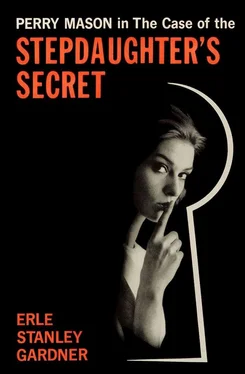

Erle Stanley Gardner

The Case of the Stepdaughter’s Secret

James Davis was an American Indian.

He was attuned to Nature in a way most modern-day city dwellers can’t understand. At times he would put on his old clothes, go down to the river, and sit on the bank for hours, just watching the swirl of the water and listening to the wind in the trees.

In this way he kept in tune with the infinite and renewed his spiritual courage. It was as if he were listening to the voice of Nature.

James Davis had been admitted to the California Bar and subsequently elected to the office of District Attorney of Siskiyou County. The citizens of the county liked and respected him.

Then, one night in 1936, two popular officers were killed while trying to arrest two men who had been in a fight earlier with two other men.

One of the complaining witnesses was killed at the time of the arrest. The other survived. He told his story to the police and then to James Davis.

The story he told Davis did not in Davis’ opinion support a murder charge. A short time later this man again told his story.

I am not concerned here with the truth of the story. I am concerned with Davis’ mental attitude and his moral courage.

Davis said the first story told by the prosecuting witness showed that the two men who had done the shooting had acted in justifiable self-defence. (The officers had taken the prosecuting witnesses with them to the camp where the defendants were in deep sleep. At the moment the officers “jumped” on the sleeping men there was evidence that one of the prosecuting witnesses had yelled, “Pour it to those sons of bitches.” The defendants, awakened from a sound sleep with these words in their ears, had come up fighting.)

However, all that is beside the point. The thing which interests me is not the evidence in the case, but the case in the mind of the District Attorney, and what he did about it.

He refused to prosecute.

In view of the public attitude this was political suicide, and he knew it, but he remained firm and faced the storm of outraged public opinion single-handed.

Newspapers published scathing editorials. The authorities speedily appointed a special prosecutor who presented the case to a jury which found the defendants guilty and sentenced them to death. (After the defendants had spent some two years in death cells, awaiting execution, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.)

The political supporters of James Davis dropped from him like autumn leaves falling from the trees.

Davis had this to say; he said it publicly: “It is the duty of a district attorney to be guided by his analysis of the truth or falsity of evidence as he finds it. His business is to seek out the truth, subject always to human error, and be guided by that truth as he sees it, wherever it may point. The attorney for the people must regard the constitutional rights of citizens with care and discretion. He must view the situation in the light of substantial justice and whoever might be killed, whatever might be the roar of the mob. If a district attorney cannot withstand the onslaught of apparent injustice, although he may stand alone in his convictions, that district attorney is not worthy of his job. He takes the oath of office to uphold the constitution of this country, of this state, and all laws made pursuant thereto, and any other stand places him in a position of betrayal of his trust.”

Shortly thereafter Davis was no longer a county official, and not too long after that he died.

Some fifteen years later it was my privilege to be one of a group who investigated the facts in that strange battle which resulted in the deaths of three men. Largely as a result of what we discovered, there was somewhat of a change in public sentiment. The defendants were released on parole.

But the thing that stays in my mind is this courageous District Attorney who stood alone, facing the roar of the mob, and watched his political career crumble away while living in a small community where from day to day he had to face the hostility of those who had once been eager to be his friends.

It was a terrible ordeal. He could have moved away, but he stayed where he was, playing his cards to the end.

He died, but he died upholding his principles. He never knew that years after his death people from the outside would examine the case and commend what he did. It would have made no difference to James Davis.

The voice of Nature in the sound of the rushing water, in the whispering of the wind in the trees, had given this man a moral strength possessed by few men. He used the temple of the outdoors as a place in which to worship his Maker and learn what it takes to be a man.

And so I dedicate this book to the memory of the onetime District Attorney of Siskiyou County, California:

James Davis

Erle Stanley Gardner

At approximately ten forty-five, Della Street nervously began looking at her wrist-watch.

Perry Mason interrupted his dictation to smile at her.

“Della, you’re nervous as a cat.”

“I can’t help it,” she said. “To think that Mr Bancroft telephoned for the earliest possible appointment — and the way his voice sounded over the telephone!”

“And you told him that he could have an eleven o’clock appointment if he could get here at that time,” Mason said.

She nodded. “He said that he’d have to stretch the speed limit to get here, but he’d make it if it was humanly possible.”

“Then,” Mason said, “Harlow Bissinger Bancroft will be here at eleven o’clock. His time is valuable. Every minute is metered, and he plans his business along those lines.”

“But what could he possibly want with an attorney who specializes in the defence of criminal cases?” Della asked. “Good heavens, the legal secretaries say that he has more corporations than a dog has fleas. He has a battery of attorneys who do nothing but handle his work. I understand there are seven lawyers alone in the tax division.”

Mason glanced at his watch. “Wait eleven minutes and you’ll find out. Somehow, I—”

The ringing of the telephone interrupted him.

Della Street picked up the telephone, said to the receptionist, “Yes, Gertie... Just a moment,” placed her hand over the mouthpiece, said to Mason, “Mr Bancroft is in the office, saying he managed to get here a little early, that he’ll wait until eleven if he can’t see you before, but that the time element is highly important.”

Mason said, “Evidently it’s more of an emergency than I thought. Bring him in, Della.”

Della Street folded her shorthand book with alacrity, jumped to her feet and hurried into the outer office. A few moments later she was back with a man in his middle fifties, a man whose close-cropped grey moustache emphasized the determination of his mouth. He had steel-grey eyes and a manner of crisp authority.

“Mr Bancroft,” Mason said, rising and extending his hand.

“Mr Mason,” Bancroft said. “Good morning — and thank you for seeing me so promptly.”

He turned and glanced at Della Street.

“Della Street, my confidential secretary,” Mason explained. “I like to have her sit in on all of my interviews and make notes.”

“This is highly confidential,” Bancroft said

“And she is highly competent and accustomed to keeping confidences inviolate,” Mason said, “She knows everything about all of my cases.”

Bancroft sat down. Suddenly, the air of decision and self-assertion vanished. The man seemed to melt down inside his clothes.

“Mr Mason,” he said, “I’m at the end of my rope. Everything that I have worked for in my life, everything I have built up, is tumbling down like a house of cards.”

Читать дальше