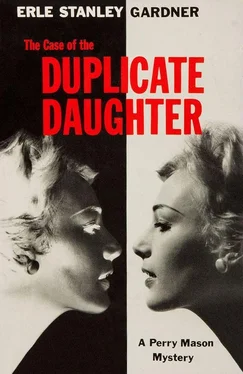

Erle Stanley Gardner

The Case of the Duplicate Daughter

The field of legal medicine is exacting, and it is a difficult field in which to achieve distinction. Relatively few men have gone to the top of the ladder.

The good medico-legal expert knows more about detective work than Sherlock Holmes, as much or more law than the average lawyer, and must be firmly grounded in all branches of medicine. In addition, he must have a quick, perceptive mind, be able to express his thoughts clearly and concisely and have such self-control that he can’t be rattled or enraged by the sneering type of cross-examination with which some attorneys try to embarrass a medical witness.

To achieve international distinction in this field is an honor indeed, and it is a distinction that has been achieved by my friend, Doctor Francis Edward Camps.

Dr. Camps is as much at home working with Scotland Yard on some puzzling matter as he is rendering services as a consultant while visiting friends in the United States. There is no room here to list his honors in England, but in the United States he is a member of the Harvard Associates in Police Science, and a Fellow in the American Academy of Forensic Sciences. He has written a most interesting book dealing with his work in the famous Christie case in Great Britain ( Medical and Scientific Investigations in the Christie Case — Medical Publications Ltd.) and that book alone shows the outstanding qualities of the man: his painstaking attention to detail, his innate shrewdness, his thorough training and, in addition to that, his ability to express himself so interestingly that this work, which is really a scientific treatise in post-mortem detection, reads as absorbingly as any mystery novel ever written.

In addition to this, he has recently, in collaboration with Sir Bentley Purchase, written a book on forensic medicine entitled Practical Forensic Medicine, a book which is destined to become a leader in the field.

Dr. Camps has visited at my ranch, and has shown himself to be a warm, human, personable individual. He can relax in the company of his friends and be so genially casual that one has a hard time associating such a warm and informal personality with the medical genius who has followed seemingly insignificant clues to bring murderers to death, criminals to justice and, on occasion, exonerate persons wrongly accused of crime.

In dedicating this book to Dr. Camps I am keenly aware that he wouldn’t want to be singled out as an individual, or given any personal publicity. He is, however, keenly interested in improving the public understanding of legal medicine and so I feel sure that he will accept this dedication as a part of my effort to make the reading public familiar with the importance of legal medicine to their daily lives, to their human rights, and to their safety.

Altogether too many murders have been diagnosed as suicides and, unfortunately, too many suicides have been held to be murder. It is difficult for the public to realize the hairline distinctions which must be made by a competent examiner.

Because the medical examiner is inherently modest, the public knows all too little about the extent to which its safety is protected by this group of men who have dedicated their lives in a most difficult field. A good expert in the field of legal medicine must first learn enough medicine to qualify himself as a medical doctor, then acquire enough experience to reach the highest income brackets if he chooses simply to practice medicine. Then he must study enough law to qualify as an expert. (In fact, many of these men do take the bar examinations and become attorneys at law.) Then he must specialize in pathology, go on to study crime detection, learn all there is to know about poisons and poisoners, and then deliberately obscure himself in the relatively low-paid field of forensic medicine so that he can be free to do good in the world in his chosen calling.

The public owes this unselfish and devoted body of men a great debt of gratitude.

And so I dedicate this book to a man who has achieved international recognition in a most difficult field—

My friend,

FRANCIS EDWARD CAMPS, M.D.

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER

Muriell Gilman, moving from the dining room into the kitchen, was careful to hold the swinging door so it wouldn’t make a noise and disturb her stepmother, Nancy Gilman, who usually slept until noon, or Nancy’s daughter, Glamis, whose hours were highly irregular.

Muriell’s father, Carter Gilman, was hungry this morning and had asked for another egg and a slab of the homemade venison sausage. The request was unusual and Muriell felt certain the order would be countermanded if she gave her father an opportunity to reconsider, so she had hesitated over actually starting to warm up the frying pan. But after it appeared her father not only definitely wanted the added food but was growing impatient at the delay, she eased through the swinging door, leaving her father frowning at the morning paper, and turned on the top right-hand burner of the electric range.

Muriell understood her father very well indeed, and smiled to herself as she recalled his recent attempt to lose weight. This added breakfast order was probably open rebellion over his low-calorie dinner of the night before.

They lived in a huge, old-fashioned, three-story house which had been modernized somewhat after the death of Muriell’s mother. Muriell had been born in this house, knew its every nook and corner and loved it.

There were times when she felt a qualm at the idea of Nancy occupying her mother’s bedroom, but that was when Nancy wasn’t physically present. There was something about Nancy, a verve, an originality, a somewhat different way of looking at things, that made her distinctive and colorful. One could never resent Nancy Gilman in the flesh.

The sausage, which had been frozen, took a little longer to cook than she had anticipated. Having delayed starting to cook it until her father had shown signs of impatience, she had then put the egg in a frying pan that was a little too hot. As soon as she saw the white begin to bubble she lifted the pan from the stove. The egg sputtered for a moment in the hot grease, then subsided.

Muriell’s father liked his eggs easy over and very definitely didn’t like a hard crust on the bottom or at the edges.

Muriell turned the stove down and cautiously returned the frying pan to the burner. She tilted the pan, basted the yolk with hot grease so as to expedite the cooking process and then skillfully turned the egg over for a few seconds before removing it from the frying pan.

Arranging the egg and the sausage on a clean plate, she gently applied her toe to the swinging door between the kitchen and dining room and gave the door a shove, catching it on the rebound with her elbow so that the jar of the return swing would be minimized.

“Well, here you are, Dad,” she said. “You—”

She broke off as she saw the empty chair, the newspaper on the floor, the filled coffee cup, the smoke spiraling upward from the cigarette balanced on the side of the ashtray.

Muriell picked up her father’s empty plate, slid the new plate with the egg and sausage into place, put a piece of toast in the electric toaster and depressed the control.

As she stood there waiting for her father to return, her eye caught an ad in the paper, an ad which offered unmistakable bargains in ready-to-wear; so Nancy stooped, picked up the paper and became engrossed in garments and prices.

When the hot toast popped up in the electric toaster, she became frowningly aware that her father hadn’t returned.

She tiptoed to the door of the downstairs bathroom, saw the door was open, and looked inside. No one was there.

Читать дальше