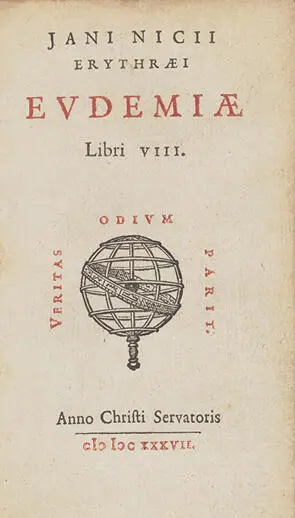

Fig. 3:

Fig. 3:

Iani Nicii Erythraei Eudemiae libri VIII . [Leiden]: [Bonaventure and Abraham ElzevierElzevier, Abraham], [1637]. Image courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

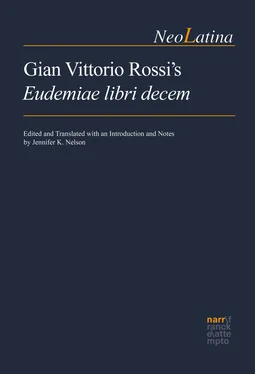

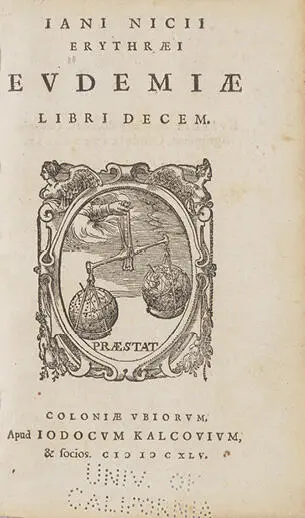

Fig. 4:

Fig. 4:

Iani Nicii Erythraei Eudemiae libri decem. Coloniae Ubiorum [i.e., Amsterdam]: Apud Iodocum Kalcovium [i.e., Joan BlaeuBlaeu, Joan] [1645]. Image courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Unpublished or Lost Works

RossiRossi, Gian Vittorio wrote a number of works that are now lost. Among his sacred dramatic works was a play titled Tobia , which, according to Leone AllacciAllacci, Leone, was published in 1629 in Viterbo.1 Rossi’s unpublished sacred plays include Esau et Iacob , Christi Domini praesepis , Filius profusus ac perditus , and Susanna . His play Magdalena flens ad sepulchrum Christi , set to music by the composer Virgilio MazzocchiMazzocchi, Virgilio, was performed multiple times, including in a private performance before cardinals Francesco BarberiniBarberini, Francesco, Ippolito Aldobrandini, Roberto UbaldiniUbaldini, Roberto, and the Polish ambassador to Rome,2 but the text has not survived. Another musical performance consisted of a sacred play about Ignatius Loyola set to music by the composer Loreto VittoriVittori, Loreto (who appears as a character in Book Ten).3 Other lost short works are Vita Iuvenalis Ancinae Saluciarum Episcopi , Vita Sancti Isidori , Vita B[eati] Stanislae Kostka , Canonis missae interpretatio , De officio ac dignitate sacerdotis , Totius missae sacrificii explicatio , and Confessiones propriae , modeled after St. Augustine’s Confessions .4

Keys to Accompany Eudemia

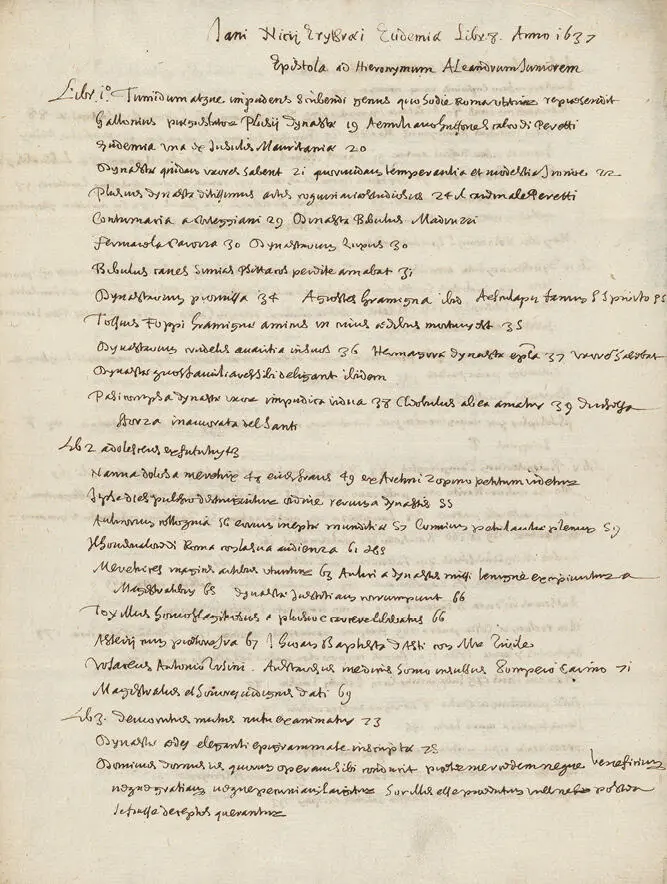

I rely primarily on six sources to identify, to the extent possible, the real names behind the pseudonyms in Eudemia . Two keys to the work have been published: Christian GryphiusGryphius, Christian’s Apparatus sive dissertatio isagogica de scriptoribus historiam seculi XVII illustrantibus (1710: 490–5) and Fernand DrujonDrujon, Fernand’s Les livres à clef (1888: 1052–7).1 Other sources for identifications are Luigi GerboniGerboni, Luigi’s Un umanista nel Seicento (1899: 131–3) and Luisella GiachinoGiachino, Luisella’s “ Cicero Cicero, Marcus Tullius libertinus ” (2002: 185–215). Jozef IJsewijnIJsewijn identified a number of names in his notes that accompany the 1998 online version of Eudemia housed on the University of Kentucky’s website.2

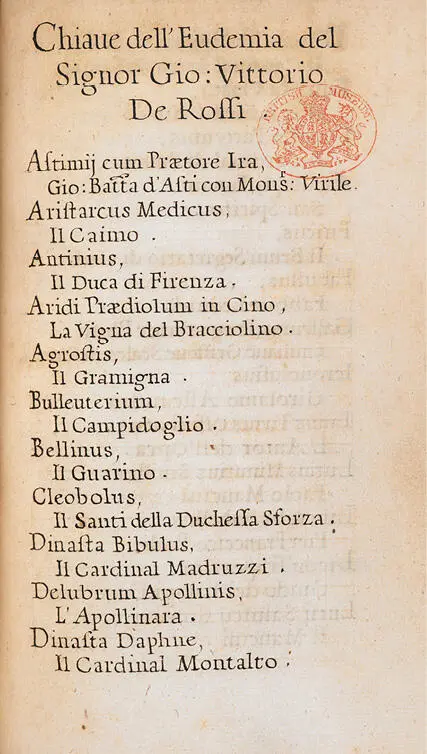

In addition, I consulted two manuscript keys. “Clavis et index in Eudemiam ,” which I identified in Harvard University’s Houghton Library archives, is in Gabriel NaudéNaudé, Gabriel’s hand and accompanies the 1637 Eudemiae libri VIII ; “Chiave dell’ Eudemia del Signor Gio. Vittorio De RossiRossi, Gian Vittorio” is sewn into a British Library copy of Eudemiae libri decem .3 Another key was apparently composed by Jean-Jacques BouchardBouchard, Jean-Jacques, which Rossi’s contemporary Cassiano Dal PozzoDal Pozzo, Cassiano mentions in his Memoriale romano ,4 while a fourth was to be drafted by the Italian author Angelico AprosioAprosio, Angelico.5 Unfortunately, I have found no trace of either of these two last keys.

Where discrepancies occur among the existing keys and scholarly sources, I took the further step of consulting RossiRossi, Gian Vittorio’s Pinacotheca , since a significant number of the characters in Eudemia were also the subjects of his biographies. Identifications not gleaned from any of the existing keys and sources, and unique to this edition, are based on the similarities of the pseudonyms to names of real people, as well as on my own research. Examples of these are Giovanni Battista TamantiniTamantini, Giovanni Battista for ThaumantinusThaumantinus (Giovanni Battista Tamantini), Margherita CostaCosta, Margherita for PleuraPleura (Margherita Costa) (who also appears in Pinacotheca ), and Francesco BarberiniBarberini, Francesco for the animal-loving Dynast BibulusBibulus (Francesco Barberini?). In addition, I identify a number of physical locations in Rome that do not appear in any of the sources, such as the Villa Peretti-Montalto for the Placidiani Gardens, the Villa Farnesina for a sumptuous villa on the banks of the river, and the Villa Borghese for the site of a May Day picnic (these latter two in Book Ten).

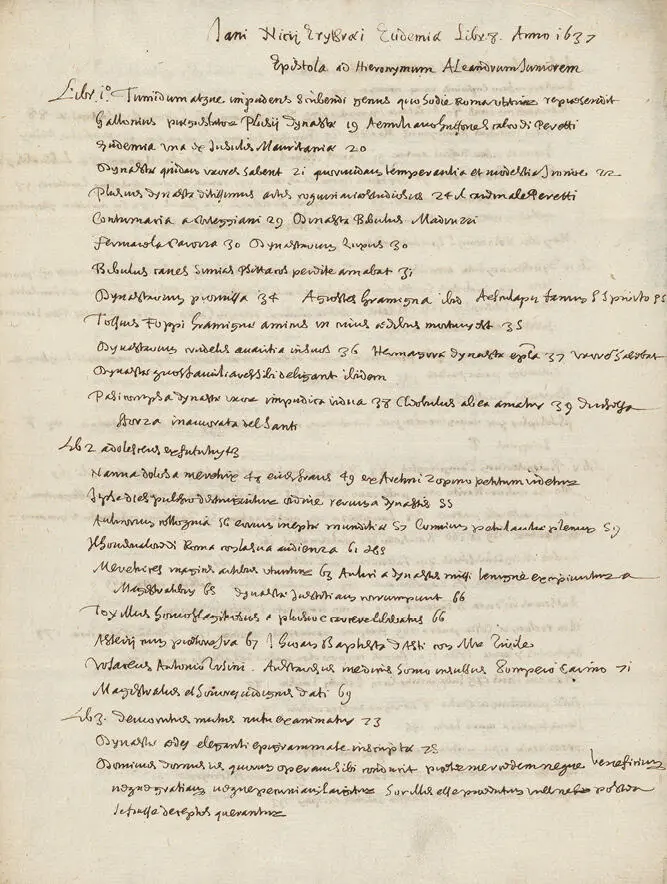

Fig. 5:

Fig. 5:

“Clavis et index in Eudemiam .” MS Lat 306.1, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

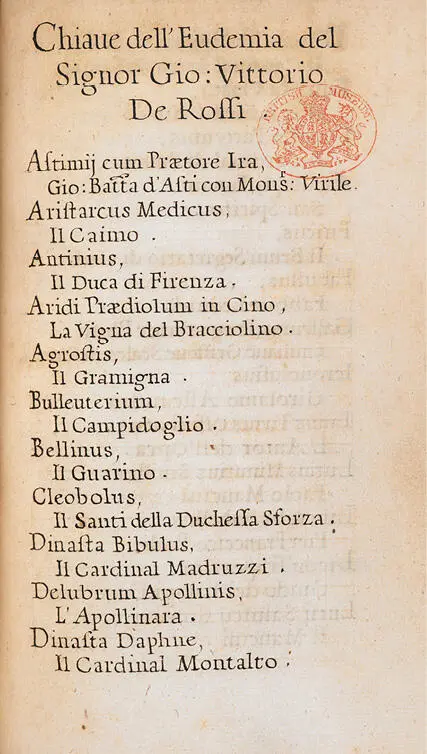

Fig. 6:

Fig. 6:

“Chiave dell’ Eudemia del Signor Gio.Vittorio de RossiRossi, Gian Vittorio” sewn into Iani Nicii Erythraei Eudemiae libri decem (1645) © British Library Board, 12410.aa.16.

Literary Models for Eudemia

Ancient Models

In a letter to Carlo MazzeiMazzei, Carlo, written a year after the publication of the second edition of Eudemia in ten books, RossiRossi, Gian Vittorio addressed his correspondent’s apparently negative reaction to his work:

Doubtless some aspects of my Eudemia have recently caused you offense because, in recounting the vices of several people, I have more than once exceeded the bounds of moderation. But keep in mind the works of HoraceHorace, JuvenalJuvenal, and others, who did the very same thing with the utmost freedom of speech and sentiment. Consider in particular PetroniusPetronius Arbiter Arbiter, whom I have attempted to imitate. As you can see, he rubbed the city with much salt and vinegar, just as Horace says about LuciliusLucilius Gaius. Finally, do not forget that my work is a satire, which I consider extremely difficult not to write in the face of mankind’s corrupt and irredeemable morals.1

Implied in this passage is that, because of its criticism of contemporary mores, Eudemia was not universally well received.

In his own defense, RossiRossi, Gian Vittorio inserts himself into a long and venerable line of ancient Roman satirists, whose legendary libertas (freedom of speech), he argues, enabled them to criticize their own societies. Rossi names PetroniusPetronius Arbiter Arbiter as his most immediate model, whose Satyricon , with its episodic tale and mix of prose and verse, is the closest ancient work to Eudemia in terms of genre. As additional models he cites the verse satirists HoraceHorace, JuvenalJuvenal, and LuciliusLucilius Gaius, and he closes this passage with a phrase inspired by a line in Juvenal’s first satire, “difficile est saturam non scribere” (“it is difficult not to write satire”).2

RossiRossi, Gian Vittorio invokes these ancient satirists as cover for any offense he may have caused. So what if he went a little too far in poking fun at his contemporaries (“non semel modestiae fines praeterierim”)? Is that really any different from what the greatest satiric poets from Rome’s illustrious past had done? Rossi’s explanation of his satiric pedigree, however, merits examination. First of all, Rossi is inserting himself into two distinct satiric traditions: prosimetric Menippean satire in the Petronian vein,3 and the verse satire of LuciliusLucilius Gaius, HoraceHorace, and JuvenalJuvenal. Second, and more important, he is pinning his defense on the question of libertas , which, out of all of the ancient predecessors he mentions, was only enjoyed by Lucilius.

Читать дальше

Fig. 3:

Fig. 3: Fig. 4:

Fig. 4: Fig. 5:

Fig. 5: Fig. 6:

Fig. 6: