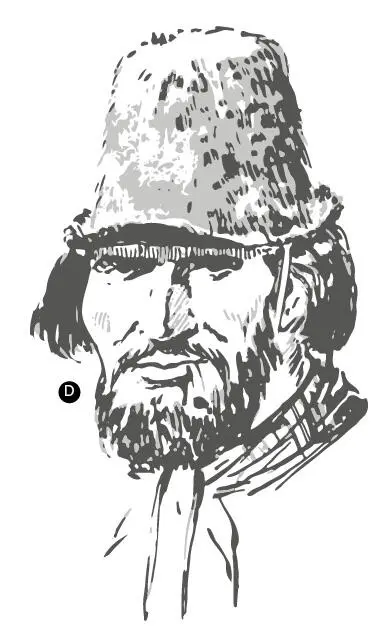

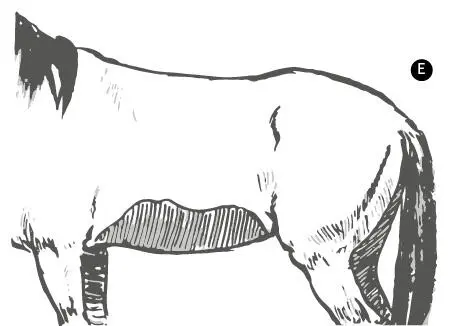

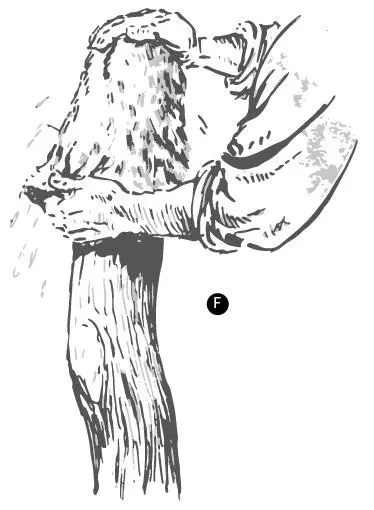

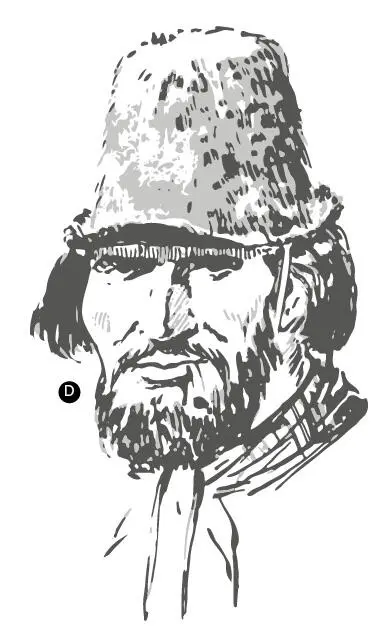

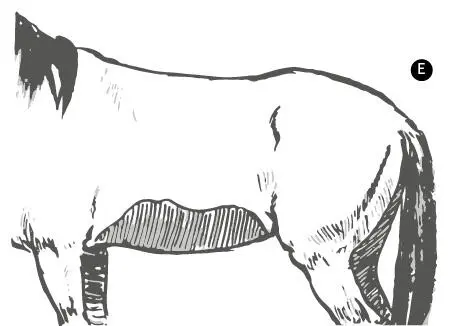

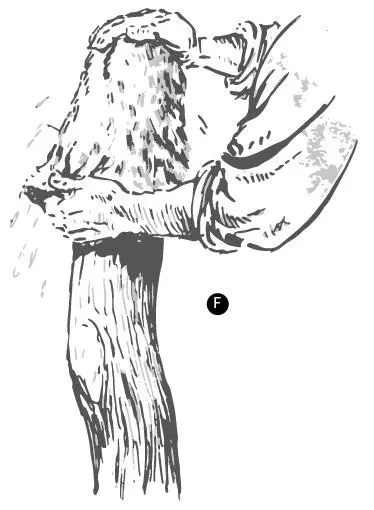

Un sombrero muy común, usado por el paisano de tierra adentro, fue el llamado “panza de burro” (D); como su nombre da a entender, se confeccionaba con el cuero sacado de la panza de un burro (E). El paisano, al hacerlo, conservaba el pelo del cuero. Primero lo sometía a una larga inmersión a fin de ablandarlo. Mojado y dejándolo hacia afuera, lo moldeaba en un poste para darle la forma que deseaba (F). Luego lo colgaba al aire libre y así se endurecía. El arreglo se completaba con tiras de cuero que anudaba bajo el mentón o en la nuca.

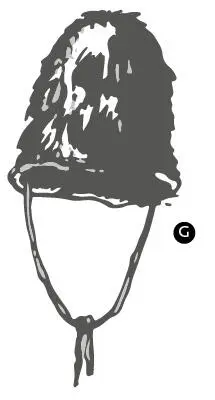

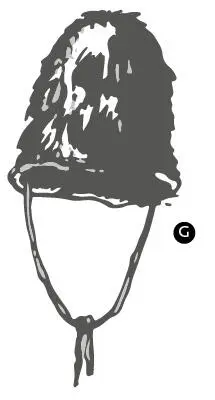

La figura (G) muestra cómo era el sombrero concluido. No hay mucho más para decir salvo que semejaba una campana. Suponemos que no debía ser muy fresco ni muy liviano.

También muy usado el pañuelo atado a la cabeza y anudado atrás en la nuca. No hay duda de que, salvo el “panza de burro”, todos los sombreros que usaron nuestros paisanos fueron importados o inspirados en el extranjero.

Al hablar de los gauchos salteños, nombramos el amplio sombrero de cuero, común en la zona norteña, cubierta de montes achaparrados y agresivas espinas, con él se defendía. El “panza de burro” no poseía alas pronunciadas, se puede decir que carecía de ellas. No las necesitaba en una zona carente de bosques naturales y plantas espinosas, porque los que lo usaban eran, por lo general, de la pampa húmeda.

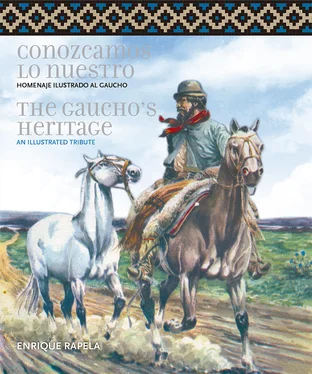

In these short reviews on everything concerning the gaucho, we will briefly talk about the hat or “cubrecabeza” [headcover], because there would be no other way to call what they wore over it.

They wore hats with different shapes and made of several materials. Through the lithographies by Pallière and Pellegrini (known artists of the time on whom we have to rely to know details of the garments of our ancestors before Daguerre’s documentation), we see that the top hat (A) was widely used. People say that the reason was a shipment of these pieces of clothing brought by an English ship that, by a very common accident in this coast, was forced to unload its cargo. The top hats went then to the shops’ shelves both in the cities and the countryside.

Our countrymen have no problem in covering their heads with them. There is a well-known painting where Justo José de Urquiza appears covered with his poncho and wearing this famous top hat with his military uniform. The straw hats, widely used at all times, had different shapes and sizes. Figure (B) represents a countryman with a conical straw hat. Other flat shaped models with a narrow brim had a wide diffusion in the early years of the 19th century. Usually, they were known as “jipi-japa”.

In Rosas’ time, the “gorro de manga” [a hat with a long bent top] went into fashion, because it was worn by regular troops. They were known under different shapes. At early 19th century there was an army corps —the Infantry of Retiro— that wore a blue gorro de manga with a particular shape, known as “de mitra” [miter]. We know that thanks to a watercolor of the time, belonging to Justo Mateo who gave it as a present to the notary Victoriano José Cabral, who, in turn, gave it to Enrique Udaondo, who published it in his famous book on military uniforms. Supposedly, the man in the painting is colonel Valerio Sánchez, who occupied the colonial era barracks that accommodated the first squadrons of the Regiment of Horse Grenadiers.

One of the most common shapes was the one that appears in figure (C).

In the pictures illustrating the chiripá , we can see soldiers with different gorros de manga . So, we have the long and white hat that falls limp worn by a soldier from the Cavalry of Santos Lugares. In the 1839 carabineer, we can see the tall and rigid hat called “gorro de mitra”, because of its similarity to the episcopal miter. But they were not only worn by Rosas’ men, Urquiza´s infantry and cavalry, and the artillerymen of the Confederation wore them too.

It was discovered too that the 1865 National Cavalry Guard wore a blue hat with a blue long top, a ring and a red tassel. This reminds us the Phrygian hat that the French wore during the Revolution and that marks a milestone in history.

A very common hat, worn by the inland countrymen was the one called “panza de burro” [donkey´s belly] (D); as its name implies, it was made with the hide from a donkey’s belly (E). When the countryman made it, he preserved the hair in the skin. First, he subjected the hide to a long immersion in order to soften it. Wet and on the outside, he molded it in a post to give it the shape he wanted (F). Afterwards, he hung it outdoors and it hardened. The arrangement was completed with leather straps that knotted down the chin or at the nape.

Figure (G) shows how the finished hat was. There is not much more to say, except that it looked like a bell. We suppose that it should not be a very cool or very light hat.

A neckerchief tied to the head and knotted back at the nape was also very common. There is no doubt that, except for the “panza de burro”, all the hats our countrymen wore were imported or inspired abroad.

When we talked about the gauchos from Salta, we mentioned the wide leather hat —very common in the Northern area, covered by squad mounts and aggressive spine—, because it served him as a defense. The “panza de burro” didn’t have pronounced brims, we could say that it lacked them. It did not need them in an area that did not have natural bush lands and thorny plants, because it was worn mainly by the countrymen of the Humid Pampas.

Una de las prendas que más usó el gaucho, y que él mismo se confeccionaba, fue la bota de potro. Las alpargatas existían, pero era menester tener dinero para adquirirlas y duraban poco, por lo que era necesario reponerlas. Nuestro gaucho pronto ideó cómo calzarse sin gasto, ya que el material que necesitaba era lo que entonces más abundaba en los campos que recorría a su libre albedrío: caballos.

De la pata de un potro o potrillo o vaca, en última instancia, se confeccionó sus botas. Cortaba en redondo el cuero a la altura de la corva y el nudo (A), y lo despegaba tirando. Para despegar la parte que corresponde a la canilla le colocaba en medio una soga de a dos, con el rebenque u otro objeto similar, “haciendo torniquete” o “dando garrote”, como decían, al ser igual al suplicio que aplicaban en España para los ajusticiamientos; haciendo girar esa ceñidura, se conseguía despegar el cuero. El dibujo señalado con la letra (B) es bastante claro. Sacado el cuero, lo daban vuelta y quedaba el interior hacia afuera; metían una tabla adentro y procedían al descarne (C). Tenían la precaución de dejar más gruesa la parte de atrás y los costados del garrón, destinados a servir de suela. Algunos comenzaban a sobarlas en leche (porque adquieren, además de blandura, una blancura especial), antes que se secara del todo, pues sobarlas es una tarea muy importante para conseguir una bota flexible como un guante,

Читать дальше