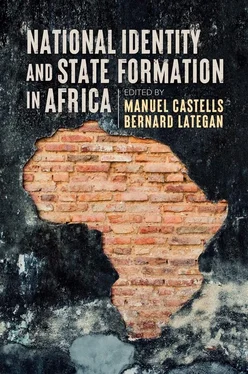

Chapter 1 Introduction: Identity, Networks and State Formation in Africa

Manuel Castells and Bernard Lategan

The contradictory dynamics reshaping our world in the twenty-first century are characterized by the relationship between globalization and identity. On the one hand, the core activities that define the economy, technology and geopolitical power are organized around a global network of glocal networks. This is the case for financial markets, international trade, multinational manufacturing, advanced business services, research and technology, military strategies, media production and distribution, and internet communication. On the other hand, historically rooted cultural identities, at the source of the creation of meaning, are stronger than ever everywhere, as a counterpart to the global flows of capital and communication that attempt to overwhelm the specificity of every human community, to merge them in a global culture that ultimately rationalizes the domination of certain values, multinational economic actors and political institutions in an interconnecting network of local and global hierarchies. To no avail. Deprived of their ability to exercise control over global forces, people around the world retreat into their own values, asserting their identity and using whatever means available to them to claim their autonomy vis-à-vis global networks that embody domination under the cover of instrumentality. In doing so, they are also mobilizing their energies to maximize their interest in the interconnecting global and local hierarchies in which they find themselves.

The world in the twenty-first century is dominated by conflicts of identity: religious, national, territorial, racial, ethnic, age, gender, ideological and otherwise. The failure to recognize the essential role of identity in structuring social life creates a key epistemological obstacle to understanding our world. The ideology of the Enlightenment (which recognizes identity only in the categorization of its opposites) that refuses to see identity as the source of self-definition, in favour of the abstract construction of the citizen, defined by the state, leads to intellectual dead ends. Even if we do not like the primacy of identity, we must acknowledge and deal with it as social scientists and philosophers.

This fundamental development can be observed everywhere, not just in the previously dominated/colonized areas of the world, but also in the United States and in Europe. The American nationalist movement, built around Trump, or the mobilization for Brexit in the UK, are clear expressions of the power of identity – a trend that often leads to xenophobia.

Sources of collective identity (always a cultural construction) are diverse. One of the most significant in the socio-political evolution of our societies is national identity. National identity is the set of interrelated cultural attributes that provide meaning and self-recognition to a collective of humans that define themselves as a national community. The term ‘national’ specifies the aspiration of this community to be acknowledged as a distinct social group that transcends primary ascription attributes, such as ethnic or territorial, and to emphasize their shared experience over time and space. It is suggestive of a congruence between polity and culture. Fundamentally, nations are cultural communities, but they are not ‘imagined’; they are constructed with the materials of history and geography.

Nations must be clearly distinguished, conceptually and practically, from states, because states are political-institutional constructions, sometimes derived from a pre-existing nation, but more often resulting from the integration/annexation of several nations, that are fused, through political domination, into a given state. In fact, the nation-state of the modern era is an exception in the high diversity of institutional constructions resulting from the interaction between nations and states, from city states to imperial states, and from communal institutions to tribal confederations. The multicultural, multi-ethnic and multi-lingual composition of many (if not the majority of; cf. Welsh 1993) states gave rise to the idea of ‘multinational states’ (cf. Peleg 2007; Kraus 2008).

Moreover, when a nation-state is constituted, it defines a new identity: citizenship as established by the state. Citizenship tends to reflect the cultural identity of the nation that prevailed in the construction of the state, although in some cases, the project of state formation may include the negotiated recognition of pluri-national states – always a fragile construction because it does not necessarily respect equal access to the resources of the state. This is where federalism becomes a critical intermediate institution between the state and the nation. In some situations (South Africa is one example), despite the formal structure of a unitary state, many ethnic groups would rather understand and speak of themselves as nations. This is especially the case in previously colonized countries who see themselves obliged to operate under the label of modern nation-states, post-colonialism.

The existence of nations without states is widely acknowledged as a result of the diversity of the historical process. The most often cited examples are Scotland, Wales, Quebec, Catalonia, Euskadi, Kurdistan, Palestine (still without a state), Tibet and multiple quasi-national communities still entangled in struggles, violent or not, in their aspiration to statehood. The boundaries between nationhood and statehood are fluid and often change over time. Moreover, nations tend to persevere longer than states, the most important examples being the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

The role of identity in both founding and dissolving the institutions of the state can be better understood by differentiating three major types of national identities: resistance identity, legitimizing identity and project identity.

Resistance identity occurs when a materially produced, culturally experienced collective identity is not recognized in the institutions of the state, when states are formed on different constellations of culture and power. Then, social movements and political projects emerge in what could be a protracted confrontation that results in a new institutional system. However, when the force of the existing states prevails, resistance identity becomes the source of multiple forms of negation of the dominant state institutions, sometimes for centuries. Pluri-national states based on consensus (such as Switzerland or Canada) become stable institutions that weave a new political actor by sharing in the construction of meaning. States that include various nations without recognition of national rights are periodically torn by confrontations, often intensified by ethnic or religious conflicts.

Legitimizing identity is the collective identity produced by the state on the basis of a period of sharing the building of common institutions, usually under the predominance of one particular identity, and a given set of interests. Most of the nation-states created in the last three centuries follow this pattern, so that national identities are constructed by the state, with the education system being primordial in this construction. The school of the French Third Republic epitomizes this cultural hegemonic development.

Project identity is the collective identity defined by a process of becoming rather than that of being. It is the national or pluri-national community that people would like to be, not as the expression of a pre-existing cultural community but as the will of discovering new institutional forms on the basis of a set of values in the making. The project of the European Union would qualify as a national identity project. The United States of America was also built on the quest for a common goal – not without conflicts, as manifested by the atrocious civil war fought not only due to economic interests but also to the divergent fundamental values of the two national identity projects that clashed on the battlefield.

Читать дальше