OECD (2020a). “Distributional risks associated with non-standard work.” Policy note 12 June 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2020b). “Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2020c). “Job retention schemes during the COVID-19 lockdown and beyond.” Paris: OECD.

S&P (2020a). “Bank Regulatory Buffers Face Their First Usability Test.” June.

S&P (2020b). “The $2 Trillion Question: What’s On The Horizon For Bank Credit Losses?”

Sapir, A. (2020). “Why has COVID-19 hit different European Union economies so differently?” Policy Contribution 2020/18, Bruegel.

Shapiro, A.H. (2020). “Monitoring the Inflationary Effects of COVID-19.” FRSBF Economic Letter, 2020-24, August.

UNCTAD (2020a). “Key Statistics and Trends in International Trade 2019: International Trade Slump.” Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD (2020b). “World Investment Report 2020: International Production Beyond the Pandemic. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

Chapter 2

Gross fixed capital formation

Investment in the European Union fell precipitously at the onset of the coronavirus outbreak.This decline followed a slowdown in investment that had gradually set in during 2019 and was exacerbated by government restrictions on movement and business activity, especially in the second quarter of 2020.

Uncertainty and a sharply deteriorating economy, however, are the main reasons for the extraordinary decline in investment.While activity partially recovered in the third quarter, uncertainty is likely to continue to dampen investment in the near term, especially as new restrictions are introduced to contain the second coronavirus wave in the fourth quarter of 2020.

Elevated uncertainty, along with deteriorating firm finances, are likely to further impede corporate investment.The cash flows of non-financial corporates have retreated well into negative territory, causing these firms to draw down their cash balances, which might eventually eat into their net worth. This weakened position damages firms’ ability to finance investment, internally and externally. Investment weakness is likely to persist even as economic conditions gradually improve.

The coronavirus outbreak is likely to prompt increased digitalisation and, in the medium term, to cause shifts in supply chains and product portfolios.Many of the companies bearing the brunt of the ongoing crisis see a permanent reduction in employment as another longer-term consequence. Policymakers should take action to ease the reallocation of labour to avoid large increases in structural unemployment.

Government investment in 2020 may be another victim of the pandemic.Even though policy support has been strong, there are signs that government investment levels might decrease across EU Member States. The decline in government investment must be halted and reversed from 2021 onwards. Redirecting investment from current to capital expenditure seems to be the sustainable option. It can be further supported by debt issuance for countries with sound fiscal positions.

The initial impact of the coronavirus pandemic on investment in the European Union has surpassed the effects of the global financial crisis. In just two quarters, investment declined to the same extent as in the first year of the recession in 2008-2009. While there is no financial crisis to worry about yet, there are signs that investment may take a long time to recover. The purpose of this chapter is to trace the impact of the pandemic on investment and provide an analysis of the main drivers. The first section outlines the general investment trends in the European Union. Using the latest wave of the EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS), the second section explores the developments in corporate investment in 2019-2020 and expectations for 2021. The third section provides an overview of infrastructure investment through 2019 and information about infrastructure projects in the first half of 2020. The fourth section takes a closer look at government investment in the European Union in 2019, as well as the plans for 2020-2021. The last section draws conclusions about the implications for policy.

Aggregate investment dynamics

Investment growth continued until the end of 2019, but the pace slowed

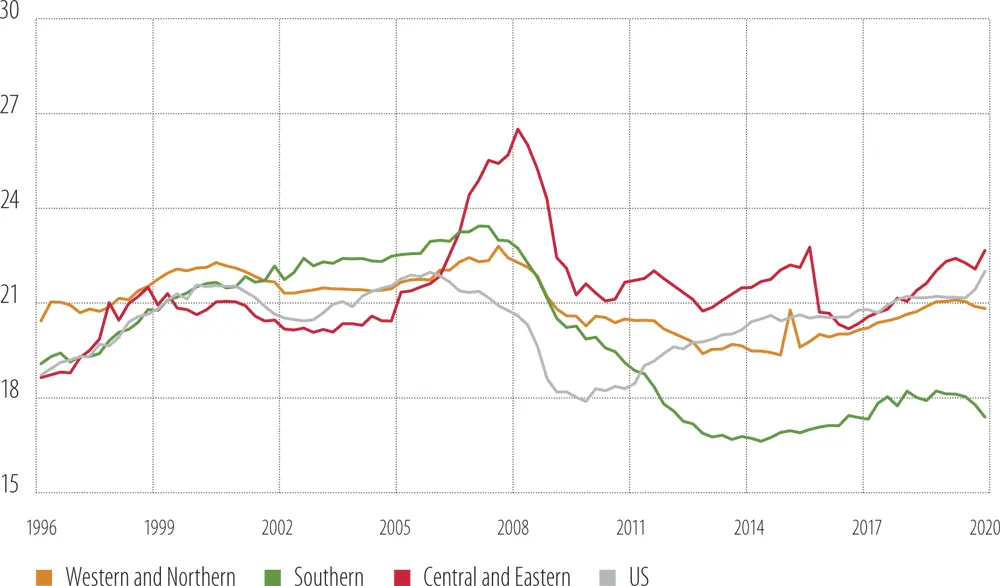

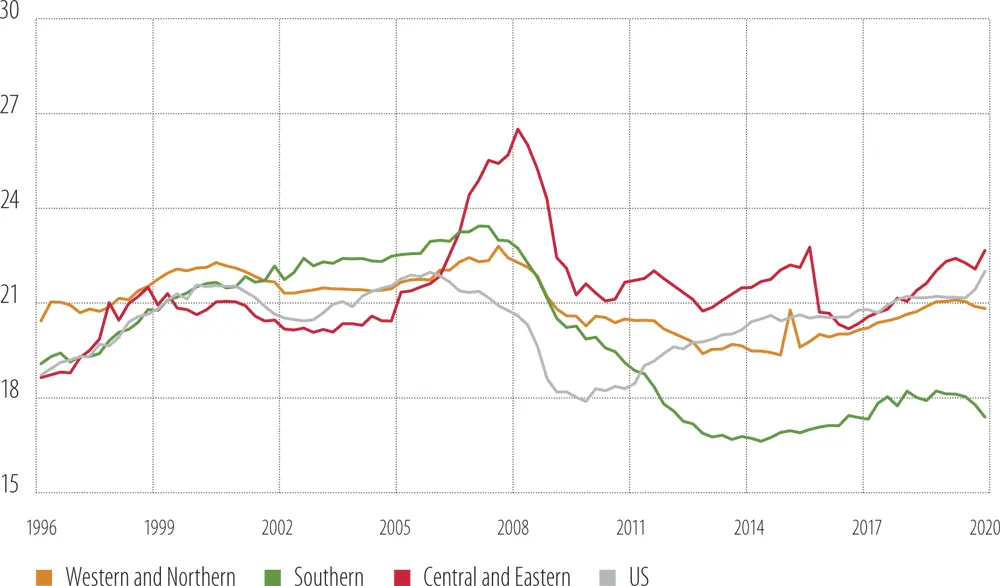

Aggregate investment rates continued to rise throughout 2019 in most EU members as investment growth outpaced growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) (Figure 1).[1, 2] The investment rate in the European Union rose above its long-term average at the end of 2019. This rise was also seen in Western and Northern Europe and in Central and Eastern Europe. The aggregate investment rate in Southern Europe, however, was 1.5 percentage points below the average of the past 25 years.

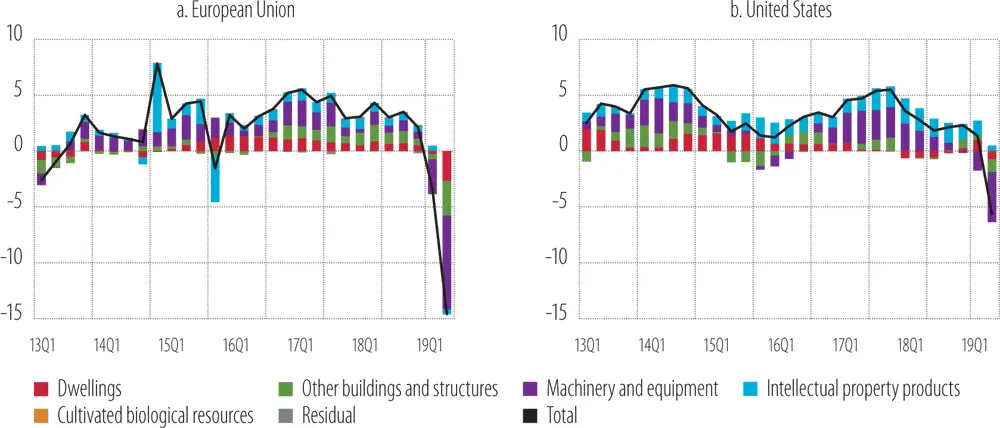

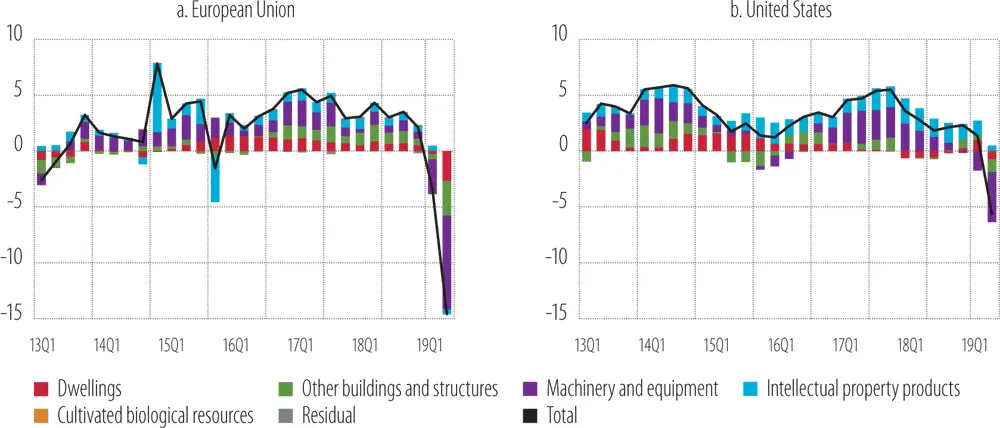

In 2019, aggregate investment in the European Union grew about 3% relative to 2018.Half of this pace of growth resulted from higher investment in buildings and structures, including dwellings ( Figure 2a). Investment in other buildings and structures, which includes infrastructure investment (discussed separately in this chapter), expanded at faster rates in Central and Eastern Europe. The investment in buildings and structures was supported by higher government capital expenditure and investment grants from the European Structural and Investment Funds ( Figure 3c). Austria, France, Germany and Portugal also saw significant investment increases in buildings and structures.

These positive developments notwithstanding, aggregate investment growth slowed down in the European Union in the second half of 2019 (Figure 2a).The slowdown was due to weakening international trade amid intensifying disputes between the United States and its main trading partners (EIB, 2019). In 2019 and early 2020, before the coronavirus pandemic drew all the attention of analysts and commentators, European economic discourse focused mostly on the weakening of the German economy as a result of falling exports.

Figure 1

Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) in the European Union and the United States(% of real GDP)

Source: Eurostat, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) national accounts and EIB staff calculations.

Note: Real investment and GDP are in euro 2015 chain-linked volumes and US dollar 2014 chain-linked volumes for the European Union and the United States, respectively. The aggregate for Western and Northern Europe does not include Ireland, due to the high volatility of Irish data that obscures group-wide developments.

Figure 2

Real GFCF and contribution by asset type(% change from a year earlier)

Source: Eurostat and OECD national accounts; EIB staff calculations.

Note: Panel a shows data for the European Union without Ireland, due to high volatility of Irish investment data that obscures EU-wide developments.

Part of the slowdown came from investment in machinery and equipment and in buildings and structures, including dwellings.Investment ran out of steam first in Southern Europe in early 2019 ( Figure 3b), mostly due to a pronounced slowdown in Italy. By the third quarter of 2019, the phenomenon had spread to Western and Northern Europe, as investment growth waned in Austria, the Nordic countries and Germany ( Figure 3a).

Читать дальше