|

Greenland. |

Baffin Land. |

| Transformation of a man into a seal. |

Rink, pp. 222, 224, 469. |

Kiviung, p. 621. |

| Men walking on the surface of the water. |

Rink, pp. 123, 407. |

Kiviung, p. 622. |

| Harpooning a witch. |

Rink, p. 372. |

Sedna, p. 604. |

| Erqigdlit. |

Rink, pp. 401 et seq. |

Adlet, p. 637. |

| Sledge of the man of the moon drawn by one dog. |

Rink, pp. 401, 442. |

Qaudjaqdjuq, p. 631, and The flight to the moon, p. 598. |

| Origin of the salmon. |

Cranz, p. 262. |

Ititaujang, p. 617. |

| Arnaquagsaq. |

Rink, pp. 150, 326, 466. |

Sedna, p. 583. |

| Origin of the thunder. |

Cranz, p. 233; Egede, p. 207. |

Kadlu, p. 600. |

The following is a comparison between traditions from Alaska and the Mackenzie and those of the Central Eskimo:

| Traditions from Alaska and the Mackenzie: |

Traditions of the Central Eskimo: |

| Men as descendants of a dog, Murdoch, op. cit., 594. |

Origin of the Adlet and white men, p. 637. |

| The origin of reindeer, Murdoch, op. cit., p. 595. |

Origin of the reindeer and walrus, p. 587. |

| The origin of the fishes, Murdoch, op. cit., p. 595. |

Ititaujang, p. 617. |

| Thunder and lightning, Murdoch, op. cit., p. s595. |

Kadlu the thunderer, p. 600. |

| Sun and moon, Petitot, op. cit., p. 7. |

Sun and moon, p. 597. |

| Orion, Simpson, p. 940. |

Orion, p. 636. |

The table shows that the following ideas are known to all tribes from Alaska to Greenland: The sun myth, representing the sun as the brother of the moon; the legend of the descent of man from a dog; the origin of thunder by rubbing a deerskin; the origin of fish from chips of wood; and the story of the origin of deer.

It must be regretted that very few traditions have as yet been collected in Alaska, as the study of such material would best enable us to decide upon the question of the origin of the Eskimo.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

The Eskimo exhibit a thorough knowledge of the geography of their country. I have already treated of their migrations and mentioned that the area they travel over is of considerable extent. They have a very clear conception of all the countries they have seen or heard of, knowing the distances by day’s journeys, or, as they say, by sleeps, and the directions by the cardinal points. So far as I know, all these tribes call true south piningnang, while the other points are called according to the weather prevailing while the wind blows from the different quarters. In Cumberland Sound uangnang is west-northwest; qaningnang (that is, snow wind), east-northeast; nigirn, southeast; and aqsardnirn, the fohn-like wind blowing from the fjords of the east coast. On Nettilling these names are the same, the east-northeast only being called qanara (that is, is it snow?) In Akudnirn uangnang is west-southwest; ikirtsuq (i.e., the wind of the open sea), east-northeast; oqurtsuq (i.e., the wind of the land Oqo or of the lee side, southeast; and avangnanirn (i.e., from the north side along the shore), the northwestern gales. According to Parry the same names as in Cumberland Sound are used in Iglulik.

If the weather is clear the Eskimo use the positions of the sun, of the dawn, or of the moon and stars for steering, and find their way pretty well, as they know the direction of their point of destination exactly. If the weather is thick they steer by the wind, or, if it is calm, they do not travel at all. After a gale they feel their way by observing the direction of the snowdrifts.

They distinguish quite a number of constellations, the most important of which are Tuktuqdjung (the deer), our Ursa Major; the Pleiades, Sakietaun; and the belt of Orion, Udleqdjun.

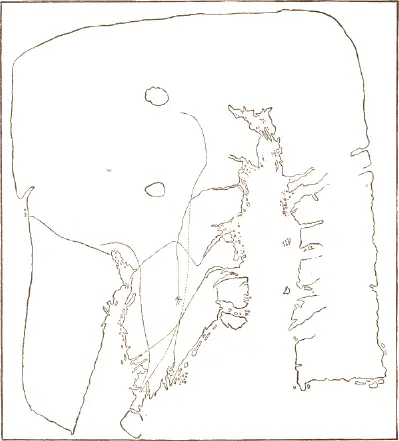

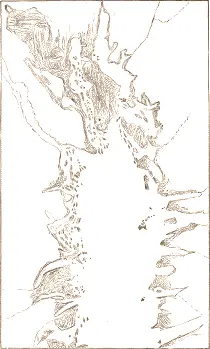

CUMBERLAND PENINSULA, DRAWN BY ARANIN, A SAUMINGNIO.

ESKIMO DRAWINGS.

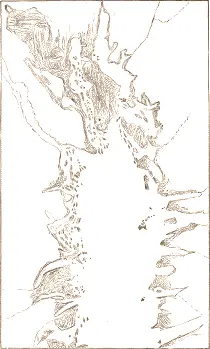

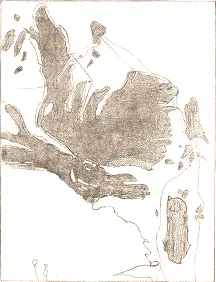

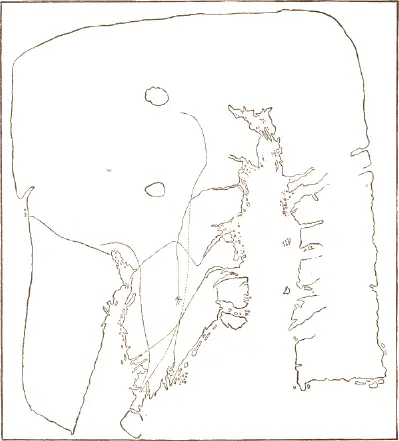

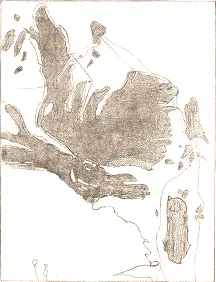

As their knowledge of all the directions is very detailed and they are skillful draftsmen they can draw very good charts. If a man intends to visit a country little known to him, he has a map drawn in the snow by some one well acquainted there and these maps are so good that every point can be recognized. Their way of drawing is first to mark some points the relative positions of which are well known. They like to stand on a hill and to look around in order to place these correctly. This done, the details are inserted. It is remarkable that their ideas of the relative position and direction of coasts far distant one from another are so very clear. Copies of some charts drawn by Eskimo of Cumberland Sound and Davis Strait are here introduced (Plate IV, p. 643, and Figs. 543–546). A comparison between the maps and these charts will prove their correctness. Frequently the draftsman makes his own country, with which he is best acquainted, too large; if some principal points are marked first, he will avoid this mistake. The distance between the extreme points represented in the first chart (Fig. 543) is about five hundred miles.

Fig. 543. Cumberland Sound and Frobisher Bay, drawn by Itu, a Nugumio.

(Original in the Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.)

Fig. 544. Cumberland Sound and Frobisher Bay, drawn by Sunapignang, an Oqomio.

Fig. 545. Cumberland Sound, drawn by Itu, a Nugumio.

Fig. 546. Peninsula of Qivitung, drawn by Angutuqdjuaq, a Padlimio.

The Eskimo have a sort of calendar. They divide the year into thirteen months, the names of which vary a great deal, according to the tribes and according to the latitude of the place. The surplus is balanced by leaving out a month every few years, to wit, the month siringilang (without sun), which is of indefinite duration, the name covering the whole time of the year when the sun does not rise and there is scarcely any dawn. Thus every few years this month is totally omitted, when the new moon and the winter solstice coincide. The name qaumartenga is applied only to the days without sun but with dawn, while the rest of the same moon is called siriniktenga. The days of the month are very exactly designated by the age of the moon. Years are not reckoned for a longer space than two, backward and forward.

a , b , c , e Drawn by Aisē´ang, a native of Nuvujen.

Читать дальше