George concluded that land monopoly was to blame. It operated at two different levels of intensity. Speculation caused depressions by enabling people to demand prices which were extraordinarily high: effectively, the monopolists demanded a part of tomorrow's output today. The effect of this is to milk the returns to capital and/or labour. But this can only be tolerated up to a point, beyond which it becomes uneconomic to employ either capital or labour; unemployment ensues. Secondly, land monopoly enables speculators to hold land idle in the expectation of future capital gains. This is the wait-and-see strategy. As a result, scarce land is withheld from production in itself preventing new employment — and as a consequence of the contraction in supply, this pushes up the level of rents of land in use. This has the effect of bankrupting some firms which would otherwise be profitable and competitive.

Production [wrote Henry George] therefore, begins to stop. Not that there is necessarily or even probably, an absolute diminution in production; but that there is what in a progressive community would be equivalent to an absolute diminution of production in a stationary community — a failure in production to increase proportionately, owing to the failure of new increments of labour and capital to find employment at the accustomed rates. 5

This produces ‘a partial disjointing of production and exchange’, which manifests itself in apparent over-production and under-consumption. A decline in output continues until one or a combination of three things happens:

(1) the speculative advance in rents terminates;

(2) an increase in the efficiency of capital and/or labour results in an increase of income and a readjustment of the distribution in relative shares going to the factors of production; or

(3) labour and capital reconcile themselves to lower returns in wages and interest.

Henry George provided an account of how recessions cause the collapse of banks, the bankruptcy of firms and the panic of speculators who find that they have to finance loans at high interest rates for land which is suddenly seen to be over-valued. He used largely impressionistic evidence to support his theory. For this he cannot be criticised, for it is only in recent years that statisticians have produced data in anything like sufficient quantity and quality to enable us to elaborate the theory in a scientific manner.

Our first problem concerns periodicity. The waves in the trade cycle move in regular sequences. The shortest, terminating every four or five years, is the one which concerns democratic politicians most. They feel obliged to keep wary eyes on the economic indices in case these predict unfavourable events coinciding with election time. The most important cycle is of 20-year duration. The cyclical trends in the movement of phenomena like population, migration, immigration and house building were first fully elaborated by Simon Kuznets for the USA. 6 The importance of these long cycles is that they terminate in slumps, the amplitudes of which are greater than those experienced during the course of the upswing of the cycle. This is because inventory investment and other volatile forms of investment coincide with a downturn in the building programme, thereby creating a severe recession. 7 But Kuznets has admitted that, while there is no difficulty in identifying the long swings, there is a problem in explaining them. 8 He had to content himself largely with describing the phenomena.

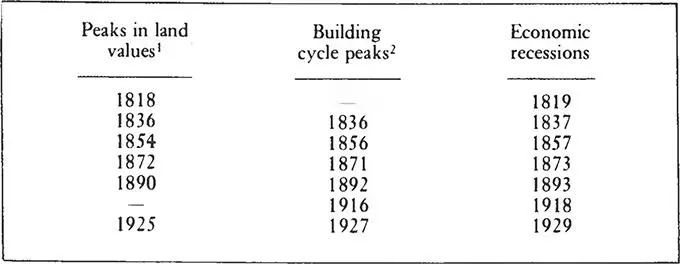

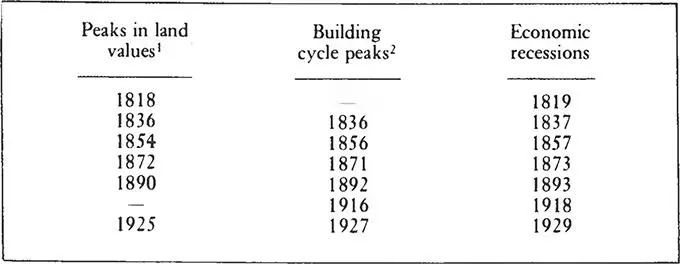

Does the land speculation hypothesis fit into the 20-year cycle? In the 1930s Homer Hoyt, then a post-graduate student at the University of Chicago, investigated the trends in land values in Chicago over the remarkably long period of 100 years. He discovered a regular cycle of 18-year duration. 9 His data is considered to represent the general trend in real estate values in the USA over the period up to the 1930s. 10 Hoyt has since up-dated his material, and his results are listed in Table 5:I. They fit neatly into the sequence of business cycles. A peak in land values is missing. Its absence may be explained by the threat and advent of the world war, which disturbed the benign psychological outlook which is necessary for speculation. Consequently, the peak of this cycle was eliminated. 11

But what if the trends in land values were simply a response to other variables in the economy? We expect to see a rise in land values, for as national income increases, so does the surplus, or economic rents. Rising land values, then, are a derived phenomenon. So how can we justifiably ascribe the primary power to cause recessions to the land market, the income for which is itself dependent upon the functioning of the labour and capital markets ? Is it not possible that a downturn in national income then results in a drop in land values ? This is the popular view: the causal forces are held to be in the opposite direction to the one postulated by Henry George. To prove a causal connection working from land speculation to the wider economy, we need to trace more than ‘a fairly close correspondence’ 12 between movements in the real estate market and phenomena like the building cycle.

TABLE 5:I

USA 1818-1929

Sources: 1 Homer Hoyt, ‘The Urban Real Estate Cycle - Performances and Prospects’, in Urban Land Institute Technical Bulletin No. 38, 1950, p. 7. 2 G. Shirk, ‘The 18?-Year Cycle in Total Construction’, Cycles , August 1981, p. 149, Figure 1, and C.A. Dauten and L. M. Valentine, Business Cycles and Forecasting , Ohio: South-Western Publishing Co., 1974, p.277. For the booms of the 1830s and 1850s, see also G. F. Warren and F. A. Pearson, World Prices and the Building industry , 1937, p. 99.

The timings favour Henry George’s hypothesis. Table 5:I shows that the peak in land values is reached 12 to 24 months before the economic recession; i.e., the downturn in land values precedes the decline in general economic prosperity. But this chronological sequence is insufficient to prove cause and effect. Landowners may just be blessed with better predictive foresight than the rest of us (though, in that case, why do so many of them continue to buy land just as the speculative bubble is about to burst?).

We need to demonstrate a transmission mechanism, one by which antecedent behaviour in the land market diffuses itself into the factory, office and corner retail store. One such mechanism may be the activity in the construction industry. If land, because of speculation, costs too much, does this curtail construction and thereby dampen activity over a wider sphere of the economy? The American evidence is tantalising. The peaks in the building cycle follow the peaks in land values and precede general economic recessions! This relationship will be investigated in detail in Chapters 8 to 10. First, however, we need a more detailed account of speculative behaviour.

Land speculation is a two-dimensional activity. It is spatial. It entails the acquisition of control over a clearly-defined piece of territory, such as land on the fringe of an urban area, or large tracts on the frontiers of a colonising society. It is also temporal. Purchases today are calculated to provide a financial gain through resale in the future. Thus, the dealer has to be willing and able to hold onto land for a period of time, and sell when he calculates that prices have reached their most attractive heights.

A useful definition of land speculation has been provided by Prof. Botha. It is, he says, ‘an investment over a relatively short period of time in an asset yielding an unrealistically high rate of return accompanied by a relatively low degree of risk’. 13 This contrasts land speculation with speculation in other areas, in which the risk of loss is much greater — for example, in the currency markets. We need to know more about the time scales, however, to see how they relate to the 18-year cycles that have been observed in the US economy.

Читать дальше