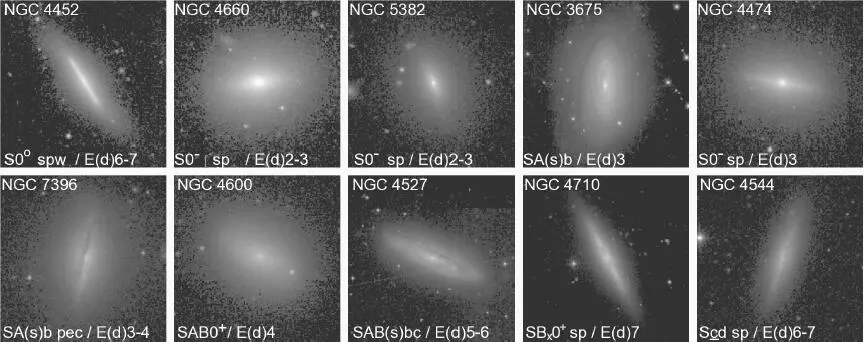

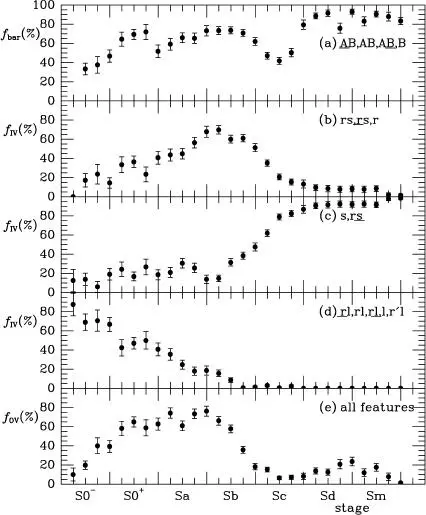

1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...17 Most spiral and S0 galaxies do not have dominant classical bulges, but many have a two-component disk: the thin disk , which has a vertical scale height of a few hundred pc, and the thick disk , which shares the same plane with the thin disk but has a vertical scaleheight of about 1 kpc. Especially in spirals, the two disks can have very different stellar populations, with population I material occupying the thin disk and population II material occupying the thick disk. As for embedded disks, thin and thick disks are recognized in CVRHS classifications by combining a normal stage classification with an E(d) or E(b) classification as in, for example, S0 −sp/E(d)7. In this case, the “S0 −sp” part refers to the thin disk and determines the stage index T of the galaxy. The “E(d)7” part refers to the thick disk, whose apparent flattening and isophotal character (cuspy or boxy) are judged from a color display. Note that thick disks may have cuspy, boxy or perfectly elliptical isophotes, the latter requiring no (d) or (b) added to the classification.

Figure 1.22. Embedded disks and thick/thin disks. The main embedded disk cases shown are NGC 4660, NGC 5382, NGC 3675 and NGC 4474, and the thick/thin disk examples include NGC 4452, NGC 4527, NGC 4710 and NGC 4544

1.9. Morphology of interacting and merging galaxies

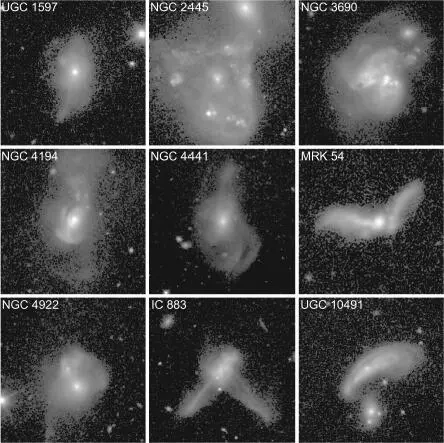

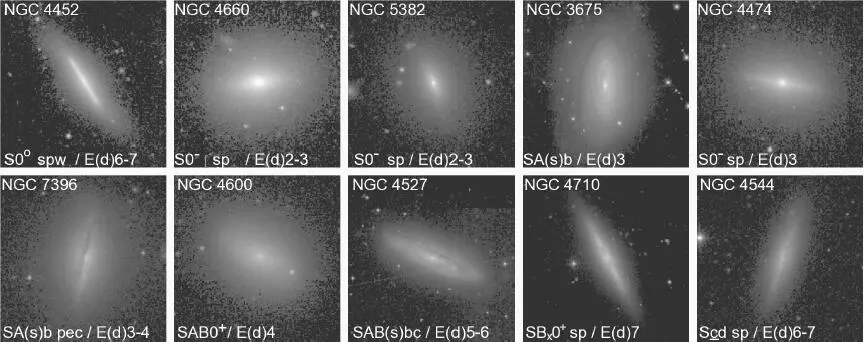

Interacting and merging galaxies make up about 2–4% of nearby galaxies (Knapen and James 2009) and are often unclassifiable in any standard Hubble-based morphological bins. Figure 1.23shows several examples, all of which are classified as Pec (merger) in the CVRHS system. Distorted shapes, tidal tails, sharp edges (“shells” or “ripples”; e.g. Schweizer and Seitzer 1988), multiple nuclei, and in some cases enhanced star formation characterize these objects. Although major mergers of two spiral galaxies have been thought to generally lead to an elliptical galaxy as a remnant (e.g. Schweizer 1982), more recent numerical studies have shown that a disk galaxy can also be a remnant of such mergers (Athanassoula et al . 2016).

Figure 1.23. Examples of interacting and merging galaxies

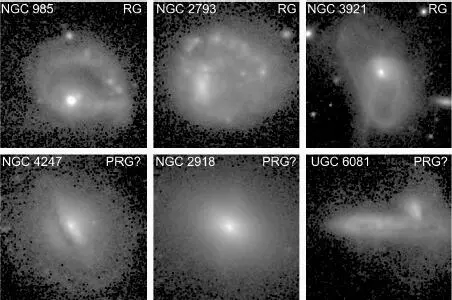

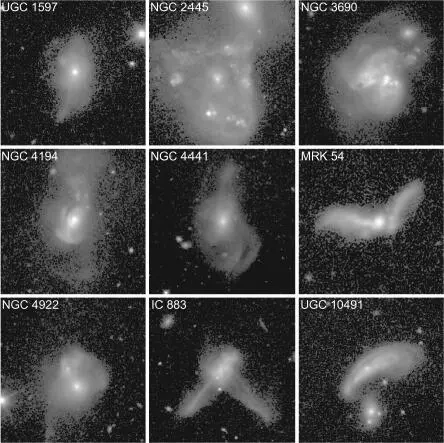

The types of rings in normal galaxies that define inner, outer and nuclear varieties are likely features that result from internal dynamics ( section 1.12). Figure 1.24shows examples of the extremely rare types of ring-like features that likely result from a cataclysm, such as a galaxy interaction or encounter. Collisional ring galaxies (RGs; upper frames in Figure 1.24) are one type of cataclysmic ring; these are thought to result from a head-on collision between a disk galaxy and a companion (Appleton and Struck-Marcell 1996). Polar ring galaxies (PRGs; lower frames in Figure 1.24) are a second type; these are thought to originate from the disruption of a small satellite galaxy along a polar orbit around a more massive disk galaxy (Schweizer et al . 1983). None of the examples of this type of feature shown in Figure 1.24are certain cases. The possible PR feature in NGC 2918 is very faint but favorably oriented nearly edge-on (Whitmore et al . 1990). The possible case in NGC 4247 may be nearly face-on and less clearcut.

Figure 1.24. Possible examples of cataclymic ring galaxies. Top row: collisional ring galaxies. Bottom row: polar ring or inclined ring galaxies

1.10. General properties along the CVRHS sequence

1.10.1. Morphological systematics

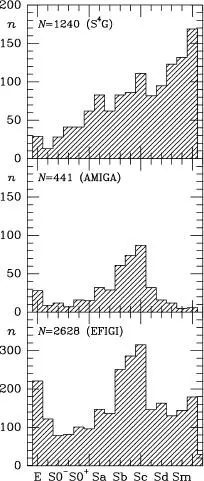

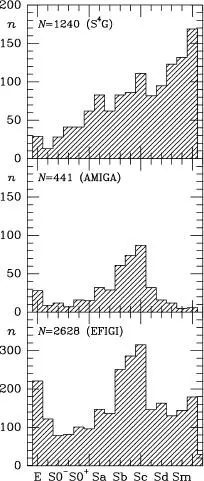

The classification of a large sample of galaxies in the CVRHS system allows investigation of the systematics of different morphological types and classes, i.e. how aspects of morphology might vary with stage and family. Figure 1.25first shows the distribution of stages for three galaxy samples: (a) a sample of 1240 galaxies from the Spitzer Survey of Stellar Structure in Galaxies (S 4G; Buta et al . 2015); (b) a sample of 441 galaxies from the Analysis of the Interstellar Medium in Isolated Galaxies (AMIGA; Buta et al . 2019; Verdes-Montenegro et al . 2005); and (c) a sample of 2,628 galaxies from the Extraction of the Forms of Galaxies from Images survey (French acronym: EFIGI; Buta 2019; Baillard et al . 2011). Each plot is restricted to galaxies inclined at ≤60°. The three graphs show how the distribution of stages depends sensitively on the selection criteria for a given sample. The S 4G sample is distance-limited and used 21 cm radial velocities to judge distances; this accounts for the significant emphasis of this sample on extreme late-type (Sd-Sm) spirals and Magellanic irregulars (Im). The EFIGI sample was selected largely on the basis of angular diameter and emphasizes mainly Sb-Sc spirals. The AMIGA sample of isolated spirals is similar in showing an emphasis on Sb-Sc spirals.

Figure 1.25. Distribution of CVRHS stages from (a) Buta (2019; EFIGI), (b) Buta et al. (2019; AMIGA) and (c) Buta et al. (2015; S 4 G). The histograms are each restricted to relatively face-on galaxies (i ≤ 60 ° )

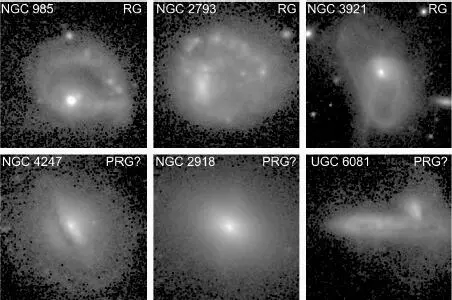

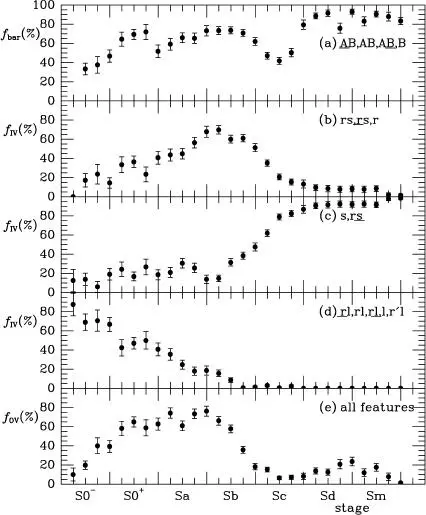

Figure 1.26shows the bar, inner variety and outer variety fractions ( fbar, fIV , and fOV , respectively) as a function of stage for subsets of EFIGI galaxies inclined ≤66°. The numbers are N = (a) 2,440, (b) 749, (c) 1,309, (d) 260 and (e) 2,642 galaxies. Figure 1.26(a)shows that the bar fraction has a minimum near stage Sc, with the highest bar fractions for extreme late-type spirals; Figure 1.26(b)shows that inner rings and well-defined inner pseudorings have the highest fraction around stage Sab; Figure 1.26(c)shows that (s) variety is uncommon for types Sab and earlier, but jumps to ≥80% for stages Sc and later; Figure 1.26(d)shows that lenses, ring-lenses and pseudoring-lenses are found mainly among stages Sb and earlier; and Figure 1.26(e)shows that outer features (rings, pseudorings, lenses and ring lenses) are most common between stages S0 +and Sb. Although outer features are rare for types later than Sb, Figure 1.26shows a secondary peak among extreme late-type spirals.

Figure 1.26. Systematics of CVRHS classifications from Buta (2019; EFIGI). The samples used for these graphs were restricted to inclinations ≤ 66 °

1.10.2. Astrophysical systematics

The CVRHS sequence of galaxy types from ellipticals to irregulars has astrophysical significance. This is because some measured properties of galaxies correlate with position along the sequence. For example, the integrated color index,  , ranges from ≈0.9 for E galaxies to ≈0.4 for magellanic irregular galaxies. Over the same range, the color index

, ranges from ≈0.9 for E galaxies to ≈0.4 for magellanic irregular galaxies. Over the same range, the color index  varies from ≈0.5 to −0.2. Color images of galaxies of different types available through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey show these differences directly. Types earlier than Sa tend to be yellowish, indicating the predominance of an old stellar population, while types Sc and later tend to be mostly bluish, indicating the predominance of a younger stellar population. Intermediate types (Sa to Sbc) show the presence of both populations, with bars and bulges usually yellowish and spiral arms generally bluish. As shown by Buta et al . (1994), the color indices of galaxies have a dependence on type that is well approximated by an integral Gaussian, showing little variation from type E to type S0 +, followed by a more rapid variation from type S0/a to types Sd and Sdm. This strong dependence on type, which carries into other colors such as

varies from ≈0.5 to −0.2. Color images of galaxies of different types available through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey show these differences directly. Types earlier than Sa tend to be yellowish, indicating the predominance of an old stellar population, while types Sc and later tend to be mostly bluish, indicating the predominance of a younger stellar population. Intermediate types (Sa to Sbc) show the presence of both populations, with bars and bulges usually yellowish and spiral arms generally bluish. As shown by Buta et al . (1994), the color indices of galaxies have a dependence on type that is well approximated by an integral Gaussian, showing little variation from type E to type S0 +, followed by a more rapid variation from type S0/a to types Sd and Sdm. This strong dependence on type, which carries into other colors such as  ,

,  and

and  (Buta and Williams 1995; Buta 1995a), has been interpreted in terms of a star formation history where the star formation rate declines exponentially with different decay rates (e.g. Kennicutt et al . 1994; Gusev et al . 2015).

(Buta and Williams 1995; Buta 1995a), has been interpreted in terms of a star formation history where the star formation rate declines exponentially with different decay rates (e.g. Kennicutt et al . 1994; Gusev et al . 2015).

Читать дальше

, ranges from ≈0.9 for E galaxies to ≈0.4 for magellanic irregular galaxies. Over the same range, the color index

, ranges from ≈0.9 for E galaxies to ≈0.4 for magellanic irregular galaxies. Over the same range, the color index  varies from ≈0.5 to −0.2. Color images of galaxies of different types available through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey show these differences directly. Types earlier than Sa tend to be yellowish, indicating the predominance of an old stellar population, while types Sc and later tend to be mostly bluish, indicating the predominance of a younger stellar population. Intermediate types (Sa to Sbc) show the presence of both populations, with bars and bulges usually yellowish and spiral arms generally bluish. As shown by Buta et al . (1994), the color indices of galaxies have a dependence on type that is well approximated by an integral Gaussian, showing little variation from type E to type S0 +, followed by a more rapid variation from type S0/a to types Sd and Sdm. This strong dependence on type, which carries into other colors such as

varies from ≈0.5 to −0.2. Color images of galaxies of different types available through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey show these differences directly. Types earlier than Sa tend to be yellowish, indicating the predominance of an old stellar population, while types Sc and later tend to be mostly bluish, indicating the predominance of a younger stellar population. Intermediate types (Sa to Sbc) show the presence of both populations, with bars and bulges usually yellowish and spiral arms generally bluish. As shown by Buta et al . (1994), the color indices of galaxies have a dependence on type that is well approximated by an integral Gaussian, showing little variation from type E to type S0 +, followed by a more rapid variation from type S0/a to types Sd and Sdm. This strong dependence on type, which carries into other colors such as  ,

,  and

and  (Buta and Williams 1995; Buta 1995a), has been interpreted in terms of a star formation history where the star formation rate declines exponentially with different decay rates (e.g. Kennicutt et al . 1994; Gusev et al . 2015).

(Buta and Williams 1995; Buta 1995a), has been interpreted in terms of a star formation history where the star formation rate declines exponentially with different decay rates (e.g. Kennicutt et al . 1994; Gusev et al . 2015).