Distinguishing ecosystems is also difficult because ecologists think about ecosystems at a variety of spatial scales. A pool of water that collects in a hole in an old tree and is home to some algae and invertebrates can be considered an ecosystem. At the other extreme, ecosystems are sometimes defined on the basis of the movements of wide‐ranging animals. When biologists speak of the Serengeti Ecosystem they are referring to an area of almost 27,000 km 2defined in large part by the habitat needs of a migratory wildebeest population (Rentsch and Packer 2015). At the largest known scale, the Earth’s entire biosphere can be considered an ecosystem.

The key thing to understand is that the term “ecosystem” is a conceptual tool that makes it easier for us to organize our understanding about ecological interactions and to communicate about it. For the purposes of this book we can think of ecosystems at a spatial scale that is easy to detect from an airplane, typically from a fraction of a hectare to a few hundred hectares. We can draw the boundaries between adjacent ecosystems where they will separate distinct sets of species. Conservationists then give priority to maintaining examples of the different types of ecosystems thus delineated; we cannot realistically expect to protect every individual ecosystem.

Just as it can be difficult to delineate particular ecosystems on the ground, it is also difficult to classify them into different types once they are delineated (Whittaker 1973). How do we decide if two different forests are the same type of forest ecosystem? Although there are several quantitative methods for assessing similarity of community composition, there is no standard level of similarity used to decide whether two ecosystems are of the same type ( Table 4.1). Despite the lack of universal standards, significant progress has been made for some countries (e.g. Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and United States) and regions (Latin America and the Caribbean) on developing vegetation classification schemes that are effectively terrestrial ecosystem classification systems (USNVC.org; Faber‐Langendoen et al. 2014). As depicted in Table 4.2, ecosystem classification is usually approached hierarchically. For example, at the highest level we could separate terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems; at a lower level freshwater, marine, and estuarine ecosystems; then freshwater ecosystems into lakes and rivers; and so on. However, there is no universally accepted system for doing this analogous to the kingdom‐phylum‐class‐order‐family‐genus‐species system.

Table 4.1 Relative abundance of species (percentages) in three hypothetical ecosystems. Based on the limited data presented, most ecologists would probably classify A and B as belonging to one type of ecosystem and C to a different type. Note that the similarity index (which has a range of 0 to 1) is much higher between A and B than between B and C or A and C. However, there is no standard level of similarity used to determine if two ecosystems are of the same type. (See Magurran 2004 for calculation of the Morisita–Horn similarity index, used here, and others)

| Ecosystem |

A |

B |

C |

| Black oak |

40 |

30 |

10 |

| White pine |

30 |

40 |

10 |

| Red maple |

20 |

10 |

10 |

| Yellow birch |

10 |

20 |

70 |

| Similarity index |

A vs B 0.96B vs C 0.54A vs C 0.40 |

Table 4.2 This example depicts how one type of forest nests within the levels of the International Vegetation Classification hierarchy for terrestrial vegetation.

Sources : NatureServe Explorer and The U.S National Vegetation Classification

| Class |

1: Forest & Woodland |

| Subclass |

1.B: Temperate & Boreal Forest & Woodland |

| Formation |

1.B.2: Cool Temperate Forest & Woodland |

| Division |

1.B.2.Na: Eastern North American Forest & Woodland |

| Macrogroup |

Appalachian‐Interior‐Northeastern Mesic Forest |

| Group |

Appalachian‐Allegheny Northern Hardwood ‐ Conifer Forest |

| Alliance |

Central & Southern Appalachian Rich Northern Hardwood Forest |

| Association |

Sugar Maple ‐ Yellow Birch ‐ Black Cherry Forest |

Geography also needs to be considered when classifying ecosystems. Two alkaline eutrophic lakes that share a very similar biota would probably be considered the same type of ecosystem even if they are hundreds of kilometers apart and on either side of a mountain range. On the other hand, if the mountain range was a geographic barrier for many species and the two lakes had quite different biotas we might decide that they are different types of ecosystems.

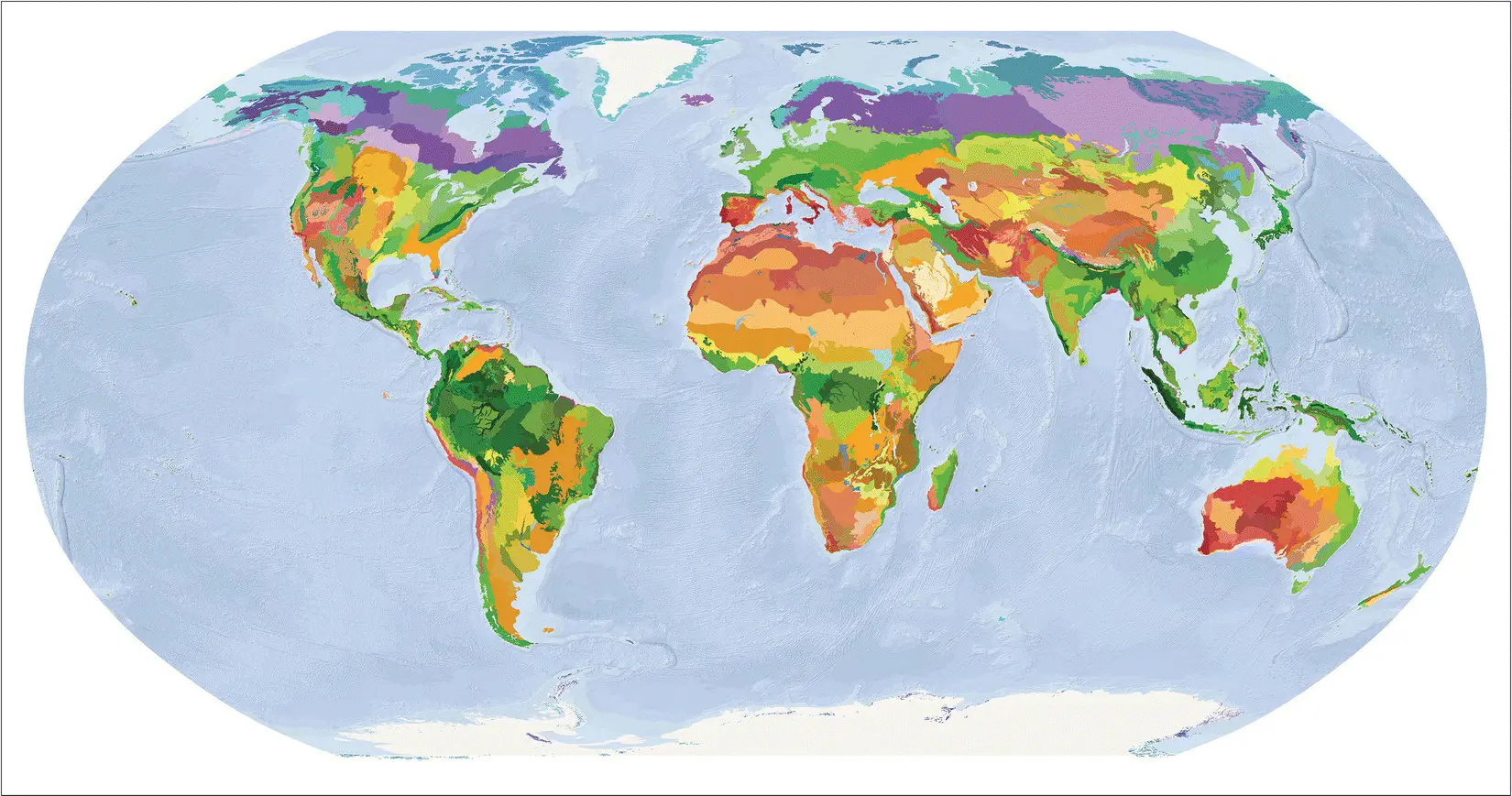

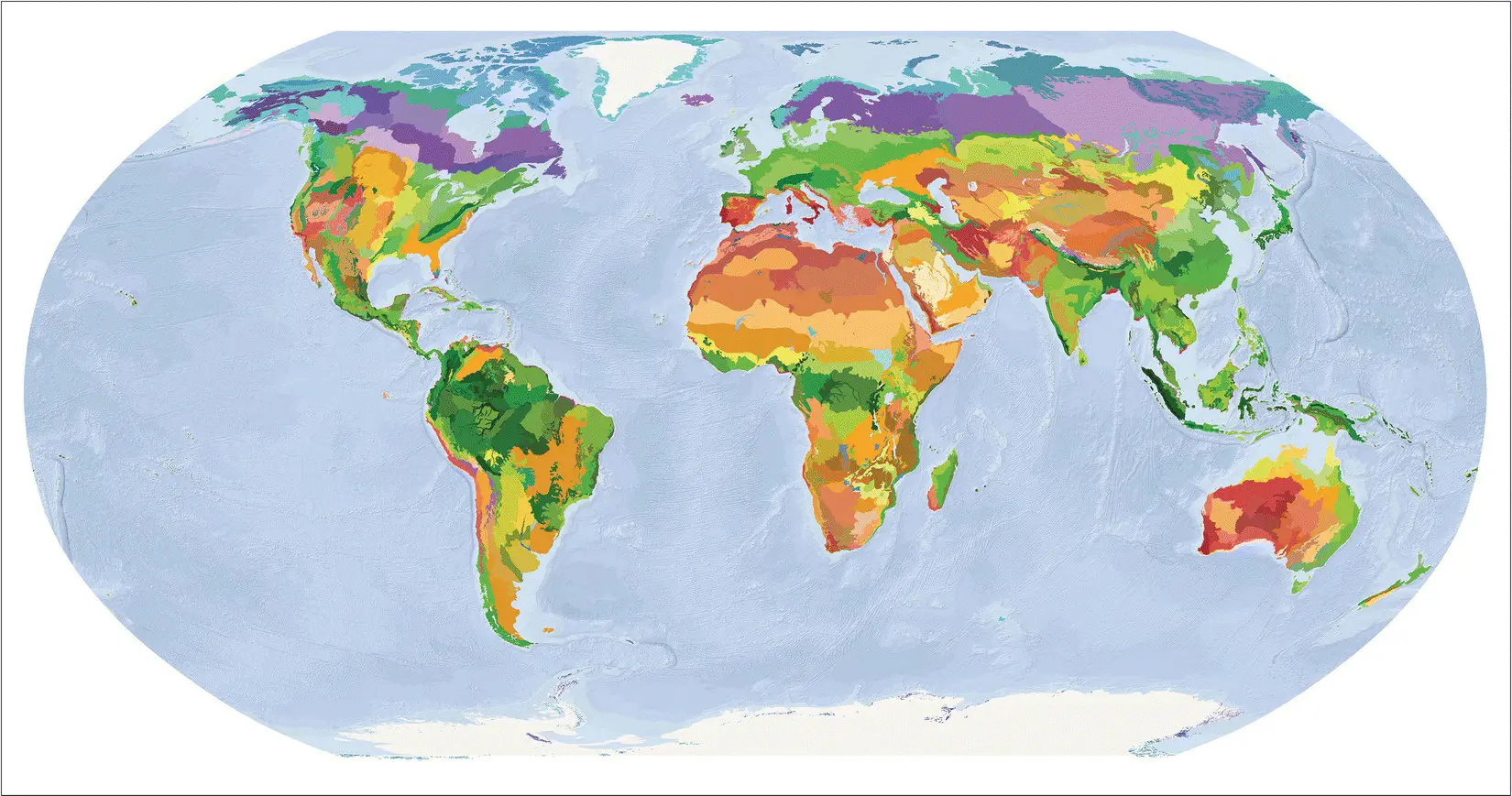

How can we recognize both the basic physical similarity of the two alkaline eutrophic lakes and the biological differences that occur because of their geographic separation? One approach involves dividing the world into regions based on biologically meaningful patterns that shape the distribution and abundance of species such as climatic zones, mountain ranges, oceans that isolate terrestrial biota, or continents that isolate marine biota. There are many examples of such maps and they use a variety of criteria and names such as ecoregions, ecoclimatic zones, biogeographic provinces, and biophysical regions (Bailey 1996 , 2005 ; Loveland and Merchant 2005). One set of maps originally created by World Wildlife Fund‐US and The Nature Conservancy delineated 867 terrestrial ecoregions (Olson et al. 2001, see Fig. 4.2for latest version), 426 freshwater ecoregions (feow.org; Abell et al. 2008), and 232 coastal marine ecoregions (Spalding et al. 2007). By using such maps we can recognize the differences that exist between the two lakes because they are in different ecological regions, but we could still recognize their basic similarity by calling them both alkaline eutrophic lakes.

Figure 4.2 This map depicts the Earth’s terrestrial ecoregions; see text about analogous maps for freshwater and coastal ecoregions and Dinerstein et al. (2017). An interactive version of this map is available at http://ecoregions2017.appspot.com.

From a conservation perspective we could largely avoid the issue by organizing conservation efforts for each ecological region. However, conservation efforts are usually organized around political units – states, provinces, nations – and political boundaries do not usually coincide with ecological boundaries.

Species cannot survive in isolation from other species; they are all part of some ecosystem. Therefore all ecosystems have value because the species they support have value. In other words, at a minimum the value of an ecosystem is the summation of the value of all its constituent organisms. This idea is simple enough, but it is not the end of the story. We must also consider that ecosystems probably have special attributes that emerge from interactions among the component species and make them valuable beyond the sum of species‐specific values. Let us consider each of the major types of values that we evaluated in Chapter 3from this perspective.

Whether or not ecosystems have intrinsic value independent of the intrinsic value of their constituent species is an issue that hinges on a complex and controversial question. Are ecosystems superorganisms composed of tightly connected, synergistic systems built around a set of closely coevolved species? Or are they based on a loose assemblage of species that happen to share similar habitat needs and end up interacting with one another to varying degrees because they are in the same place at the same time ( Fig. 4.3)? This question has stimulated ecologists for decades (McIntosh 1980). Undoubtedly, the truth lies somewhere between the poles presented here and varies somewhat from ecosystem to ecosystem, but for our purposes it is sufficient to note that the closer ecosystems lie to the “tightly connected” pole of the spectrum, the easier it is to acknowledge that they have intrinsic value.

Читать дальше