.

Читать дальше