1921–1937 THE FREE CITY OF DANZIG (1921–1937) A POGROM GERMAN-STYLE (SPRING 1937) PREPARING TO LEAVE DANZIG (SUMMER 1937) AT THE STATION (SEPTEMBER 1937) BERLIN (SEPTEMBER 2–12, 1937) Part II PARIS (SEPTEMBER 1937–SEPTEMBER 3, 1939) “THE PHONY WAR” (PARIS, SEPTEMBER 1939–JUNE 1940) THE DEBACLE (PARIS AND BAYONNE, JUNE 1940) TOULOUSE (JUNE AND JULY 1940) TO MARSEILLE, IN MARSEILLE (AUGUST–SEPTEMBER 1940) OVER THE PYRENEES (SEPTEMBER 11–13, 1940) WALTER BENJAMIN (LATE SEPTEMBER 1940) VILLA AIR-BEL (NOVEMBER 1940–FEBRUARY 1941) MAFIA (FEBRUARY–JUNE 1941) CHAGALL (SPRING 1941) MAX AND PEGGY DEPART (JULY 1941) THE EXPULSION OF FRY; MY MOUNTAIN CLIMBING ADVENTURE (AUGUST–DECEMBER 1941) GRENOBLE (DECEMBER 1941–AUGUST 26, 1942) Part III INTERNMENT (AUGUST 27–29, 1942) ESCAPE (SEPTEMBER 6, 1942) UNDERGROUND INTELLIGENCE AT MONTMEYRAN (AUTUMN 1942–MARCH 1943) MANNA FROM THE SKIES (NOVEMBER 1943–MAY 1944) LAST DAYS ON THE FARM (JUNE 1944) BECOMING A GUERRILLA (JUNE 1944) HAUTE CUISINE IN THE CAMP (JUNE–JULY 1944) THE AMBUSH (JULY 1944) THE 636TH TANK DESTROYER BATTALION (AUGUST–OCTOBER 1944) THE TELLER MINE INCIDENT (OCTOBER 11, 1944) HOMECOMING TO PARIS (DECEMBER 1944–FEBRUARY 15, 1945) GRANVILLE (FEBRUARY 15–MARCH 8, 1945) UNRRA (APRIL 1945–OCTOBER 1945) TO AMERICA (OCTOBER 1945–JULY 13, 1946) EPILOGUE: WHAT HAPPENED TO … PICTURE SECTION INDEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

AS I WRITE this memoir, I am almost one hundred years old—ninety-eight to be exact. The first two years of my life are the hardest to remember. Whenever I try, I hear my parents’ voices, see the contours of their faces, feel the softness of my crib. Everything else I know of my first years I picked up from stories my parents told friends and relatives about their smart son’s first steps and words.

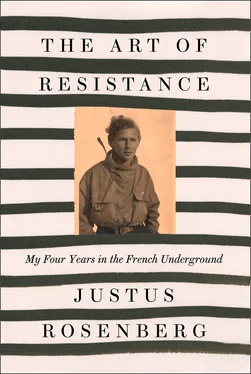

The only objective evidence of my early existence are two photos of an infant sitting on a bear rug, and a birth certificate issued by the Danzig registration office stating that on January 23, 1921, a boy named Justus Rosenberg was born to nineteen-year-old Bluma Solarski, wife of businessman Jacob Rosenberg, age twenty-three, both of the Mosaic faith, as Jewish people were commonly referred to at that time.

Unless you are a stamp collector or interested in the two world wars and the period between them, you’ve probably never heard of Danzig, a seaport on the Baltic, for generations a bone of contention between Germans and Poles. At the Versailles peace conference after World War I, to reward the Poles for having supported the Allies, the League of Nations decided to grant Poland the independence it had lost in 1796, when it was partitioned between Prussia, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Per the Treaty of Versailles, Danzig was to be part of Poland, even though 75 percent of its population was ethnically and culturally German.

Then, to the dissatisfaction of both the Poles and the Germans, on November 15, 1920, the League of Nations declared the disputed territory to be a semiautonomous city-state with its own flag, national anthem, currency, and a constitution patterned after the Weimar Republic. It was to be called “the Free City of Danzig” and to consist of the seaport itself and some two hundred towns and villages in the surrounding area. The League appointed a neutral high commissioner to the infant parliamentary democracy to ensure that the rights of the 20 percent of the population who were Poles and 5 percent who were Jews would be respected. As the name suggested, the Free City had no entrance restrictions. Between 1920 and 1925, in the midst of continuing European political unrest, ninety thousand Jews from Poland and Russia passed through Danzig en route to Canada and the United States. Another six thousand, satisfied with the city-state’s parliamentary democracy and liberal economic policies, or who identified with German culture, chose to remain. My parents, who had no intention of emigrating to America, were among these.

They had come from Mlawa, a Polish shtetl only a few miles from East Prussia, so they spoke German fluently and were familiar with German literature and music. Like most young people of their generation they knew hardly anything of Yiddish culture besides the language itself. My mother, the daughter of a tailor, and my father, born into one of the wealthiest and most learned Jewish families in Mlawa, fell in love when they were very young, and my father had just begun to work in his father’s business. Marriage was out of the question because they belonged to different social classes, so they eloped—to Danzig—and sought to become assimilated into German culture as quickly as possible. Immediately after my birth—which came not long after their elopement—they hired a nanny named Grete, who taught me traditional German children’s ditties, German fairy tales, and the rhymed verses of Struwwelpeter and Max and Moritz . At age six I entered the Volksschule (primary school). I already knew how to read and write both German and Gothic script.

For all practical purposes, I was educated like a typical German child—as was my sister, Lilian, six years my junior. Our parents rarely spoke Yiddish in our presence except when they were discussing something not meant for our ears. Somehow, I picked it up anyway. They celebrated Jewish holidays irregularly and only occasionally attended services at a “reformed” synagogue. Like most Jews in Germany, my parents considered themselves Germans “of the Mosaic persuasion.” They rejected political Zionism, which regarded Judaism as a nation. When I was ten years old, my mother enrolled me at the most prestigious gymnasium in Danzig, the Staatliche Oberrealschule. As was true of many young people in those years, the world of politics fascinated me. At the age of nine, I already dreamed of becoming a diplomat.

In the Danzig elections of 1932, the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (Nazis, for short) won the largest number of seats in the Volkskammer (people’s chamber), the legislative assembly. That gave them the right to appoint the “senate” (the executive branch), which until then had consisted of a coalition of liberal democrats, socialists, and moderate conservatives. However, the special nature of the Free City of Danzig, with its role as an international port and financial center, made the Danzig Nazis put a moderate face on their policies and ideology in spite of their victory, and this remained the case for the next five years.

There were, of course, pupils in my class who came to school dressed in Hitler Youth uniforms, but they rarely ostracized me or voiced their displeasure that I, a Jew, was always picked to recite (because of my perfect German diction) the ballads of Schiller or poems by Goethe and other classical poets; nor did they object to my being chosen for the school’s Schlagball team (a German form of baseball). The teachers remained strictly professional. For instance, even after 1932, I was the history teacher’s prize student. I also must have been the favorite of the director of the gymnasium choir, for he recommended me to participate in the all-boy angel-chorus of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion , at St. Mary’s Church in town. Thanks to him, I was also selected to sing in the children’s chorus of Bizet’s Carmen at the Danzig City Theater, a theater traditionally subsidized by the municipality that continued to be so under the Nazi government.

I owed my love of singing to my father. As soon as he came home from his office, he would sit down at our old upright piano, play and sing (by ear) popular arias from Italian operas, and invite me to join him, which I enjoyed doing until I developed a taste of my own in music.

Читать дальше