Selim Özdoğan was born in Germany in 1971 and has been publishing his prose since 1995. He has won numerous prizes and grants and taught creative writing at the University of Michigan.

Ayça Türkoğlu is a writer and literary translator based in North London. Her translation interests include the literature of the Turkish diaspora in Germany and minority literatures in Turkey.

Katy Derbyshire translates contemporary German writers including Olga Grjasnowa, Sharon Dodua Otoo and Heike Geissler. She teaches literary translation and also heads the V&Q Books imprint.

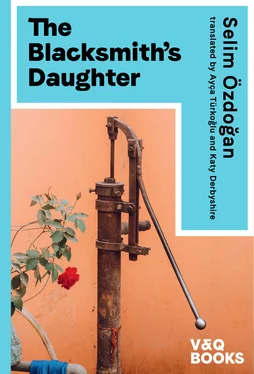

The Blacksmith’s Daughter

Selim Özdoğan

Translated from the German by Ayça Türkoğlu and Katy Derbyshire

V&Q Books, Berlin 2021

An imprint of Verlag Voland & Quist GmbH

First published in the German language as Selim Özdoğan, Die Tochter des Schmieds .

© Aufbau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin 2005

All rights reserved

Translation copyright © Ayça Türkoğlu and Katy Derbyshire

Editing: Florian Duijsens

Copy editing: Angela Hirons

Cover photo © Arun Sharma

Cover design: Pingundpong*Gestaltungsbüro

Typesetting: Fred Uhde

ISBN: 978-3-86391-294-9

eISBN 978-3-86391-309-0

www.vq-books.eu

Über den Autor Selim Özdoğan was born in Germany in 1971 and has been publishing his prose since 1995. He has won numerous prizes and grants and taught creative writing at the University of Michigan. Ayça Türkoğlu is a writer and literary translator based in North London. Her translation interests include the literature of the Turkish diaspora in Germany and minority literatures in Turkey. Katy Derbyshire translates contemporary German writers including Olga Grjasnowa, Sharon Dodua Otoo and Heike Geissler. She teaches literary translation and also heads the V&Q Books imprint.

Kapitel I

Kapitel II

Kapitel III

Acknowledgements

The Co-Translators in Conversation

It is doubtful, of course, that things happened that way, but what we don’t know, we don’t know .

Mikhail Bulgakov, translated by Pevear & Volokhonsky

Your life has a limit, but knowledge has none. If you use what is limited to pursue what has no limit, you will be in danger .

Zhuang Zhou, translated by Watson, Palmer & Breuilly

‘Don’t make my husband a murderer, I told him. Stop the car, don’t make my husband a murderer. Stop the car and let me out, and then piss off as fast as you can.’

Timur exhales and turns his head away so Fatma can’t see him tearing up. He’s still struggling for breath. He’s grateful, so grateful that fate has chosen this woman for him. She must have been written in his book of life on the very day he was born. He doesn’t know what’s happened to him, where all the time has gone.

Just yesterday he was a little boy in ragged trousers, scrumping pears from the neighbour’s garden with his friends. The neighbour had spotted the thieves, and they’d all jumped swiftly over the wall, pockets and shirts full of fruit. All but Timur, who’d been a little too slow, as usual. Though he could run just as fast as the others, he always missed his chance to make a bolt for it. Now he stood there, rooted to the spot, and the neighbour ran past Timur up to the wall and yelled after the escaping boys: ‘Come back! Come back, and give Timur a pear, at least. Great friends you are…’

Then he turned back to Timur and just said: ‘Run.’Timur didn’t dare go past the neighbour, so he ran all the way across the garden and jumped over the wall on the other side.

Just yesterday he’d been a little boy, not all that good at school, not all that skilled, not all that popular. Until he began to help his father the blacksmith, helped him blow the heavy bellows and fetch big buckets of water for Necmi to quench the glowing iron. Timur had built up muscles in the workshop, had proved himself hardworking and untiring. He had learned quickly, and he’d enjoyed being with his father all day long. He also enjoyed testing out his new strength. The boy who once avoided fights now let no opportunity pass to show off his superiority.

Timur had a sister, Hülya, and he could well recall the night when she was born, even though he was only five at the time. He remembered the excitement in the house, and above all his father’s determined face and his vow to open the girl’s feet, no matter what it cost him. Open , that was the word he used. Hülya’s feet pointed inwards, the big toes touching, and no one who saw them thought she’d grow out of it.

‘God means to test us,’ Timur’s mother, Zeliha, had said in a tear-choked voice, and Necmi had answered: ‘If there is a way, I will find it.’

But the doctor had said he could do nothing for the child, Necmi would have to take Hülya to Ankara if he wanted to get help for her. There were specialists there. He had to take her to Ankara and that wouldn’t come cheap.

Necmi had money, and although Zeliha was reluctant to make the journey, in the end they boarded the train and went to the big city.

‘It’s God’s will that her feet are closed,’ Zeliha had told her husband, but he’d simply ignored her.

In Ankara, the doctor explained the child was too small; they were to come back in two or three years and then he’d operate, but he couldn’t promise anything. And it would cost them.

Zeliha gave Necmi a discreet nudge. They were sitting side by side in the surgery, the baby on Zeliha’s lap. Stepping on his wife’s foot, Necmi stood up and said goodbye, cap in hand.

Outside in the dusty corridor, he said: ‘Wife, I can’t haggle with a doctor, I’m not a carpet seller, I’m a blacksmith. And he’s not a carpet seller either. I don’t care how much it’ll cost, as long as the girl is cured. I made a vow.’

‘We’ll end up going hungry just because you’ve gone and got this idea in your head. If only the Lord had given you a bit of sense to go with your stubbornness,’ she added quietly.

They slept in a cheap hotel and returned home the next day with a lorry driver from their small town. Zeliha had arranged it all. It took longer than the train and was uncomfortable too, but it was cheaper.

Her husband could almost be called well-off, but only because she managed to rein in his extravagance and earn a little extra with a few deals here and there. The evening before they left for home, Necmi had taken her to a restaurant and drunk a small bottle of rakı, and they had eaten kebab. As if bread and cheese and tomatoes and onions and a glass of water weren’t good enough. No, this man could not handle money; only she knew how to save up and multiply it.

So they squeezed into the driver’s cab. Zeliha had the baby on her lap and sat on the far side, breathing in the smoke from the two men’s roll-ups, swallowing the dust from the road right alongside them for almost ten hours. During the short stops, she made tea on a gas flame and prepared cold food while Necmi and the driver played backgammon.

Almost three years later, Necmi took the train to the capital city again, but this time Hülya was old enough not to need her mother to come along. When the blacksmith returned after four days, he carried his daughter on his back; her legs were in plaster up to the knees.

Читать дальше