The journeys people make to natural ecosystems, to places where the hand of humanity is hard to detect, are often too profoundly important to be reduced to dollars and cents ( Fig. 4.6). The forty days Moses spent in the desert, the walkabouts of Australian Aborigines, and perhaps the night you spent watching the tide ebb and flood are periods of spiritual recreation and revitalization that many people find of immeasurable value. For some people, particularly those who are pantheistic (i.e. believe that God is nature and nature is God), ecosystems provide far more than an aesthetic setting for these experiences. The ecosystems themselves, with their depth and complexity, are a source of inspiration, a vehicle for feeling connected to something larger and more permanent than one’s self. It is notable that all the world’s major religions advocate respect and stewardship for “creation.”

Figure 4.6 Many people visit natural ecosystems to feel a sense of spiritual renewal, for example by walking this path in Japan.

(Sean Pavone/Shutterstock)

Scientific and Educational Values

Ecology has become a very sophisticated science, but we still cannot hope to understand an ecosystem fully. This dilemma is apparent when you think of ecology as the apex of a pyramid with biology as the next layer below, earth sciences such as geology and climatology forming the third layer, chemistry the fourth, and physics the foundation. Of course, ecologists do not need an intimate familiarity with quantum physics to be effective, but they do need a basic understanding of thermodynamics, electromagnetic radiation, and many other aspects of physics. In contrast, a physicist can be highly successful and understand nothing about ecology. The fact that ecosystems integrate so many phenomena makes them a focal point for scientists trying to monitor how the Earth is changing, particularly in response to human activities. This feature also means that ecosystems are fascinating models for researchers interested in complex systems, for example by modeling how carbon moves through ecosystems to better predict global climate change (Harris et al. 2014).

Ecosystems are also wonderful models for showing children and adults how everything in the environment can be connected to everything else. Drawing lines between boxes to represent the functional relationships of those boxes can become an extremely complex exercise. Alternatively, it can be as simple as drawing lines between the sun, a plant, and an animal to form a food chain and then adding more boxes and lines to create a food web. How did that cup of coffee you are drinking get into your hands? In short, we can all learn a great deal from ecosystems.

The ecological interactions that are the basis of ecosystems are absolutely fundamental to life. Try to imagine a planet where dead things did not decompose, where water was not filtered through forests, or where plants did not replenish oxygen. Consequently, it is not really profound or insightful to say that ecosystems have ecological value. Nevertheless, it is extraordinary how often we try to place the well‐being of humanity over the well‐being of the ecosystems on which our lives ultimately depend.

Do all ecosystems have equal ecological value? No. Obviously, a large salt marsh will usually provide more ecological values than a small salt marsh, and, similarly, a dominant type of ecosystem such as spruce–fir forests will have more total ecological value than an uncommon type of ecosystem such as caves. Certain types of ecosystems may have a significantly greater importance to other nearby ecosystems than we would predict based on their area. We can call these keystone ecosystems, analogous to using the term keystone species for species with disproportionately significant ecological roles ( Chapter 3; deMaynadier and Hunter 1997). The long narrow shorelines where aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems intersect are an excellent example of this ( Fig. 4.7). Keystone ecosystems can also shape disturbance regimes that affect large areas by either inhibiting or facilitating the spread of a disturbance. To take two examples: a river can inhibit the spread of a fire, while certain types of woodlands that burn easily can facilitate the spread of fires to other ecosystems. Some of these keystone ecosystems are very small but have effects over large areas, for example, a cave that harbors a wide‐ranging colony of bats or a small pool that provides essential water for animals in a sizable landscape (M.L. Hunter 2017 ; Hunter et al. 2017; see Fig. 4.4).

Figure 4.7 The narrow riparian zones that border river shores are far more important ecologically, to both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, than you would predict given their narrow footprint. Thus they can be considered keystone ecosystems within a landscape. This is particularly evident in deserts where river shores are often a ribbon of green in an arid environment.

(Coconino National Forest/Public domain)

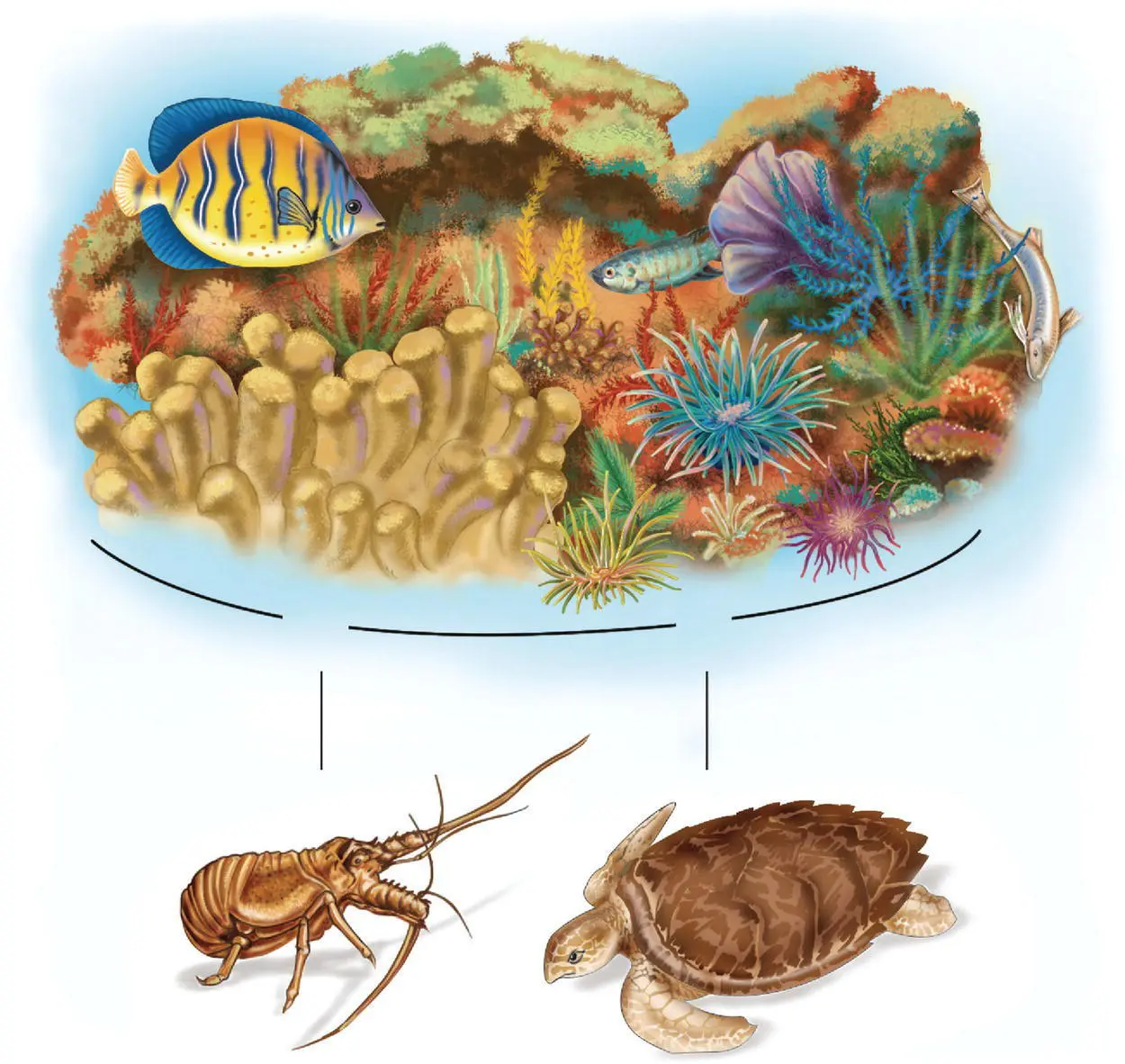

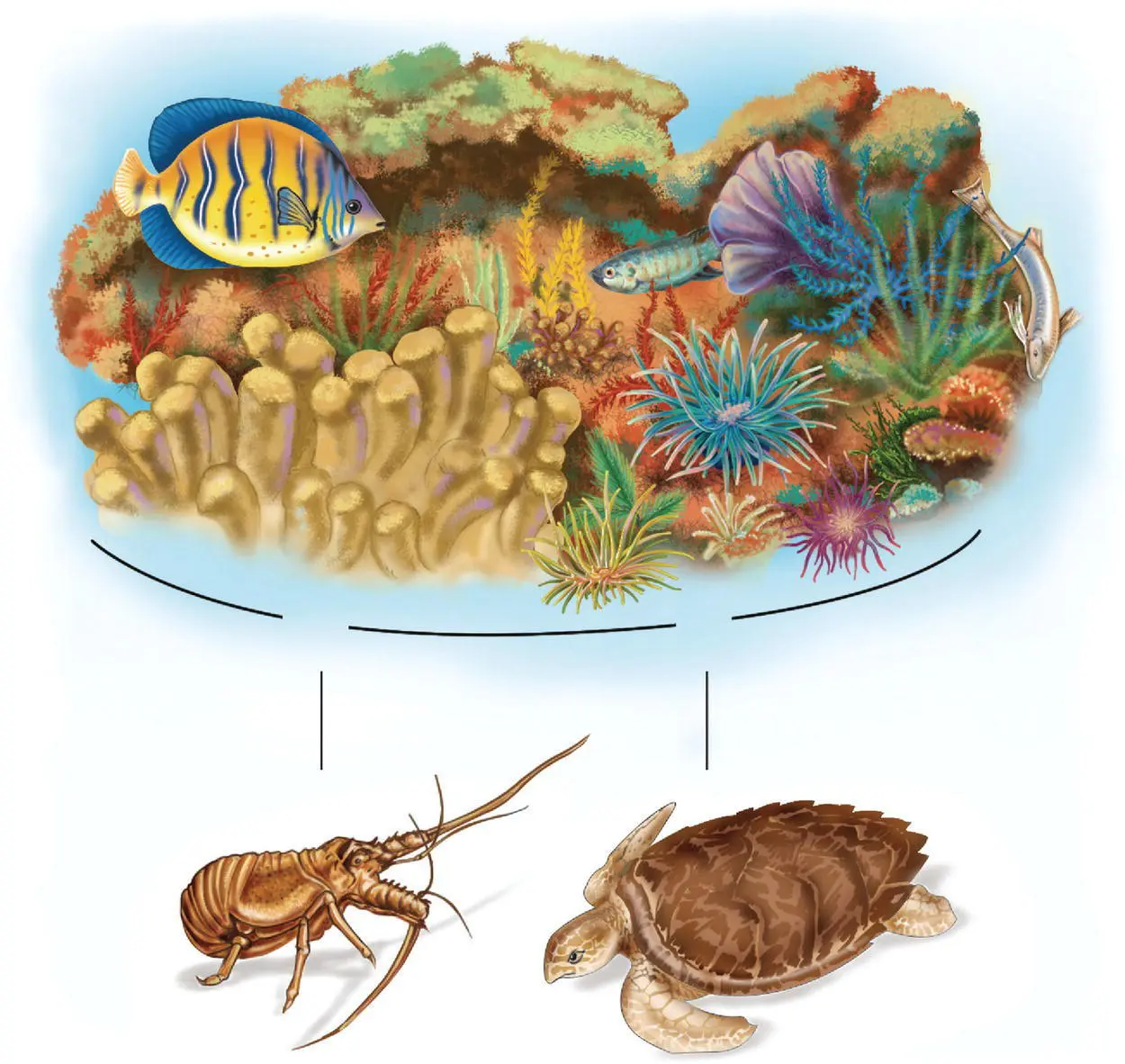

From the perspective of maintaining biodiversity at all levels – genes, species, and ecosystems – the single most essential value of ecosystems may be their strategic value. Conservation biologists have often proposed that by protecting a representative array of ecosystems, most species and their genetic diversity can be protected as well (Hunter 1991; Beier et al. 2015a). This idea is often described using a metaphor of coarse filters and fine filters first proposed by The Nature Conservancy (1982) ( Fig. 4.8). The coarse‐filter approach to conserving biodiversity is appealing because it is efficient and provides broad protection. It is efficient because, compared with the number of species in the world, there are relatively few different types of ecosystems and thus protecting a representative array of these is comparatively straightforward. It is broad because it will protect, to some degree, little‐known species such as invertebrates and fungi, even undescribed species, plus their genetic diversity. The Nature Conservancy (1982) originally estimated that 85–90% of species could be protected this way, although this seems optimistic based on the few empirical tests that have been undertaken (e.g. MacNally et al. 2002; Grantham et al. 2010).

Figure 4.8 The strategic value of ecosystems is illustrated by the coarse‐filter–fine‐filter approach to conserving biodiversity. Protecting a representative array of ecosystems constitutes the coarse filter and may protect most species. However, a few species will fall through the pores of a coarse filter because of their specialized habitat requirements or because they are overexploited. These species will require individual management, the fine‐filter approach. In this example, a coral reef ecosystem with all of its constituent species is protected by the coarse‐filter approach, but fine‐filter management is still required for the hawksbill turtle and spiny lobster.

Importantly, the coarse‐filter approach can be an effective strategy regardless of whether ecosystems are tightly connected systems or loose assemblages of species ( Fig. 4.3). It is only necessary that the distribution of species and their habitats have some degree of concordance so that a complete array of ecosystems will harbor a reasonably complete array of species (Hunter et al. 1988; Rodrigues and Brooks 2007). We will return to this point and the coarse‐filter approach in general in Chapter 11, “Protecting Ecosystems.” Finally, it is notable that some ecosystems are analogous to flagship species; that is, they elicit public concern about conservation writ large. Tropical rain forests and coral reefs are perhaps the best examples of this phenomenon, but others, such as traditional agricultural ecosystems with high cultural value, are emerging as a new emblem for biodiversity conservation ( Chapter 14, “Conservation near People”).

Читать дальше