In the mid-term, demographics will start to play against right-wing populism, while the left will thrive on a generation of young people who are being increasingly neglected and expect more from the state. What happened in Latin America in the 2000s with the rise of populist left-wing governments (often disguised as progressives) could repeat itself in developed countries if liberal governments do not renew their commitment to the middle class and take the necessary measures to rebuild the meritocracy.

Pandemials are the young people born in the years following the fall of the Berlin Wall and entering the job market during the Covid-19 crisis. They are a generation with strong ethical values and ecological awareness owing to having been born knowing that the planet is at risk. They will find societies marked by inequality, the end of meritocracy, solitude, digital automation, the depletion of natural resources, and a variety of environmental crises that will affect life on the planet. In addition to not enjoying the same economic prosperity as their parents –which, for example, allowed them to access a university education or lead more comfortable lives– this generation will face fewer job opportunities, discouraging prospects, and a growing need to radicalize their complaints. As a result, pandemials will expect much more from governments, and when their neglect is not addressed, they will rebel. They will go after the technocratic elites and the foundations of the capitalist system. Liberal governments’ lack of answers to these problems will push them to rekindle old models and left-wing utopias.

Pandemials are carrying out a rebellion in response to the lack of interlocutors or policies to resolve their problems. Their revolution is against the technocracy, the powerful group that has handled public policy since World War II. To them, the technocracy is represented by the political parties who have been in office for the last few decades, bankers, lobbyists, and institutions such as the European Commission or the International Monetary Fund (IMF). They are also rebelling against right-wing populism, rejecting authoritarianism, discrimination, and conservative values on social matters. This new rise in populism, conservatism, and authoritarianism has taken place in a large portion of the world: the United States, parts of Europe, Latin America, and East Asia.

Faced with this situation, liberalism radiates stubbornness and inspires disenchantment: it tries to solve the problems of today using the recipes of the past on a larger scale. The ideology that used to look to the future now turns inward, displaying its inability to renovate its ideas and come out from under the dominion of a self-serving technocracy. This closed-minded even elitist approach does not reflect the essence of liberalism, i.e., the meritocracy and openness that characterizes it. Without a renewal of ideas and a greater openness, the spread of populism will be hard to stop.

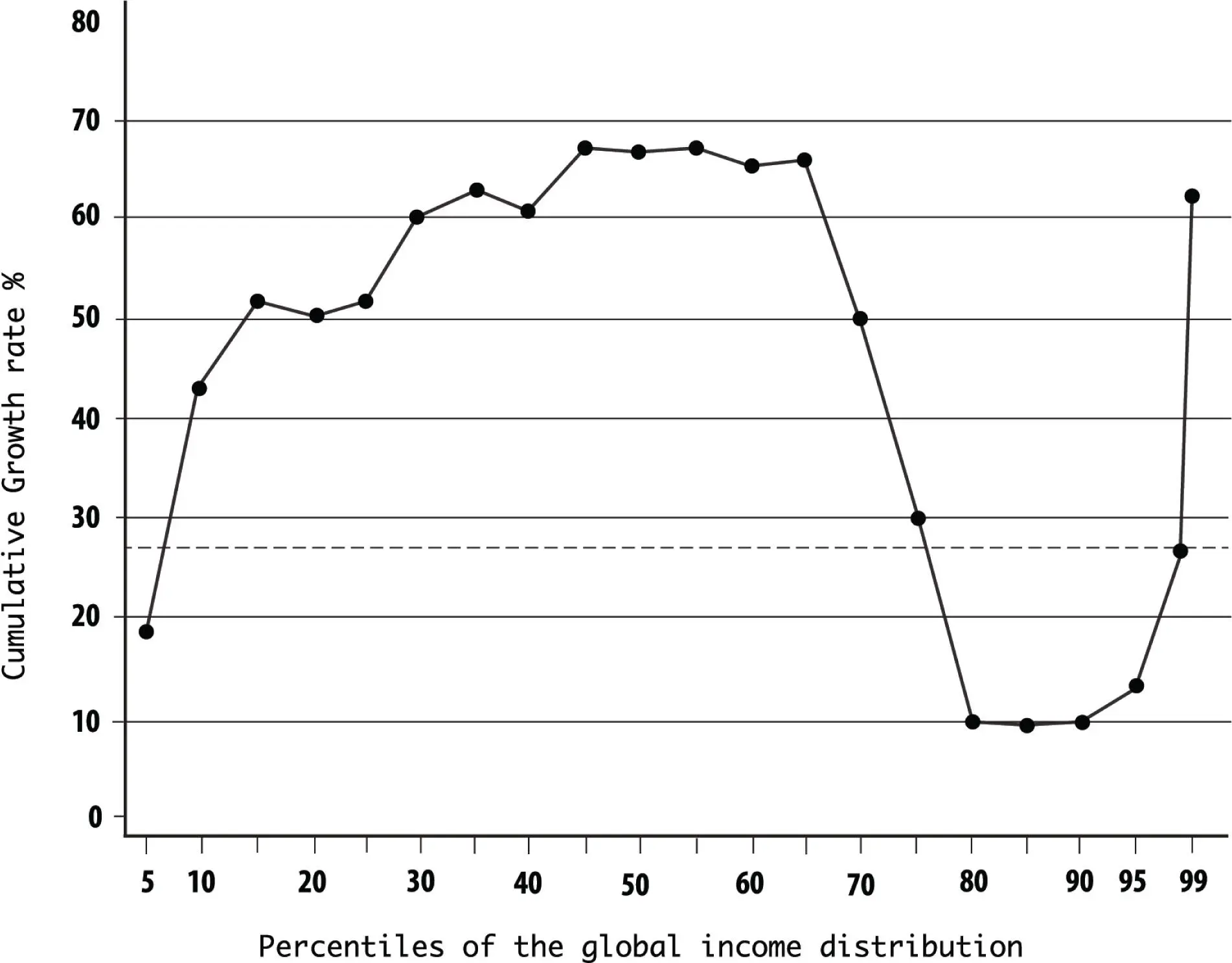

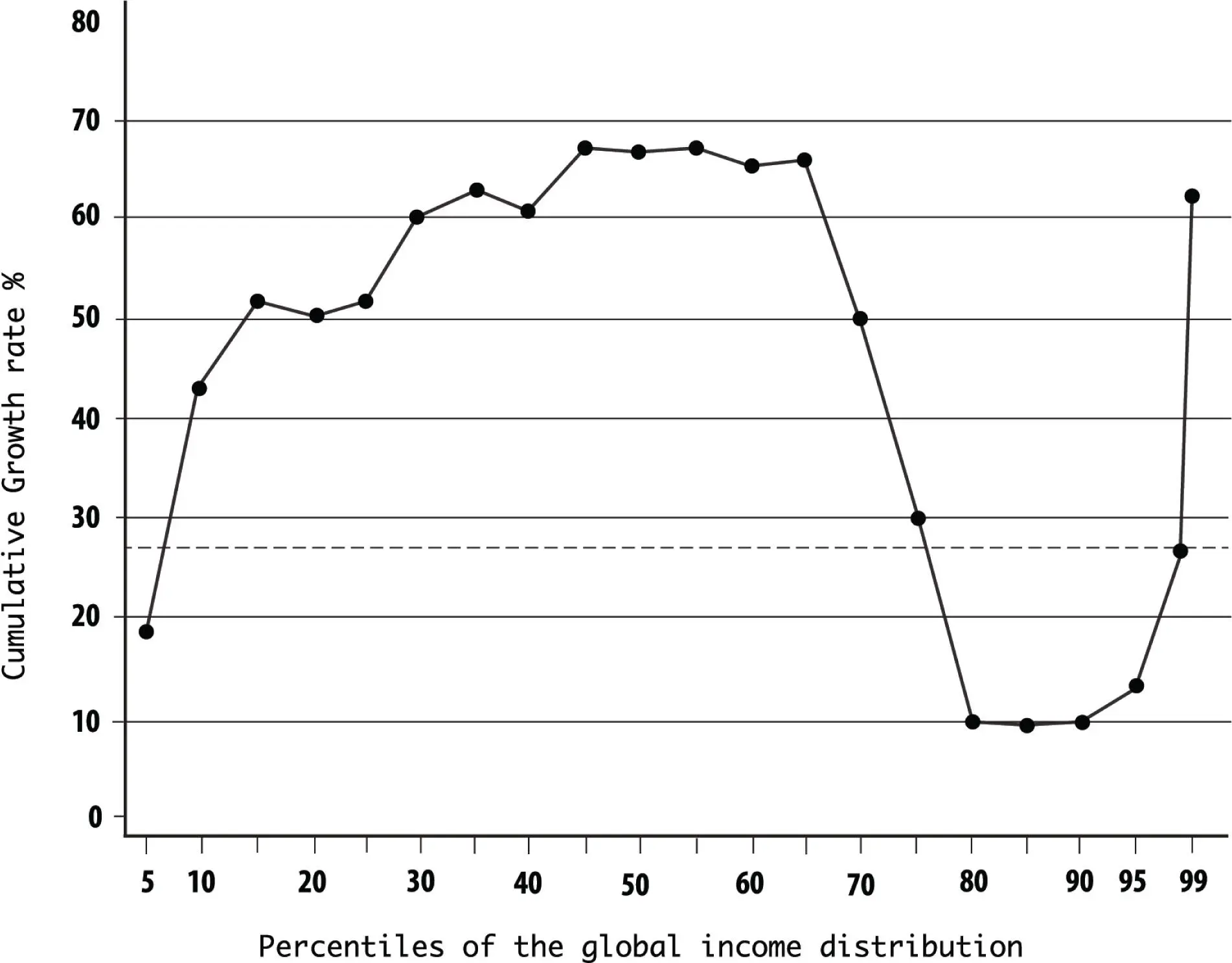

GLOBAL GROWTH INCIDENCE CURVE (2)

New, non-statist approaches will be needed to recover meritocracy and provide solutions to the complaints of young people, which range from lower sales and income taxes to more efficient education models such as charter schools, from a serious stance against climate change to a monetary policy that contributes to human progress.

The elephant-shaped graphic reflects the dissatisfaction of the middle class in many developed countries. In it, you can see the global income growth per income quintile between 1988 and 2008. The middle section pertains to emerging countries such as China, whose middle-class incomes grew a lot more. In the 80-95 quintile, the lower rate of growth reflects the middle classes in developed countries. The trunk relates to the rich whose income has grown significantly.

The paradox of liberalism is that in many of the countries where it was implemented, its middle classes sunk into the precariat, while in the rest of the world, the free market and globalization upheld by its ideology lifted millions of people out of poverty. From a global standpoint, the world has never been better off and the percentage of people in the middle class is at a record high thanks to the economic growth of China and other emerging countries. However, this process is losing steam. China’s initial progress, which relied on copying technology and exporting to the rest of the world, is starting to face the limitations caused by a lack of freedom and innovation.

The pandemic struck in this context, which is like an iceberg of problems that we could only see the tip of at first but now it has fully emerged. Following events of this magnitude, two things happen: social and economic processes accelerate and demands for change intensify.

THE HUMAN CYCLES

“The world will never be the same.” “This is the end of liberalism.” “We will see a new world order.” “China will dominate the world.” “Covid-19 was sent by God as punishment for the damage we are doing to our planet.” “The ‘New Normal’ is here to stay.” I read these proclamations and many others like them about the pandemic during the first several months of the global lockdown in 2020. In truth, the world will not just change because of Covid-19, there will be an acceleration of many processes that began over the last few decades. Changes we expected to see in five or ten years will happen in just two or three.

Premiered in May 2019, the UK television series Years and Years , co-produced by the BBC and HBO, depicts what could happen if the world were to continue down the current path. The series follows the lives of the Lyons family between the years 2019 and 2034 as Britain is rocked by unstable political, economic and technological advances.

During this period, the UK and world political realities become increasingly unstable and give the viewer a glimpse of a possible future. In the show, the impact of technological innovation on the economy and society, inequality, and the expansion of populism fill the characters’ lives with misery. At the end of each episode, the viewer is left with a feeling of anguish and emptiness, well-aware that even though such a future is unlikely, it remains a possibility.

Since its beginning, humanity has coexisted with different forces: inequality, mother nature, technology, and the human spirit ; each one with its own cycle; all of them interconnected.

Many of the powerful changes that are currently driving the Uprising of the Pandemials began in the 1980s. The cycle of increased equality that began with the welfare state following World War II came to an end with the fall of the Berlin Wall, giving way to a cycle of growing inequality. Technological change combined with the rise in the price of the meritocracy basket (housing, education, and health) increased inequality around the world. Throughout the decade, the threats to the cycle of mother nature –the mounting evidence of the threat of climate change and the depletion of natural resources– became irrefutable. In the 1980s, toward the end of the Cold War, the governments of the world began to invest increasingly less in science and technology. At the same time, the crisis of the human spirit caused by the shattering of century-old structures and institutions was aggravated, while the new models had still not been consolidated, all of which were amplified by new technologies that deepened the crisis of loneliness.

The next important period was the global crisis of 2007–2008 when it became clear that the four cycles were headed toward an implosion, an ending that would give way to new cycles. It was during this crisis that the inequality and injustices of the system rose to the surface, along with the strong support of many voters for populist governments.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)