The handicraft of the Navaho is seen at its best in their blanketry, which is one of the most important industries of any Indians within our domain. The greater portion of the wool from their hundreds of thousands of sheep is used in weaving, and in addition a considerable quantity of commercial yarn is employed for the same purpose. The origin of the textile art among the Navaho is an open question. It is probable that they did not learn it from anyone, but that it developed as a part of their domestic culture. It is contended by some that the early Spanish missionaries taught the Navaho to weave; but why should the white man be accredited with this art? The mummies found in the prehistoric cliff-ruins of the Navaho country are wrapped in cloth finer than any ever produced with a Navaho loom, and no doubt now remains that Pueblo people were incorporated by the Navaho in ancient times.

The blankets made in earlier days, say from fifty to a hundred and fifty years ago, are beautiful examples of primitive handicraft. The body of a so-called bayeta blanket was woven of close-spun native wool, dyed dark blue, while the red pattern was from the ravellings of Spanish bayeta. Much of the beauty of the old blankets is due to the mellowing of the native colors by age, but practically none of these rare examples are to be found among the Navaho at the present time. The blankets of to-day may be roughly divided into three classes: 1. Those made from the close-spun native yarn dyed in the old colors and woven in the simple old patterns; when aged they closely resemble the old bayeta blankets. 2. Blankets woven in a great variety of designs from coarse, loose-spun yarn dyed with commercial dyes of many shades; these are the Navaho blankets of commerce. 3. Those woven from commercial or "Germantown" yarn; they are of fine texture and sometimes beautiful, but lack interest in that their material is not of Indian production. Fortunately the decrease in the demand for blankets woven of commercial yarn is discouraging their manufacture.

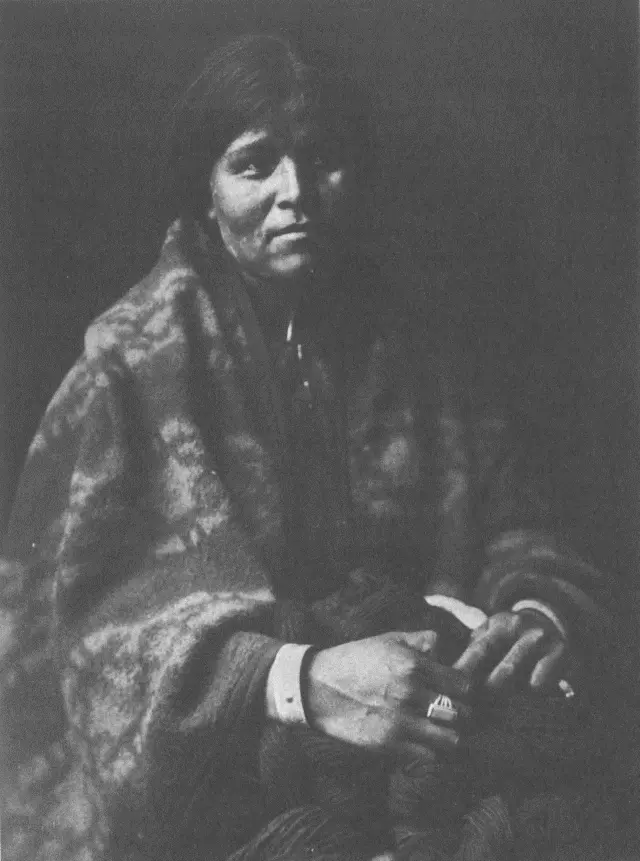

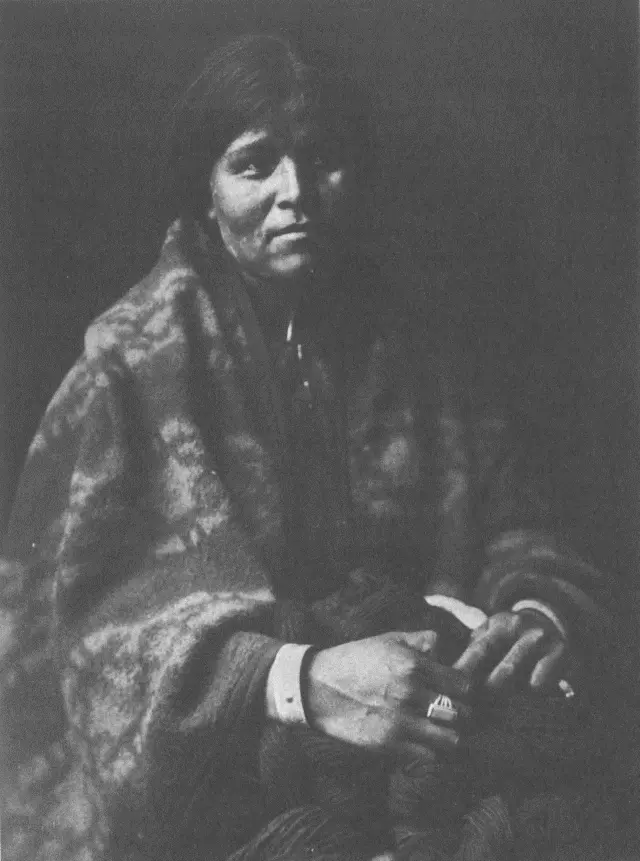

The Navaho woman weaves her blanket not so much for profit as for love of the work. It is her recreation, her means of expressing imagination and her skill in execution. Civilized women may write books, paint pictures, or deliver ringing addresses; these are unknown worlds to the Navaho woman: but when after months of labor she finishes a blanket, her pride in her work of art is indeed well justified.

Because of their pastoral life the Navaho are not villagers. Their dome-shaped, earth-covered hogáns are usually grouped two or three in the same locality. The summer house is a rude brush shelter, usually made with four corner posts, a flat top of brush, and a windbreak of the same material as a protection against the hot desert siroccos. The hogán proper, used for storage during the summer, affords a warm and comfortable shelter to its occupants through the cold winters of their high altitude. When a hogán is built it is ceremonially consecrated, and if an occupant should die in it, it is forever deserted and is called tsí̆ndi hogán, "evil house." No Navaho will go near such a house or touch anything taken from it. If a meal were cooked with decayed wood from a hogán a hundred years deserted, a Navaho, even if starving, could not be induced to partake of it. Thus strong are the religious beliefs of this primitive people.

The Blanket Maker - Navaho

The domestic equipment of the Navaho is simplicity itself and reflects the simple life of the tribe. Of household furniture there is none. The bedding consists usually of a few sheepskins; cooking utensils are earthen pots of their own making, and cups, knives, and spoons of civilization. Plates they do not need, as the family eat directly from the pot in which the food is cooked. The principal food is mutton, boiled, and corn prepared in many ways. Considerable flour obtained from traders is consumed; this is leavened slightly and made into small cakes, which are cooked over the embers like Mexican tortillas.

The women are an important factor in the Navaho tribe. The sheep usually, and the house, with all that pertains to it, always are the property of the wife. The independent spirit of the women, instilled by this incontestable property right, manifests itself throughout the tribe, and by reason of it the Navaho husband is not apt to seek an opportunity to criticise his wife so long as she is in a position to say, "If I and the hogán do not suit you, go elsewhere!" Polygamy is common, but as a rule the wives of one man are sisters, an arrangement conducive to domestic harmony.

Many of the Navaho men are skilled silversmiths. Every well-to-do Navaho possesses a silver belt consisting of a dozen or more wrought oval discs, each about two by three inches, fastened to a leather strap. Such a belt, weighing several pounds, is of course a valuable piece of property. The wearer may also have a broad silver bracelet set with turquoise, a heavy string of silver beads with a massive pendant of the same material, and a pair of deerskin leggings with a row of silver buttons on the outer side. Frequently their horses are gaily bedecked with bridles and saddles heavily weighted with silver ornaments. The long strap over the shoulder, from which the pouch of the medicine-man is suspended, is always studded with silver buttons. Mexican coins, especially the peso, are the principal source of all this silverwork, the Navaho preferring this coin to our own dollar because it is heavier. Buttons and beads also are made from American dimes and twenty-five cent pieces; the small beads from dimes, and the larger ones from two coins of the same value. They learned silversmithing from the Mexicans, but since their first lessons have developed a high degree of individuality in the art. While the metal-work of the Navaho at the present time is practically all in silver, only a few copper objects being made, their earliest work in metal was with iron, and occasionally an example of this is found. The silver and shell bead jewelry of the Navaho is his savings bank. During times of prosperity he becomes the possessor of all the jewelry his means afford, and when poor crops or long winters threaten distress he pawns it at a trader's, so that many of the traders often have thousands of dollars' worth of silverwork and shell beads on hand at one time. The system seems to be a very fair one, and in time of stress is certainly a boon to the impecunious Navaho.

The little pottery made by this people is an undecorated ware for utilitarian purposes only. For carrying water a gum-coated water bottle of basketry is in general use. Few baskets are made, and these are of but a single pattern—a flattish tray for use in ceremonies. Most of the baskets used by the Navaho in their ceremonies, however, are purchased from neighboring tribes, especially the Havasupai and the Paiute, who weave them primarily for purposes of trade. Such baskets must be of a prescribed pattern, with a break in the design at one side. When the basket is in use this side is always placed toward the east.

Most Navaho ceremonies are conducted, at least primarily, for the purpose of healing disease; and while designated medicine ceremonies, they are, in fact, ritualistic prayers. There are so many of these ceremonies that no student has yet determined their number, which reaches into scores, while the component ritual prayers of some number hundreds. The principal ceremonies are those that require nine days and nine nights in their performance. Of the many now known the names of nine are here given: Kléjĕ Hatál, Night Chant; 4Tzĭlhkí̆chĭ Hatál, Mountain Chant; Hozhónĭ Hatál, Happiness Chant; Natói Hatál, Shooting Chant; Toi Hatál, Water Chant; Atsósĭ Hatál, Feather Chant; Yoi Hatál, Bead Chant; Hochónchĭ Hatál, Evil-Spirit Chant; Mai Hatál, Coyote Chant. Each is based on a mythic story, and each has four dry-paintings, or so-called altars. Besides these nine days' ceremonies there are others whose performance requires four days, and many simpler ones requiring only a single day, each with its own dry-painting.

Читать дальше