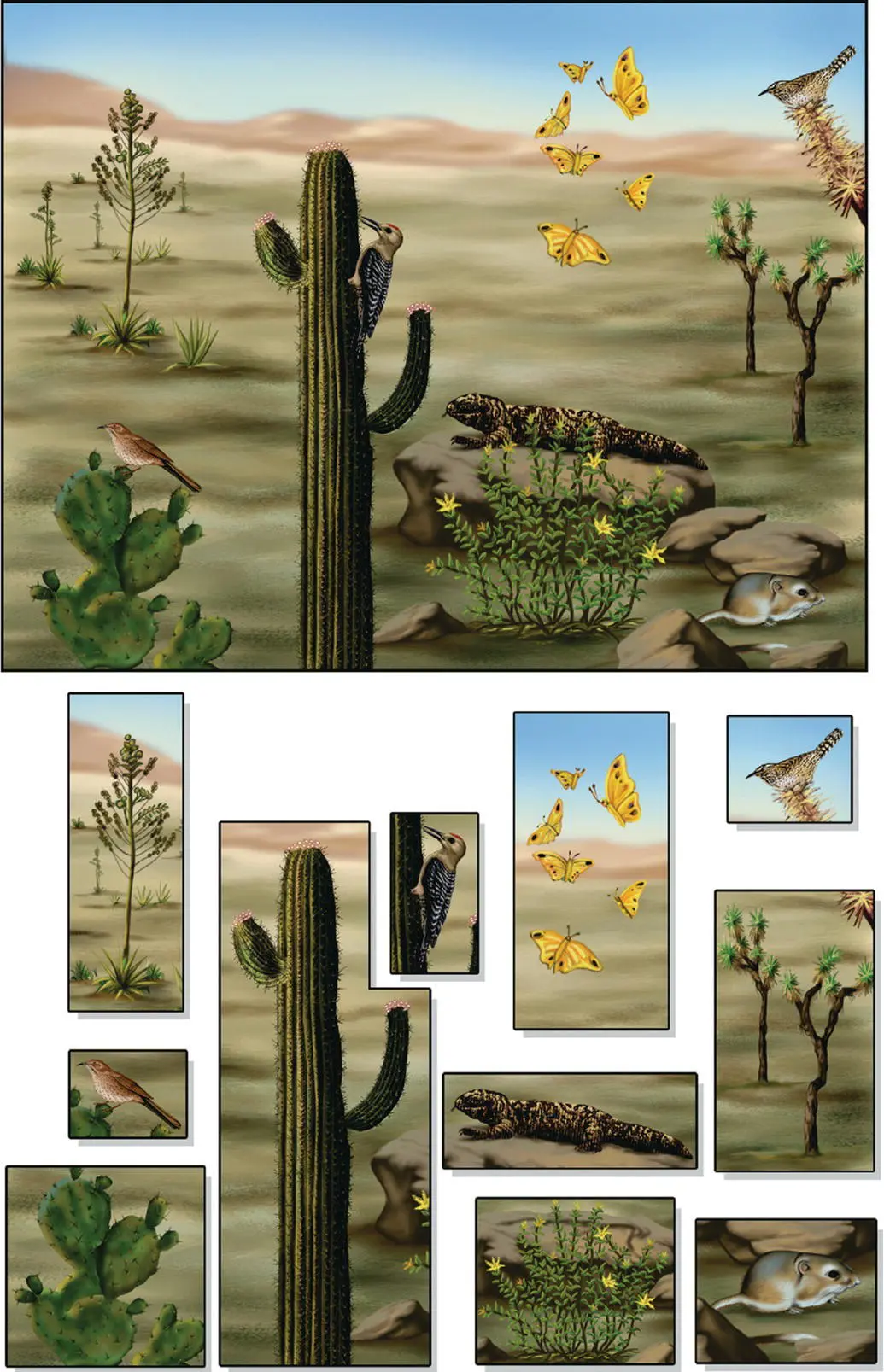

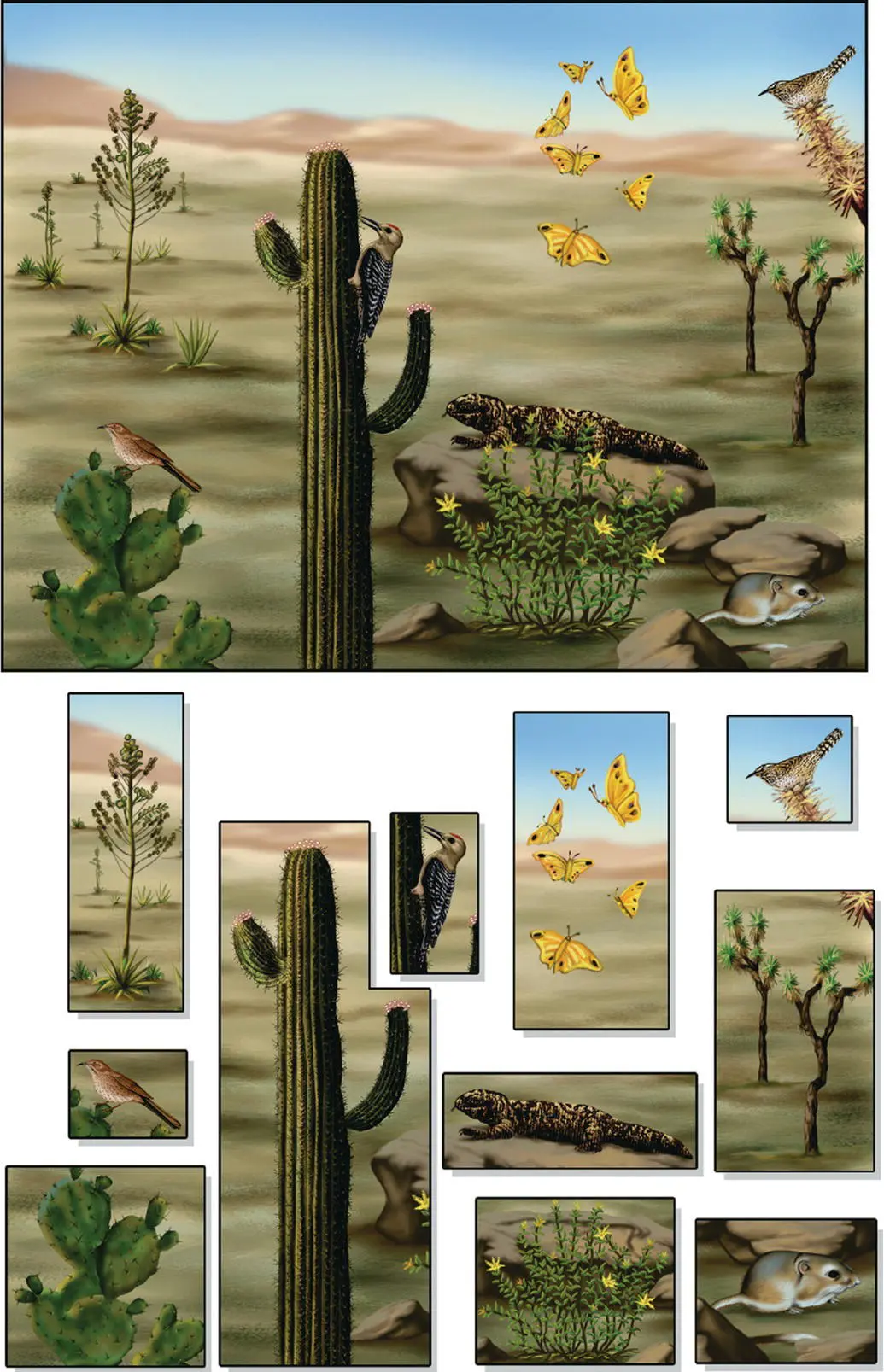

Figure 4.3 Are ecosystems tightly connected systems of closely coevolved species, or are they a loose assemblage of species that happen to share similar habitat needs and end up interacting with one another?

If ecosystems do have intrinsic value, then conservationists need to protect some examples of each different type of ecosystem, especially those that are in danger of disappearing. Some types of ecosystems are rare because they occur only in uncommon environments. For example, cool forests and alpine areas are rare in Africa because the continent has relatively few mountains tall enough to support these ecosystems (Kingdon 1989). Other ecosystem types have become uncommon because of human activities. In particular, most types of forest and grassland ecosystems associated with fertile soils and benign climates have largely been converted to agricultural lands.

Conservationists recognize the importance of protecting a representative array of ecosystems, especially those that are extensive and undegraded (Watson et al. 2020), but they have not yet developed many endangered ecosystem lists, especially ones with legal status analogous to various official endangered species lists (see Fig. 4.4and Table 4.3for examples). An ambitious effort to create a global “Red List of Ecosystems” is underway; see iucnrle.org, Keith et al. (2013) and J.P. Rodriguez et al. (2015). Political hurdles may be paramount, but the challenges of classifying ecosystems discussed previously also play a role (Boitani et al. 2015). Are the spruce–fir forests that occur on a few summits in the southern Appalachians a different type of ecosystem from the spruce–fir forests that stretch across Canada? If so, they are a very rare ecosystem; if not, they are just a peripheral variation of one of the planet’s most widespread ecosystems. Decisions like this are absolutely critical if you are trying to protect ecosystems for their intrinsic values, but they are not nearly so important if your focus is on the instrumental values of ecosystems.

Figure 4.4 Some types of ecosystems are rare because most examples have been destroyed, for example tall grass prairies. Others, like Mediterranean temporary pools, were always a small portion of the landscape and have shrunk further. This is particularly unfortunate given their rich flora and fauna, especially invertebrates and amphibians that thrive where there are no fish.

(Viktor Loki/Shutterstock)

Table 4.3 A few governments have begun the process of protecting endangered types of ecosystems by listing types that are rare or threatened. Listed here are a few examples from four much longer lists.

Sources : Australia: deh.gov.au/epbc; Europe: europa.eu/legislation_summaries/environment/nature_and_biodiversity/l28076_en.htm; RSA: Mucina and Rutherford 2006; USA: Noss et al. 1995

| Australia |

| Aquatic root mat community in caves of the Swan Coastal Plain Cumberland Plain shale woodlands Eastern Stirling Range montane heath and thicket Lowland native grasslands of Tasmania Parched wetlands of the Wheatbelt region Temperate highland peat swamps on sandstone |

| Europe |

| Inland salt meadows Mediterranean temporary ponds Temperate Atlantic wet heaths Xeric sand calcareous grasslands Fennoscandian deciduous swamp woods Eastern white oak woods |

| South Africa |

| Atlantic sand fynbos Bloemfontein dry grassland Cape vernal pools Ironwood dry forest Legogote sour bushveld Lowveld riverine forest Swartland alluvium fynbos |

| United States |

| Longleaf pine forests and savannas in the southeastern coastal plain Tallgrass prairie east of the Missouri River and on mesic sites across range Wet and mesic coastal prairies in Louisiana Coastal strand in southern California Ungrazed sagebrush steppe in the Intermountain West Streams in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain |

The idea that ecosystems have instrumental values has a long history but the concept really took root with an important book, Nature’s Services (Daily 1997), that examined “ ecosystem services ” in depth. This term is a bit too narrow in that the concept encompasses all biodiversity values, not just those that are tightly tied to ecosystems, and both products (e.g. timber) as well as services (e.g. renewal of clean air and water). However, there is virtue in simplicity and “ecosystem services” has become a major rallying point for conservation activities that improve human welfare (Lele et al. 2013). Having covered the instrumental values of species in Chapter 3, here we will focus on those exhibited at the ecosystem level.

When we think of the economic values of ecosystems in terms of goods and services, the material goods provided by ecosystems can generally be accounted for by summing the goods provided by various species such as the lumber from tree species, the food from fish species, and so on. With services, however, whole ecosystems are often the logical “source of production.” For example, wetlands are often used for treatment of wastewater, a service that would be quite expensive to duplicate with a treatment plant (Gude et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2015), and can play a key role in mitigating floods (Acreman and Holden 2013). Dune and salt‐marsh ecosystems provide an invaluable service during coastal storms by buffering upland areas. Coastal wetlands export nutrients and organic matter to adjacent estuaries where they support economically valuable fisheries ( Fig. 4.5). Forests export high‐quality water to aquatic ecosystems and urban water supplies. This list could go on and on because for virtually every ecosystem we could identify services that would be very expensive to replace artificially. Access to the recreational services of ecosystems is the basis for an enormous array of commercial enterprises. These can be as simple as bus trips for city dwellers to visit a forest or lake on a Saturday afternoon, or they can be as all‐inclusive as completely catered “ecotours” to coral reefs, tropical forests, Antarctic islands, and so on (Honey 2008).

Figure 4.5 Relatively few species can tolerate the special conditions of salt marshes, but those that do create ecosystems of great importance. Salt marshes buffer upland areas from ocean storms. They also export large amounts of organic matter to adjacent estuaries, which constitutes a key component of the estuarine food web.

(Trish Hartmann/Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

The economic values of ecosystems for both goods and services were compiled and a grand tally of their economic value estimated by multiplying a value‐per‐hectare figure for each major type of ecosystem by the total global area of that ecosystem (Costanza et al. 1997a). The estimate of $33 trillion per year was considered an average figure because of the nature of various uncertainties within a range of $16 to $64 trillion. To put these figures in perspective, the gross national products of all the world’s nations totaled about $18 trillion at that time.

Читать дальше